ehn

Biden finalizes long-awaited hydrogen tax credits ahead of Trump presidency

Responses to the new rules have been mixed, and environmental advocates worry that Trump could undermine them.

The Biden administration has finalized long-anticipated hydrogen tax credit rules just weeks before Trump takes office.

The rules, set by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service, will determine when hydrogen producers can claim substantial tax credits intended to incentivize the production of clean hydrogen energy.

The draft rules received over 30,000 comments from industry groups and environmental advocates alike that Treasury and the IRS spent the last two years interpreting. While concessions were made on both sides, the reception of the rule has been mixed and the rule could be subject to change under the Trump administration.

The Biden administration has pushed for clean hydrogen production to decarbonize heavy industries that are difficult to electrify, like trucking and steelmaking. Hydrogen is often more expensive to produce than traditional energy sources, so the tax credits were created to decrease costs for the producer and allow hydrogen to compete with traditional energy sources in foreign and domestic markets.

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

Hydrogen can be produced through a variety of methods with varying carbon emissions. Clean hydrogen is defined by the new rules as creating up to four kilograms of carbon emissions per every kilogram of hydrogen produced. Credit-eligible hydrogen production has two pathways, electricity or methane. Eligible electricity sources include renewables like solar and wind, but also nuclear. Additionally, hydrogen production from methane, whether using natural gas, steam reforming or coal mining, is also included with the addition of carbon capture technologies to reduce emissions.

The tax credit, which producers can claim for up to a decade, operates on a tiered system that rewards hydrogen producers with the lowest carbon intensity with the largest credit of $3 per kilogram and is scaled down to about 60 cents per kilogram. The program will expire on Jan. 1, 2033, meaning facilities must begin construction by this date if they wish to claim the credit.

Concessions and Changes

Reception of the final hydrogen rules have been mixed. In the 30,000 comments made on the draft rules, industry groups requested things like more pathways for natural gas and looser requirements for clean hydrogen production, while many environmentalists requested a heavier emphasis on renewable energy and strengthened emissions calculations.

Beyond the concerns about rules, many stakeholders have spoken out against federally-funded hydrogen development, citing a lack of transparency and lack of public involvement in the decision-making process.

Environmental groups have supported “three pillars” as safeguards for hydrogen production and lobbied for them to remain in the final rules: incrementality, temporal matching and deliverability. They’re complex, but they aim to ensure that hydrogen growth is from new, sustainable facilities (incremental), that hydrogen facilities can produce energy supply to meet a demand (temporal matching) and that hydrogen is reliably delivered (deliverability). These three pillars, in theory and supported by studies, should prevent imbalances that could inadvertently result in more carbon emissions than not producing hydrogen to begin with. These safeguards specifically apply to hydrogen using electricity, whether from renewables or nuclear sources.

While the principles of the three pillars did remain in the final rule, they did not go untouched.

“There have been a lot of concessions,” Matt Lifson, an attorney with the Institute for Policy Integrity at the NYU School of Law, told EHN. “The Treasury did give industry a bunch of things that it asked for.”

For example, Lifson said, there are some exceptions for existing nuclear facilities that will be allowed to claim the credits despite not being new sources of energy, and some rules are more lax in states like California or Washington due to their “robust greenhouse gas emission caps,” according to the Treasury.

“One of the [federal] hydrogen hubs is in California, [and] one of the hydrogen hubs is in the Pacific Northwest,” Lifson noted. “So that [exemption] will make it easier for those hubs…And going back to the nuclear issue, several of those hubs involve hydrogen made from nuclear energy.”

Other concessions included more flexible timelines and deadlines on production standards, which some hydrogen producers praised.

“The new hydrogen rules mark significant progress, with notable revisions,” Plug Power, a hydrogen fuel cell company said in a statement. “While these updates are encouraging, we look forward to collaborating with the new administration to refine the regulations.”

Will the rules hold under a Trump presidency?

Trump administration plans to overhaul Interior Department with budget cuts and policy reversalsCredit: palinchak/Big Stock Photo

Trump administration plans to overhaul Interior Department with budget cuts and policy reversalsCredit: palinchak/Big Stock PhotoIn a matter of days the Trump administration will have the ability to challenge the hydrogen rules under the Congressional Review Act.

“There's still the possibility that the rules could change under the Trump administration,” Lifson said. “So I don't know how much certainty we really have.”

There are a few factors that could prevent the rules from being invalidated. Amidst more pressing issues, hydrogen production might not make it onto Trump’s priority list for his first 100 days in office, and congressional review must be conducted within 60 days of a rule being published. Even if Trump does tackle the new rules on time, the process requires a majority vote, which could be difficult to achieve since the hydrogen credit rule has bipartisan support and the incoming Republican Congress will hold the majority on a thin margin.

“There is always a chance that this is an acceptable compromise between various segments of industry and the environmental community and that [the final rules] could hold,” Lifson said. “There's also the fact that if the Trump administration wanted to rewrite the regulations through its own rulemaking, they would need to rationally explain any departures that they made from the Biden rule. It can't just be a ‘because we said so’ type of thing.”

Peter Dykstra: The good news that gets buried by the bad

On the environment beat, maybe it’s right that the bad news dominates. But the good news is out there, too.

Habitat loss. Climate change and its impacts. Mass extinctions. Pollution and its impacts. Every once in a while, maybe it’s a good idea for someone like me to shut up and talk about the victories – even if they’re small. Here are but a few.

An endangered species law with teeth

Wow. Just wow. When a large animal recovers from near-extinction, it’s usually because they’re cute and cuddly, or otherwise adorable, and generate huge public support. American alligators aren’t adorable and cuddling is not recommended.

But there’s a market for alligator meat and hides. Men and women who proudly call themselves “swamp rats” so efficiently killed these beasts that their 1967 designation as an endangered species pre-dated the current Endangered Species Act by six years.

Alligators made a remarkable comeback and were taken off the endangered list in 1987. Today, tightly controlled gator hunting has resumed, and unless you have strong feelings against hunting gators, Louisiana expects a record hunt this year.

Coal’s continuing comedown

Last week a demolition crew took down the main building and towering smokestack of a coal-burning power plant near Boardman, Oregon. As a result, Oregon became the latest state to become completely free of coal-burning facilities.

This week, Hawaii is scheduled to shut its only coal plant, meeting the state deadline to quit coal by the end of 2022. One caveat: Hawaii will have to backslide for a while until clean energy makes a home there. It'll be the tenth state to shut down its coal-burning facilities.

Currently, oil and natural gas, shipped in from the mainland, are the only options until clean energy takes hold.

A coal consolation

The American Chestnut once covered hillsides all over the eastern U.S., but a blight nearly wiped out the tree in the mid-20th Century.

And as America’s coal industry receded, it left behind a mess of abandoned coalfields with barren, acidified soil.

Enter a nonprofit called Green Forests Work. They’ve planted thousands of chestnuts on minesites — It turns out that chestnut seedlings can thrive in thin, disturbed acidic soils. Since 2009, the group has planted “over tens of thousands of chestnuts, across 9,400 acres of mined lands,” according to the New York Times.

The minesites and the chestnuts are both a long way from salvation, but here’s one case where innovation and inspiration work together.

Giving away your entire company for climate action

Yvon Chouinard was a climate activist before climate was hot. At 83, the billionaire owner of the Patagonia brand of outdoor wear and gear may no longer be an everyday rock climber, but he’s making big changes with the company: He’s giving it away to fund climate action.

He’s fond of saying “Earth is now our only shareholder” of his $3 billion baby, now the property of the Patagonia Purpose Trusts and a new nonprofit, the Holdfast Collective.

Building back green after disaster

Two years ago, in the midst of the worst wildfire year in Oregon history, about half the town of Talent was wiped off the map.

Following the lead of other towns felled by floods, tornadoes and even a tsunami, Talent built back smarter.

Triple-pane windows and fire-resistant insulation are two of the improvements backed by Energy Trust, a utility-supported nonprofit that counsels homeowners on energy efficiency. The website Fast Company talked to one homeowner who said his monthly electric bill has shrunk to $11.

Talent has many post-disaster role models. In May 2007, Greensburg Kansas was destroyed by an EF-5 tornado. Homes and buildings were rebuilt with Insulated concrete form blocks that deal much better with heat, cold and destructive winds. The entire town now runs on 100% renewable energy and high speed fiberoptics.

Valmeyer in Ilinois, and Soldiers Grove in Winsonsin, are two river towns that suffered regular damage from major floods. With federal funding, they rebuilt uphill and out of harm’s way, Valmeyer in 1993 and Soldiers Grove the early 1980s.

Now Talent and other towns destroyed by fire can provide examples for future wildfires.

But by curbing climate change and other causes of so many “natural” disasters, it would be better news if we focused more on the ounce of prevention.

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist and can be reached at pdykstra@ehn.org or @pdykstra.

His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher Environmental Health Sciences.

The Titans of Plastic

Pennsylvania becomes the newest sacrifice zone for America’s plastic addiction.

Pennsylvania has become the newest sacrifice zone for America’s plastic addiction.

During the summer of 2018, two of the largest cranes in the world towered over the Ohio River. The bright-red monoliths were brought in by the multi-national oil and gas company Shell to build an approximately 800-acre petrochemical complex in Potter Township, Pennsylvania—a community of about 500 people. In the months that followed, the construction project would require remediating a brownfield, rerouting a highway, and constructing an office building, a laboratory, a fracked-gas power plant, and a rail system for more than 3,000 freight cars.

The purpose of Shell’s massive complex wasn’t simply to refine gas. It was to make plastic.

Five years after construction began at the site, Shell’s complex, which is one of the biggest state-of-the-art ethane cracker plants in the world, is set to open. An important component of gas and a byproduct of oil refinery operations, ethane is an odorless hydrocarbon that, when heated to an extremely high temperature to “crack” its molecules apart, produces ethylene; three reactors combine ethylene with catalysts to create polyethylene; and a 2,204-ton, 285-foot-tall “quench tower” cools down the cracked gas and removes pollutants. That final product is then turned into virgin plastic pellets. Estimates suggest that a plant the size of the Potter Township petrochemical complex would use ethane from as many as 1,000 fracking wells.

Shell ranks in the top 10 among the 90 companies that are responsible for two-thirds of historic greenhouse gas emissions. Its Potter Township cracker plant is expected to emit up to 2.25 million tons of climate-warming gases annually, equivalent to approximately 430,000 extra cars on the road. It will also emit 159 tons of particulate matter pollution, 522 tons of volatile organic compounds, and more than 40 tons of other hazardous air pollutants. Exposure to these emissions is linked to brain, liver, and kidney issues; cardiovascular and respiratory disease; miscarriages and birth defects; and childhood leukemia and cancer. Some residents fear that the plant could turn the region into a sacrifice zone: a new “Cancer Alley” in Beaver County, Pennsylvania.

“You have to drill the wells to support the petrochemical plant, but you also have to build the petrochemical plant in order to keep drilling the wells. It’s like a Ponzi scheme for natural gas.” – Rebecca Scott.

“I’m worried about what this means for our air, which is already very polluted, and for our drinking water,” said Terrie Baumgardner, a retired English professor and a member of the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community, the main local advocacy group that fought the plant. Baumgardner, who is also an outreach coordinator at the Philadelphia-based nonprofit environmental advocacy group Clean Air Council, lives near the ethane cracker. In addition to sharing an airshed with the plant, she is one of the approximately 5 million people whose drinking water comes from the Ohio River watershed. When Shell initially proposed the petrochemical plant in 2012, she and other community advocates tried their best to stop it.

And the plant’s negative impact will go far beyond Pennsylvania. Shell’s ethane cracker relies on a dense network of fracking wells, pipelines, and storage hubs. It’s one of the first US ethane crackers to be built outside the Gulf of Mexico, and one of five such facilities proposed throughout Appalachia’s Ohio River Valley, which stretches through parts of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. If the project is profitable, more like it will follow—dramatically expanding the global market for fossil fuels at a time when the planet is approaching the tipping point of the climate crisis.

For the residents who live nearby, Shell’s big bet on plastic represents a new chapter in the same story that’s plagued the region for decades: An extractive industry moves in, exports natural resources at a tremendous profit—most of which flow to outsiders—and leaves poverty, pollution, and illness in its wake. First came the loggers, oil barons, and coal tycoons. Then there were the steel magnates and the fracking moguls.

Now it’s the titans of plastic.

Jeff Bryant and his daughter, Cheyenne, live in Marianna, one of the most heavily fracked counties in Pennsylvania. Cheyenne tested positive for biomarkers of exposure to toxic chemicals.

Photos by Nate Smallwood for Environmental Health News and Sierra Magazine

Scenes from Aliquippa, a town six miles south of the Shell plant that’s likely to be affected by its pollution.

Shell's petrochemical complex produces poly-ethylene nurdles. They are pellets, about the size of a lentil, which are used to make many consumer products, including the single-use plastic packaging and bags that contribute to the global plastic crisis. Microplastics contain a mix of harmful chemicals and have been found in virtually every corner of Earth’s water and soil and in animals throughout the food web, including human bodies. Nurdles are what’s known as “primary microplastics”: plastics that were tiny to begin with, not broken down from larger pieces. An estimated 230,000 tons of nurdles wind up in oceans every year. They resemble tiny eggs, so fish are prone to eating them.

Shell has promised that its Pennsylvania plant won’t release nurdles into local waterways. “Polyethylene powder and pellets are not allowed to make their way into local waterways under any circumstances,” a Shell spokesperson said in an email, pointing to the company’s enrollment in a program sponsored by the American Chemistry Council and the Plastics Industry Association that aims to help plastics manufacturers achieve “zero plastic resin loss.”

That program has been around for more than 25 years, but as of 2016, nurdles were still the second-largest source of ocean micropollutants (after tire dust). Nurdles are easily lost or swept away by the wind during transport via trucks, barges, and trains. Shipping accidents have led to vast spills. Unlike oil, nurdles aren’t classified as a hazardous material, so most states don’t regulate them, and federal agencies aren’t obligated to clean up spills.

Many nearby residents, however, remain unconvinced by Shell’s officious assurances. “Sooner or later, they’re gonna have a big spill of those nurdles,” said Bob Schmetzer, who cofounded the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community. “It’s a matter of time . . . There are nurdles in the water anywhere those plants are.”

As the world increasingly turns toward renewable energy and strives to decarbonize, fossil fuel giants like Shell are trying to advance a new plastics boom to keep their ventures afloat—and it’s working. Plastics manufacturing is estimated to account for more than a third of the growth in oil demand by 2030 and nearly half by 2050—ahead of trucks, aviation, and shipping, according to the International Energy Agency.

Shell’s Pennsylvania plant relies on ethane from fracking wells, a sector that has recently benefited from Russia’s war on Ukraine. Prior to the war, the industry suffered from an oversupply of gas and consistently low prices, which created negative cash flows and large amounts of debt. More than 600 fracking companies and related industries in North America filed for bankruptcy between 2015 and 2022. As of 2019, Shell was one of the largest fracking leaseholders and producers over a nine-county area in the Appalachia Basin, primarily in Pennsylvania, operating more than 300 wells. The cracker plant will create additional demand from existing wells and is expected to prompt the drilling of new ones, all at a time when the war in Ukraine has caused a huge spike in gas prices and a windfall for companies like Shell.

It takes millions of gallons of water to frack for gas, which are typically withdrawn from local waterways or aquifers. The wastewater that comes back up to the surface contains radioactive elements and heavy metals, and it isn’t always disposed of safely. Chemicals known to be dangerous to the environment and human health, such as PFAS, are also used in the process.

The plastics and fracking industries, and all the pipelines and infrastructure associated with them, are major drivers of climate change. Recent studies show that methane emissions from fracking have been drastically undercounted because these analyses don’t account for leaks. Methane is about 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at driving global warming in the short term. In 2019, global atmospheric methane reached a 20-year high, with some researchers pointing to the US fracking boom as the culprit.

“The cracker is really only here because of local natural gas and subsidies offered to Shell. Of course it’s beneficial for the folks who get those jobs, but we shouldn’t just look at a small set of local outcomes when considering these things.” – Nick Muller.

Between direct emissions and methane leaks from the fracking industry, the US plastics industry emits greenhouse gases at the same rate as 116 coal-fired power plants, according to a report from the advocacy group Beyond Plastics. The same report says that if the global plastics industry were a country, it would be the world’s fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter.

“Even this one facility is not just one facility,” Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, a Pittsburgh-based collaborative of more than 50 regional and national environmental advocacy groups, said of Shell’s Potter Township project. “The ethane cracker itself is well down the production chain. It starts with fracking wells, then there are gathering lines, pipelines, and compressor stations, among other facilities. And after the cracker plant, there are downstream manufacturing processes to turn these plastic pellets into products. Every single part of that chain poses risks.”

“You have to drill the wells to support the petrochemical plant, but you also have to build the petrochemical plant in order to keep drilling the wells,” said Rebecca Scott, associate professor of environmental sociology at the University of Missouri. “It’s like a Ponzi scheme for natural gas.”

The Beaver county Marcellus Awareness Community spent years fighting an influx of fracking wells long before Shell proposed to build an ethane cracker plant nearby. Once it learned about the proposal, the community group then pivoted from opposing wells to trying to stop the ethane cracker. During the course of a seven-year campaign, it formed partnerships with local and national environmental and health advocacy groups, including the Breathe Project and its members, such as the Clean Air Council, and with researchers at local universities and water protectors from Native American tribes throughout the watershed. Together, they launched a comprehensive grassroots campaign against the cracker: They canvassed, filed petitions, appealed permit approvals, spoke at public hearings, and held protests.

The Clean Air Council’s efforts secured some concessions from Shell, including improved traffic mitigation, additional restrictions on noise and light during construction, fence-line air monitoring, and improved pollution controls during flaring (burning off excess natural gas). But in the end, they couldn’t stop the plant. “None of it did any good,” Baumgardner said. “In the last year, we’ve changed our organizing strategy. Now we’re doing air monitoring, noise monitoring, light monitoring, and getting ready to watch the water for plastic nurdles.”

The Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community group launched Eyes on Shell, which provides resources like emergency planning information in case of an accident at the site; instructions on where to obtain air monitors; contact information for relevant regulatory agencies, nonprofits, and research groups; and detailed instructions on how to document and report any unusual happenings at the plant. Their vigilance proved valuable before the plant even opened. In September 2021, members of the group and other residents noticed a sickly-sweet maple-syrup-like smell emanating from the site and notified regulatory agencies. The state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) issued Shell violations for “malodorous air contaminants,” and Shell identified the smell as coming from chlorotolyltriazole, a compound that, according to the company, formed when they applied a corrosion inhibitor and bleach to cooling units at the plant. In March 2022, a piece of faulty equipment resulted in the spill of 2,500 gallons of sulfuric acid at the site. Again, residents and activists learned of the problem when a number of them received notifications from a national alert system that there had been a sulfuric acid spill in the area. Although the alert didn’t specify the origin of the spill, it didn’t take much research on the part of local activists to determine that it had occurred at the cracker plant. Shell later stated that the spill was entirely contained and that none made its way into nearby water or soil, and no violations were issued.

“The plant wasn’t even opened up yet, and they were already getting violations for not being able to contain these chemicals inside the fence line,” Schmetzer said. “It was scary.”

Living near fracking wells or related infrastructure has been linked to everything from preterm births and high-risk pregnancies to asthma, migraines, skin disorders, and anxiety. “For leukemia and lymphoma, the current understanding is that it could show up as soon as three to five years after exposure, and within less than 10 years for sure,” said Dr. Cheng-Kuan Lin, a physician and former researcher at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Solid tumors like lung cancer could take 10 or 20 years. And other cancer types could take more than 30 years to show up.”

Lin was the lead author on three studies examining literature on the cancer risk associated with living near petrochemical facilities. A study of leukemia found that people who live near petrochemical complexes are 36 percent more likely to develop cancer than those who don’t. The risk is higher for certain types of leukemia. People living near petrochemical facilities are about 85 percent more likely to develop chronic lymphocytic leukemia compared with people not living near these facilities. The studies also found that those who live near petrochemical complexes are almost 20 percent more likely to develop lung cancer.

Lin noted that pollutants from these types of facilities might vary from country to country, but they all emit benzene, a known risk factor for leukemia. Shell’s Pennsylvania plant will emit numerous cancer-causing chemicals including benzene and formaldehyde. He also pointed out that some of the studies followed people for only a short period of time, so they likely didn’t capture the whole picture. “In general, the longer you trace these populations, the more cancers you’ll find,” he said.

Families living among the Marcellus Shale fracking fields fear what the proliferation of wells will mean for their health. Jeff Bryant and his nine-year-old daughter, Cheyenne, live in Marianna, a tiny borough in Washington County that is located about 60 miles south of Shell’s new plant and is one of the most heavily fracked counties in the state. Only 450 people live there, and 21.6 percent of them live in poverty (a rate that’s substantially higher than the national poverty rate of 11.4 percent). When drilling began in 2018 at dozens of new fracking wells surrounding the town, Cheyenne, who was five at the time, developed headaches, respiratory problems, and nosebleeds. “She’d wake up in the morning with her nose bleeding, then just bleed and bleed,” Bryant said.

The headaches were alarming too. Cheyenne would hold her head and cry, saying, “My head is stabbing.”

In 2019, Environmental Health News tested the air, water, and urine of Pennsylvania families who lived near fracking wells for contaminants. The investigation found biomarkers for harmful chemicals in the bodies of children living near fracking wells at levels up to 90 times higher than the national average. Cheyenne’s urine sample showed biomarkers indicating exposure to toluene, ethylbenzene, styrene, benzene, and other chemicals used in fracking, which are linked to respiratory, kidney, liver, circulatory, and nervous system problems; skin irritation; and increased cancer risk.

“She’s been poisoned,” Bryant said. “All she does is run around outside with her friends—there’s no reason these things should be in her body.”

Some studies have found that emissions from fracking wells tend to be highest during the drilling phase. Cheyenne’s health problems got better once drilling had been completed. But Bryant worries more wells are coming, and the family can’t afford to move.

Dwan B. Walker, the mayor of Aliquippa, feels that Shell didn’t consider the opinions of his constituents.

Nate Smallwood for Environmental Health News and Sierra Magazine

Residents of Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh, are about 35 miles away from Potter Township, but they could be just as impacted by Shell’s cracker plant. Home to massive industrial polluters like US Steel and PPG Industries, the county had air that was among the dirtiest in the nation before Shell’s ethane cracker arrived. Yet even though air and water pollution don’t respect geographical borders, residents outside Potter Township were given little say about the plant.

Julie DiCenzo, a retired medical writer, joined the citizens group Communities First–Sewickley Valley because of her concerns about both the cracker plant and the fracking wells that had received permits less than a mile from her home. She started attending town meetings in neighboring Economy Borough, where some fracking wells had already received permits and the shale gas drilling company had plans for more, but as a nonresident, she wasn’t permitted to speak. “Even though it’s in another county, it’s still affecting us,” DiCenzo said.

In addition to holding public educational meetings to raise awareness about the risks from the ethane cracker and fracking, members of Communities First–Sewickley Valley worked to persuade several of the 11 municipalities in the local school district to implement zoning ordinances that would keep oil and gas development as far away from residents as possible, with mixed success. This lack of political power for residents was evident in the permitting process for the Shell ethane cracker too. Residents of the counties surrounding the site regularly packed Potter Township’s community meetings about the plant, but some felt that their opinions didn’t count because they weren’t residents of the township itself.

The plastics plant has also raised concerns about environmental justice. Beaver County is 91 percent white, with a median household income of $59,000 a year and 9 percent of the people living below the poverty line. But within 15 miles of Shell’s plant, there are at least eight communities where residents are more than 30 percent non-white or more than 20 percent of people live in poverty. In Aliquippa, about six miles south of the plant, around 41 percent of the town’s approximately 9,200 residents are non-white and a third are Black. The median annual income is $36,451, and a quarter of its residents live below the poverty line.

When the plant was proposed, the promises to nearby residents were big: a 25-year operating contract, other new businesses in the region, and up to 20,000 direct and indirect jobs. But some Aliquippa residents say those promises remain unfulfilled. “The city hasn’t seen much benefit from the plant so far,” said Dwan B. Walker, who has served as Aliquippa’s mayor for 11 years. Being mayor of Aliquippa is a labor of love—Walker makes just $175 a month doing the job and works for a security company to pay the bills. He decided to run for mayor after his sister was shot and killed in 2009 because he wanted to make his community safer.

Walker, too, went to Shell’s public hearings about the plant but didn’t feel that his opinion or the opinions of his constituents mattered. He still hopes the plant might eventually create downstream manufacturing jobs for the residents of Aliquippa, but he also worries about his community’s and his own family’s health.

In 2021, following President Joe Biden’s executive order on environmental justice, Pennsylvania governor Tom Wolf formally established the Environmental Justice Advisory Board and the Environmental Justice Interagency Council. As it stands, Pennsylvania’s current policy states that environmental justice communities (defined as including “historically and currently low-income communities and communities of color”) should get extra consideration to review permits for polluting facilities. Aliquippa’s proximity to the plant means its air will be significantly impacted by emissions, but the town didn’t get such special consideration during the permitting phase. Nor did any of the other environmental justice communities nearby.

“It’s a weak policy,” said Joe Minott, the executive director and chief counsel for the Clean Air Council. Minott has criticized the DEP for declining to follow its existing environmental justice policies. “It contains very few specifics about how to actually achieve environmental justice, and it’s just a policy right now, not backed up by any regulations, so they’re not even obligated to follow it.”

In 2014, Minott’s group created a detailed report on the expected impacts of the ethane cracker, including increased risk of cancer and respiratory and heart disease, increased traffic, and light and noise pollution. The organization also provided expert witnesses and legal counsel to the community, then took Shell to court. Shell eventually settled on both counts and agreed to provide better pollution controls during flaring and continuous fence-line air monitoring at the plant, accompanied by a public online dashboard where residents can review air-monitoring data.

“They say ‘jobs, jobs, jobs,’ but a lot of legislators stop there in their critical thinking about the benefits of this kind of tax package.” – Sara Innamorato

Walker said residents of Aliquippa have also had concerns about fracking well proposals nearby. “The DEP didn’t hold any meetings with me or the city council to talk about environmental concerns,” he said. “We’d need to have a lot more conversations about that before we let it happen here. I don’t want to be in the grocery store hearing, ‘You let them do what?’ ”In an attempt to lure Shell to Pennsylvania, the state’s former Republican governor Tom Corbett approved legislation offering Shell an “unlimited tax credit” in 2012, one year after he slashed $1 billion in public education funding. It was one of the largest subsidy packages ever awarded to a company in the United States. Of the 183 state legislators who voted on the bill, just 62 voted against it.

That windfall hasn’t translated into growth for Beaver County. A study by the Ohio River Valley Institute, a nonprofit progressive research organization, concluded that during construction of the plant, Beaver County actually fell behind both the state and the nation in nearly every measure of economic activity. The county’s population has continued to decline, all while registering “zero growth in employment, zero reduction in poverty, and zero growth in businesses—even when factoring in all the temporary construction workers at this site.”

Other research promises that those benefits are still coming. A study commissioned by Shell and published by researchers at Robert Morris University in 2021 projected that once it opened, the ethane cracker would add nearly $4 billion a year to the state’s economy. In Beaver County alone, the report found, the complex would produce $260 million to $846 million in annual economic activity, including wages, benefits, and related spending. Environmental advocates called the report “propaganda” because it didn’t consider subsidies or externalized costs to health and the environment. The true costs and benefits remain to be seen.

It’s difficult to quantify the public health costs of a facility like the ethane cracker, but modeling tools offer a rough idea. According to predictions from the EPA’s CO-Benefits Risk Assessment tool, the plant’s emissions of PM2.5—toxic airborne particulate much tinier than the width of a human hair—are estimated to cost Beaver County an additional $16 million a year in health-care costs. That’s not counting other pollutants like volatile organic compounds and hazardous chemicals. Neighboring Allegheny County can expect about $13 million in additional health-care costs. The national health-care burden is expected to increase by about $70 million a year from pollution that travels from Shell’s plant beyond the area. A DEP spokesperson said that estimating potential health-care costs associated with emissions for a proposed facility is not part of the state’s permitting process.

Republican state senator Elder Vogel Jr., one of the sponsors of the $1.7 billion subsidy the state offered Shell, represents parts of Pennsylvania’s Beaver, Lawrence, and Butler Counties, including Potter Township, where the cracker plant is located. Despite the local opposition, he remains a firm supporter of the facility. “All across the world, people have heard about Beaver County now,” Vogel said. “This Shell plant is putting us on the map.”

When asked whether state legislators considered the public health costs before offering Shell $1.7 billion in tax subsidies, Vogel said, “No, not really. I don’t believe so.”

Nick Muller, a professor of economics, engineering, and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, coauthored a 2019 study on the environmental and employment impacts of the shale gas boom. It found that the adverse effects on public health almost exactly equaled the economic benefits, and the climate costs subtracted another $12 billion to $15 billion in value, putting the industry’s cumulative economic impact in the red. “The cracker is really only here because of local natural gas and subsidies offered to Shell,” Muller said. “Of course it’s beneficial for the folks who get those jobs, but we shouldn’t just look at a small set of local outcomes when considering these things.”

When having an abundance of natural resources either doesn’t translate into sustainable wealth or leaves a region more impoverished than it started, sociologists refer to it as “the resource curse.”

In Appalachia, examples of the resource curse abound, according to the University of Missouri’s Rebecca Scott. “Appalachia has been culturally marginalized by narratives of backwardness and welfare dependency, like the image of the hillbilly in popular culture,” Scott said. Those harmful stereotypes can make residents more eager to belong in ways that are seen as culturally important, like contributing to the production of energy or essential materials like steel and plastic. “It becomes not only about the community’s ability to have commodities but also its ability to belong, and for its members to have a sense of personal worth.”

This context helps explain why for some Western Pennsylvanians, the Shell plant felt like a godsend. “The Shell construction project put everybody in the unionized construction industry in Beaver County, Allegheny County, and Butler County to work, and then, because of the magnitude of the job, they started pulling in people from farther away,” said Larry Nelson, president of the Beaver County Building and Construction Trades.

Nelson’s organization, which is one of several local chapters of North America’s Building Trades Unions, represents about 20 local construction unions including plumbers, plasterers, painters, sheet metal workers, boilermakers, operating engineers, cement masons, and bricklayers. “Before that job started, just about all the trades had some form of unemployment,” Nelson said. “It helped the unions out greatly.”

Union members receive the same pay and benefits as others in their same profession, regardless of the type of job they’re working on or which client they’re working for, Nelson said. But the Shell project stood out as being one of the safest job sites he’s ever seen. “Workers had something called ‘work stop authority,’ which gives any worker the ability to stand up and say, ‘Wait, something doesn’t look safe. Let’s pause and take another look,’ ” he said. Nelson believes the plant could be a continuing source of employment and that Shell will call on the unions for future projects at the plant as needed.

Shell officials have made numerous efforts to demonstrate that the company makes a good neighbor. Shell gave $1 million to the Community College of Beaver County to develop a training program for petrochemical facility workers and has hired at least 13 graduates to fill permanent roles at the plant, according to a company spokesman. The company created a community advisory panel and hosts a quarterly virtual community meeting. During the pandemic, Shell donated money and services to local food banks and charitable organizations, donated hand sanitizer to local schools, donated N95 masks and nitrile gloves to local hospitals, and sponsored an employee donation drive for the Beaver County Humane Society.

“The community has benefited from the first day they started moving dirt down at the facility,” Vogel said. In addition to the jobs at the plant, the state senator pointed to the indirect jobs it has created, including those in the new hotels, restaurants, and facilities serving the influx of construction workers from out of town, and in the catering and shuttle services for employees at the site. “One of my neighbors is retired, but he got a job driving workers in from the off-site parking lots a few hours a week,” Vogel said. “Another neighbor up over the hill from me went to Shell’s new training program at the community college and got hired. He’s 21 or 22, and he’ll have a lifetime career there if he wants it.”

The political climate in Pennsylvania’s state government is aggressively pro-oil, pro-gas, and pro-industry. That’s driven in part by the Republican-controlled legislature, but Governor Wolf and other state Democrats have also supported the Shell project.

State representative Sara Innamorato, who represents parts of Pittsburgh, is one of the few Democrats who opposed the plant. “They say ‘jobs, jobs, jobs,’ but a lot of legislators stop there in their critical thinking about the benefits of this kind of tax package,” she said. “We aren’t doing the math to figure out this is costing us millions of tax dollars per job. We’re foregoing billions of dollars of revenue over the life of this plant at a time when we can’t afford to make necessary investments in our infrastructure, our public schools, or our small businesses.”

Bob Schmetzer spent nearly four decades working as an electrician with the local union. He supports good jobs for union workers. For him, Shell’s promises ring hollow.

“I lived through the era when the steel mills all shut down at one time,” he said. “I’m afraid we’re facing that again now. What happens when you take 8,000 temporary workers and they all leave or they’re all out of work again?”

For people like Schmetzer, who are living in the shadow of the cracker but not directly benefiting from the jobs, the trade-offs are obvious. His wife died from heart disease a few years ago, which he attributes in part to air pollution from the oil and gas industry and the proliferation of fracking wells. “She already had heart problems, so it wasn’t like air pollution originated it, but it kicked it into gear, and I’m still furious about that,” he said.

Following his wife’s death, Schmetzer’s sister, who lived nearby, fled the region when a fracking well went in about a mile from her house. She moved to North Carolina to get away from the well. “I don’t get to see my sister anymore,” he said. “I’m sure someone else would feel the same way if these things happened to their families.”

Many others, like Jeff and Cheyenne Bryant, can’t afford to move away. For the Bryant family, the stakes of Shell’s big bet on plastic couldn’t be higher—for Cheyenne in particular. “Twenty years of research on this fracking thing has already proven that it’s bad for our health,” Bryant said. “But they’re still putting in more and more wells that are killing us. It isn’t right.”

Editor's note: This story was produced in partnership with Sierra Magazine.

Peter Dykstra: Forty years of “just around the corner”

And now that electric vehicles may really be ready, a few new things to think about.

We’re seeing some big signs that electric vehicles (EV) may be ending their decades-long tease.

Here in Georgia, Republican Governor Brian Kemp is on the verge of landing two blockbuster electric vehicle production plants. Yes, a Republican with a track record of indifference on climate and environment.

Kemp faces a tough reelection bid in November against Stacey Abrams, and EV’s might help win that race. He’s cut a deal with Hyundai to base the Korean automaker’s EV manufacturing near Savannah. Hyundai plans to drop $5.5 billion into a complex with 8,100 jobs. In late 2021, Kemp closed a deal with California-based Rivian to build a $5 billion electric truck plant 40 miles east of Atlanta, promising more than 7,000 jobs.

The accelerated push for EV’s is not a Georgia thing. It is happening across the country.

Last month, California announced it will outlaw the sale of new fossil-fuel-powered cars starting in 2035. As many as a dozen other states are expected to follow suit.

GM has announced a not-nearly-big-enough network of 5,000 fast-charging EV stations to be located at truck stops and along interstates.

And last month’s unprecedented federal climate-healthcare legislation is an unmistakable sign that, for now, Washington is taking climate action seriously.

But…

The electronics revolution needed to support the EV revolution will create its own industries, many keying on the rare elements capable of powering advanced batteries.

There’s bit of a problem with this, though. Most of the fifteen elements that are considered to be rare earths – lanthanum, cerium and their 13 neighbors who reside in a rarely-visited neighborhood on the Periodic Table – can often be found in nodules on the sea floor or beneath the melting landscape of Greenland.

Marine scientists, and the environmentalists that have waged a 40-year fight to block or limit seabed mining for not-so-rare elements like manganese, cobalt and copper, are concerned that disruptive activity on the sea floor could harm sea life throughout the water column, and from top to bottom on the food chain.

Exploration firms assure that their activity will cause no harm. Since seabed mining is still just a concept, neither side can offer proof for their claims.

Yet, in August, a U.N. effort to establish standards for any seabed mining for rare earths failed.

The Pacific island nation of Nauru has served notice that they may start mining next year, setting off twin competitions for environmental damage and security tensions. China, with its huge electronics industry, currently leads in rare earth use, but the U.S. and others would love to catch up.Of course, I’m being more than a tad whiny. The potential risks of accessing rare elements are in no way a reason to shun EV’s.

The need to wean ourselves from our oil habit is a life-or-death thing. There are other ways that EV’s aren’t ideal. Juicing up your clean car on power that comes from a coal plant isn’t helping anyone.

But the news is overly good for those who seek an end to humanity’s fossil fuel era.

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist and can be reached at pdykstra@ehn.org or @pdykstra.

His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher Environmental Health Sciences.

Peter Dykstra: Headwinds remain for clean energy

Will the Inflation Reduction Act mark the time when fossil fuels begin to fossilize?

"What is good for the country is good for General Motors, and what's good for General Motors is good for the country."

Charles Wilson, 1953

As President Biden turns his victory lap for squeaking a major climate victory through a 50-50 Senate, the ghost of Charles Wilson remains. Wilson was the first defense secretary in the Eisenhower administration. And yes, he was a bit partial to GM because his previous job was CEO of the company.

If on top of Wilson’s ghost you throw in Big Oil and its dominance in U.S. foreign policy — witness Biden’s making nice with the Saudis last month — you’ll see the tricky road ahead to realize the promises of the Inflation Reduction Act.

To be sure, the climate and energy provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act are significant, even if they’re long overdue. But in order to placate the fossilized wing of the Democratic Party, for example, the bill broadens industry access to federal lands — even if the industry holds over 9,000 public lands drilling permits it hasn’t used.

These are some examples of the type of tactics that could jeopardize the implementation of the law.

Bumpy roads remain for electric vehicles

The 2006 documentary Who Killed the Electric Car?details successful efforts to engineer GM’s EV-1 out of existence in the late 1990’s. The EV-1 was praised by engineers. For all the world, it looked like an electric passenger vehicle was finally ready. Within six years, not only was the EV-1 program shut down, but the existing cars were destroyed, leaving virtually no trace.

The push of the fossil fuel industry against electric vehicles (EV) didn’t stop with the destruction of GM’s EV-1 program. Two years ago, the American Petroleum Institute spearheaded the launch of the Transportation Fairness Alliance, as brazen a front group as any. The group argues that gasoline or diesel-driven vehicle owners pay fuel taxes at the pump. EV owners, they reason, cheat the system by not pitching into the tax pool that funds road construction and repair. (In all fairness, EVs also don’t contribute to ground-level ozone pollution or “smog.” And, depending on the source of the electricity, EVs ideally don’t spew carbon into the air.)

However, investigators at DeSmog found that “the coalition is being managed by FTI Consulting, a DC-based international consultancy firm that has a long history of running front groups and PR campaigns for the oil and gas industry.”

Rooftop solar under attack

A report last year by the NGO Environment America detailed efforts by state-level agencies and “astroturf” grassroots groups to strip homeowners of the financial incentives for installing rooftop solar arrays. States including Ohio, Illinois, California, Kansas, South Carolina and Florida – ironically, “the Sunshine State,” – have seen years-long efforts to roll back utility paybacks to solar owners who sell their excess power back to the grid.

“Fredo” Koch and the wind farm

Bill Koch is the estranged brother of Charles and the late David Koch, the politically active dynamos that have bankrolled many far right causes since the 1980’s.

Bill is an avid sailor who won the 1992 America’s Cup. While his Oxbow Industries had nowhere near the multi-billion fossil fuel portfolio of his brothers, Bill had quite a pocketful of his own. He also had strong feelings about wind power competing with oil and potentially spoiling the view in Nantucket Sound from his Cape Cod home.

He poured millions into a group battling Cape Wind, a 24-square-mile, 130-turbine proposal for the Sound. Cape Wind developer Jim Gordon won approval from multiple state and federal agencies and endured at least 26 lawsuits before quitting in 2017.

What’s the moral in all this?

After decades of false starts and dashed hopes, wind and solar are beginning to turn in the numbers: Both grew at record rates in 2021. With science, economics, the increasing urgency of addressing climate change and a huge federal boost at their backs, is it really time for fossil fuels to begin to fossilize?

Billion-dollar businesses don’t go down without a fight. Ever.

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist. His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher Environmental Health Sciences.

How Colorado is preventing PFAS contamination from the oil and gas industry

And how other states, including Pennsylvania, could do the same.

Editor’s note: This story is a follow-up to our recent report that found PFAS in a private well near fracking in Pennsylvania.

PITTSBURGH—In June, Colorado became the first state to ban the use of PFAS during oil and gas extraction — and now, in light of recent research finding the potential for widespread contamination, some are calling for a similar ban in Pennsylvania.

Last year it was revealed that PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), a group of more than 9,000 chemicals, have been used in oil and gas wells for decades. The chemicals, which are water- and grease-repellent, are sometimes used in fracking fluid to make the chemical mixture more stable and efficient in flushing oil and gas out of the ground at high pressure. PFAS may also be used during initial drilling and other phases of oil and gas extraction — not just fracking.

That’s about to change in Colorado: A new bill restricts PFAS in products like carpets and furniture, fabric treatments, cosmetics, food packaging and children’s products; and bars the use of PFAS in any type of oil and gas extraction, including fracking. The law will take effect on Jan. 1, 2024.

With a separate, related bill, Colorado also became the first state to require oil and gas companies to publicly disclose the complete list of chemicals used “downhole” for all types of wells, and to certify that no PFAS were used during drilling or extraction.

Downhole chemicals include those used during drilling and other phases of operations. Most public disclosure laws in other states focus mainly on chemicals used in fracking wells, and most only require disclosure of chemicals used during extraction, ignoring the chemicals used during drilling or other operations.

“Prior to this legislation, there was a lot of secrecy involved in the chemicals being used downhole in oil and gas production operations,” Ramesh Bhatt, who advocated for the bill’s passage as chair of the conservation committee of the Colorado Sierra Club, told EHN.

Some scientists and health advocates think other states with a heavy oil and gas industry presence, including Pennsylvania, should do the same.

“When you’re talking about chemicals as toxic and persistent as PFAS, it’s extraordinarily risky to allow them in oil and gas extraction,” Dusty Horwitt, an environmental health consultant who testified before Colorado lawmakers considering the drilling disclosure law, told EHN.

Earlier this year, a group of researchers tested Washington County, Pennsylvania, resident Bryan Latkanich’s water for PFAS and detected seven of the chemicals, including several at levels well above the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended thresholds. Latkanich formerly had two fracking wells drilled about 400 feet from his home.

Carla Ng, a researcher who studies PFAS at the University of Pittsburgh and conducted the tests that found PFAS in Latkanich’s water, told EHN, “It’s very difficult to control where those chemicals go when drillers are pushing fluid into the Earth’s subsurface. Because of how harmful and persistent PFAS are, they should not be used in cases where their spread cannot be controlled.”

Critical gaps in state laws

A new Shell ethane cracker in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, which is expected to create additional demand for fracking wells.

Credit: Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance, 2021

The use of PFAS in oil and gas wells is likely creating an under-appreciated source of PFAS contamination, adding to Americans’ exposure to these harmful chemicals through food, personal care products and drinking water. But lack of transparency makes it difficult to assess how widespread the problem is.

“It’s impossible to know at this point,” said Horwitt, who also consults for the environmental health advocacy group Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Horwitt was lead author on a report published this month that found that in 16 leading oil- and gas-producing states, manufacturers of the chemical mixtures used in oil and gas extraction are generally not required to disclose complete lists of the substances they use.

The report also found that a number of states, including Pennsylvania, have laws that waive liability for oil and gas companies that don’t disclose complete lists of ingredients to regulators — as they’re required to by law — if they never received complete lists from chemical manufacturers.

Pennsylvania’s law also says chemical manufacturers can’t be held responsible for failing to disclose complete lists of ingredients in these products.

“So they’re all just off the hook,” Horwitt said.

The potential use of PFAS during drilling and other downhole operations is especially troubling, Horwitt said, because operators typically bore straight through groundwater, long before any casing or cement has been added to seal it off.

Further complicating things, some states, including Pennsylvania, have different disclosure requirements for conventional and unconventional wells. Operators of fracking wells have to publicly disclose chemicals used in their wells (minus any “trade secrets”), but for conventional wells, the public can only access that information through requests to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

Colorado closes the gaps

\u201cGreat News! I'm thrilled to share that the PFAs Bill HB22-1345 was signed into law today by @GovofCO. Thank you @GovofCO. A Big Thank You to @Cutter4Colorado for her leadership. Also, Thanks to Senate sponsors @PeteLeeColorado @SenadoraJulie #ClimateAction #BanPFAs #ClimateAction\u201d— Madhvi4EcoEthics (@Madhvi4EcoEthics) 1654275012

In recent years, Colorado has enacted some of the most health-protective oil and gas regulations in the country. The two new PFAS bills will further advance those protections.

“We have the most advanced timeline for banning these chemicals,” Josh Kuhn, the water policy manager for Conservation Colorado, one of the organizations that advocated for the legislation, told EHN. “This is a national leading policy.”

The bill was initiated after an 11-year-old girl named Madhvi Chittoor met with Colorado state Representative Lisa Cutter in the summer of 2021 to discuss PFAS contamination.

“When all of our aquifers are polluted, where will we get our drinking water from?” Chittoor asked. “When our waterways like ponds, lakes, rivers are polluted, where will the fish live? What water will the animals drink? What water will the farmers use to grow our crops?”

Cutter, a Democrat, was moved by Chittoor’s testimony and started working with groups like Earthjustice, the Sierra Club, and Conservation Colorado to craft the PFAS bill.

Many other states have passed bills restricting the use of PFAS in certain products, but none have addressed the use of PFAS by the oil and gas industry.

Kuhn said the effort to include the oil and gas industry in the state’s PFAS ban started after Physicians for Social Responsibility published a report in January 2022 that found PFAS were used in at least 10 Colorado counties. A subsequent analysis by the advocacy group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) found that Colorado had the most potentially PFAS-contaminated sites of any state, 86% of which were associated with the oil and gas industry.

Mary Bradford, a Republican member of the Colorado state House who cosponsored Colorado’s main PFAS bill, said she was mainly concerned about the health effects of PFAS on children and in consumer products.

“Now that we believe that PFAS is a potential health risk, we could be very surprised about how many products intentionally contain the PFAS compounds,” she said in a statement. Bradford’s district has experienced PFAS contamination of drinking water and well-documented PFAS exposures in people from a nearby military base.

“Chemicals that can harm people’s health are not just a one party issue,” Kuhn said.

While the bill banning PFAS didn’t have unanimous support, Kuhn said, they got more pushback against the consumer products portions of the bill than the oil and gas portion. The advocates and legislators working to get the bill passed talked directly with representatives from the oil and gas industry, which led to provisions that would allow for the use of PFAS in certain parts of oil and gas operations where they’re essential and good alternatives don’t exist — in gaskets and other pieces of equipment, for example.

Advocates like Kuhn and his colleagues also partnered with water utilities, which helped build bipartisan support.

“Water utilities on the receiving end of polluted water face significant challenges when it comes to removing PFAS,” Kuhn said.

Physicians for Social Responsibility’s reports cited evidence that PFAS may be used during the drilling phase for fracking and other types of oil and gas wells, but because no states currently require public disclosure of the chemicals used during drilling (as opposed to chemicals used during extraction), it’s impossible to know how common the practice is.

Colorado has found a solution to that with the separate bill that requires disclosure of downhole chemicals and requires that both operators and chemical manufacturers certify that no PFAS have been used.

“The first bill bans the use of PFAS by the oil and gas industry, and the second bill creates accountability,” Kuhn said.

There are a number of downhole operations, including drilling, that are different from what’s technically called fracking, Bhatt, with the Sierra Club, explained. Those chemicals are overlooked in most state laws.

Initially, the bill required complete disclosure of the ingredients used and their proportions, but after pushback from the industry related to revealing trade secrets, it was amended to require a complete list of individual chemicals used in oil and gas operations, but not their proportions or the exact mixtures used in specific products.

“You have to weigh the importance of protecting trade secrets against the importance of protecting health and the environment,” Bhatt said, “but we think this was a good compromise.”

Representatives from the American Petroleum Institute and the Colorado Oil and Gas Institute responded to the report by Physicians for Social Responsibility on the use of PFAS in oil and gas extraction last year, saying they agreed that PFAS shouldn’t be intentionally used in fracking fluid, and contesting the idea that trade secrets provisions could be hiding extensive PFAS use.

The American Petroleum Institute has also said that PFAS use in oil and gas wells is limited and that the trade group will continue to review available data to protect health and safety.

Possibilities for Pennsylvania

Several advocacy groups, including PennFuture, the Clean Air Council and the Environmental Health Project, have called for action on the issue of potential PFAS contamination from the oil and gas industry in Pennsylvania.

Kuhn and Bhatt said they haven’t heard much from lawmakers or advocates in Pennsylvania or other states about crafting similar legislation yet, but that they’d be happy to consult about how they’ve successfully regulated PFAS in Colorado. Kuhn suggested reaching out for resources to Safer States, an environmental health advocacy group that tracks legislation related to chemical safety throughout the states..

Kuhn also cautioned that while the bill was being crafted, advocates and lawmakers were pressured by some chemical industry groups to limit the specific PFAS they were restricting, which they did not do, and emphasized that a comprehensive ban on the chemicals is the most protective option.

“In Colorado,” he said, “no longer will any of these ‘forever chemicals’ be inserted into the ground, potentially threatening water supplies needed by both humans and wildlife.”

See part 1, PFAS: The latest toxic concern for those near fracking

PFAS: The latest toxic concern for those near fracking

The “forever chemicals” are used by the oil and gas industry, but a lack of transparency and accountability makes it impossible to know how widespread contamination could be.

PITTSBURGH—For more than a decade, Bryan Latkanich has discussed his concerns about fracking chemicals contaminating the water and air near his home with anyone who would listen.

Latkanich is a resident of Washington County, Pennsylvania, one of the state’s most heavily fracked regions. In 2020, an Environmental Health Newsinvestigation found evidence that Latkanich and his son Ryan had been exposed to harmful chemicals like benzene, toluene and styrene.

Now, researchers have uncovered more harmful substances in Latkanich’s tap water —“forever chemicals.”

Last year it was revealed that these chemicals, collectively referred to as PFAS (per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances), have been used in U.S. oil and gas wells for decades. As far as the experts we spoke with know, this is the first time PFAS that may be linked to fracking have been detected in household drinking water.

The chemicals don’t break down naturally, so they linger in the environment and human bodies. Exposure is linked to health problems including kidney and testicular cancer, liver and thyroid problems, reproductive problems, lowered vaccine efficacy in children and increased risk of birth defects, among others.

Latkanich’s water smells strange and tastes bad, and his son Ryan has emerged from the bathtub or shower with sores on his skin. Latkanich and Ryan have both had a host of ongoing health issues over the last decade, including stomach problems, asthma attacks, rashes and eye irritation; and for Bryan, repeated hospitalization for kidney issues.

“I’m wondering what this stuff does to your joints and your heart, and how it affects everything else I’m feeling,” Bryan told EHN. “My kidneys are already shot. I just want these people to stop. They gotta stop poisoning people.”

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh recently tested water samples from multiple taps at the Latkanich home. They detected seven of the 14 PFAS they tested for.

“What’s scary is that they didn’t just find one, they found a bunch of PFAS,” Latkanich said. “They don’t even have guidelines on some of these yet.”

Bryan Latkanich in his kitchen in Washington County, PA.

Credit: Connor Mulvaney/EHN

The chemicals, which are extremely water-repellent, are sometimes used in fracking fluid to make the chemical mixture more stable and to more efficiently flush oil and gas out of the ground at high pressure. There’s also evidence that the chemicals are used during initial drilling and other phases of oil and gas extraction, but companies aren’t required to disclose those chemicals, so there’s no way of knowing how widespread the practice is.

The new findings suggest PFAS contamination may represent yet another problem left in the wake of fracking. But a lack of transparency in the industry makes it impossible to track where the chemicals have been used. And secrecy about ingredients throughout the supply chain for drilling and fracking chemicals make it difficult to hold any one company accountable for PFAS contamination in drinking water, leaving people like Latkanich — and regulators and scientists — in the dark.

“It’s very difficult to conduct scientifically rigorous tests on an industry that operates with so much secrecy,” Dusty Horwitt, a consultant with the environmental health advocacy group Physicians for Social Responsibility, told EHN. Horwitt was a co-author of the report that initially uncovered the use of PFAS in fracking wells.

The PFAS in Latkanich’s water have national implications. Physicians for Social Responsibility’s report found evidence that oil and gas companies, including Chevron and Exxon Mobile, have used PFAS, or substances that could degrade into PFAS, in more than 1,200 fracking wells in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Texas and Wyoming. They also noted that PFAS could have been used in additional states and in additional types of wells.

A 2021 investigation by the Philadelphia Inquirer found evidence that PFAS had been used in at least eight oil and gas wells in Pennsylvania, but the state’s PFAS action team has not publicly addressed the issue of PFAS in the state’s oil and gas wells, and did not respond to questions about whether it is assessing the potential for widespread PFAS contamination from oil and gas wells.

This is especially troubling for people using private drinking water wells like Latkanich, who tend to live in rural areas where oil and gas extraction takes place. An estimated 43 million Americans use private wells, which are not protected by the federal Safe Water Drinking Act and aren’t regulated in most states, so the water isn’t routinely tested or monitored, and the responsibility for cleaning up dangerous chemicals falls to homeowners.

“Considering how toxic and persistent these chemicals are, and the evidence that they have been used in oil and gas extraction for decades,” Horwitt said, “it’s critical for state regulators to start looking for these contaminants in people’s drinking water near oil and gas sites.”

Exceeding health thresholds

Bryan and Ryan Latkanich in front of their home in Washington County, PA

Credit: Connor Mulvaney/EHN

Carla Ng, a researcher who studies PFAS at the University of Pittsburgh and who supervised Latkanich’s water tests, said it’s possible the contamination came from the fracking wells that were previously drilled and operated 400 feet from Latkanich’s home, but there’s no way to know for sure.

“It’s really frustrating that we don’t know exactly what chemicals were used [in the wells], so we don’t even know exactly what to test for,” she told EHN.

In the absence of that information, Ng tested for 14 common PFAS. They detected seven compounds in one or more of the water samples from Latkanich’s home:

- PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid)

- PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid)

- PFHpA (Perfluoroheptanoic acid)

- PFNA (Perfluorononanoic acid)

- PFDA (Perfluorodecanoic acid)

- PFDS (Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid)

- PFHxS (Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid)

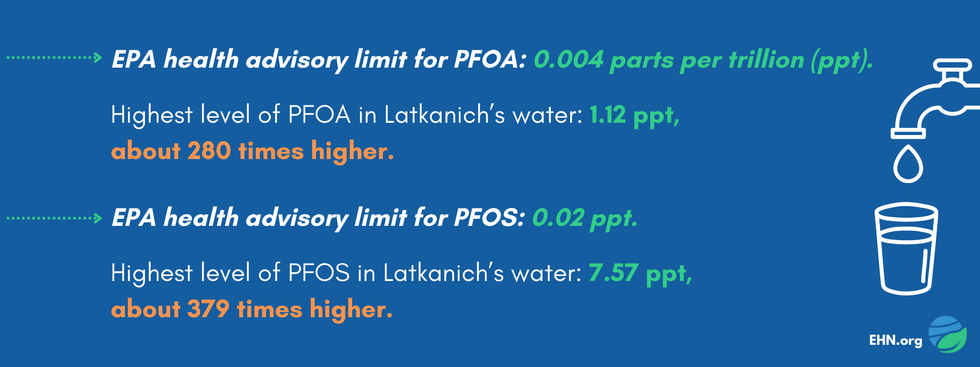

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently set new health advisory limits for a handful of the most well-studied PFAS including PFOA and PFOS. Health advisory limits are not enforceable regulations, but are recommended limits on how much of a chemical people should be exposed to over the course of their lives to avoid health risks.

The levels of PFOA and PFOS detected in Latkanich’s water were 280 times higher and 379 times higher, respectively, than the new federal thresholds.

Ng noted that PFAS contamination is widespread in U.S. drinking water, and though they’re well above the EPA’s new guidelines, the levels in Latkanich’s water aren’t uncommon.

“These health advisory limits are basically saying that these compounds are a health concern even at very low levels,” she said. “But at the same time, you’d be hard pressed to find water in the United States that doesn’t exceed those thresholds.”

A dangerous lack of transparency

A drilling rig in Washington County, PA.

Credit: Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance, 2016

In Pennsylvania, fracking companies must publicly disclose what chemicals they use, but they’re permitted to withhold “trade secrets.” This exemption is used frequently. “Secret” ingredients were used in more than half of Pennsylvania fracking wells developed between 2013 and 2017, with the most heavy usage of secret chemicals occurring in southwestern Pennsylvania, where Latkanich lives.

Pennsylvania isn’t alone. Most states with oil and gas development have trade-secret loopholes in their chemical disclosure laws. In Colorado, for example, 414 million pounds of chemicals used in the state’s fracking wells were left unidentified as “trade secrets” between 2011 and 2021, according to a 2022 report from Physicians for Social Responsibility.

In some states, like Pennsylvania, oil and gas companies are required to disclose complete lists of fracking chemicals to regulators, including ingredients that are withheld from the public as trade secrets. However, a new report, published this month by Physicians for Social Responsibility, found that manufacturers of the chemical mixtures used in fracking wells aren’t required to disclose complete lists of ingredients to oil and gas companies in most of those states, including Pennsylvania.

“Chemical manufacturers know best what ingredients are being used, but they often don’t tell companies further down the supply chain because they don’t have to,” said Horwitt, lead author of the new report. “This means regulators might not be getting the information they’re supposed to.”

“They knew this stuff could be in there, but they never looked for it”

Bryan Latkanich in his Washington County, PA home.

Credit: Connor Mulvaney/EHN

Latkanich’s drinking water has been plagued with problems since two fracking wells were drilled in his backyard in 2011 and 2012. The wells were plugged in 2020, but because PFAS are so persistent, Ng said, it’s possible that contamination built up in the plumbing and pipes.

Numerous organizations have tested the Latkanich’s water, including Environmental Health News, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) (DEP), and Chevron, the company that drilled, operated and plugged the fracking wells on Bryan’s property.

Environmental Health News’s testing found chemicals including butyl cyclohexane, tetradecane and naphthalene in Latkanich’s water. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection found methane and radium, but has stated Chevron is not responsible for any contamination because similar contaminants were detected in pre-drill water samples. Chevron also tested his water and maintained that their wells did not cause contamination.

But no one had tested Bryan’s water for PFAS before now.

“The DEP isn’t checking for this stuff because they don’t want to find it,” Latkanich said. “I’ve been trying to figure out what’s wrong with my water since 2013. They knew this stuff could be in there, but they never looked for it.”

Despite repeated requests, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection refused to answer questions about whether they’d received complete lists of the chemicals used in the wells on Latkanich’s property from Chevron, and why the agency had never tested his water for PFAS.

Agency spokesperson Neil Shader said the agency is conducting a new investigation into Latkanich’s water. He refused to say whether the investigation will include screening for PFAS. Latkanich said he had not heard from anyone at the state agency regarding a new investigation and that they had not collected any new water samples.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection recently tested drinking water throughout the state for PFAS, but those tests didn’t include any private wells or drinking water sources near oil and gas sites.

Shader refused to answer questions about why the agency didn’t look at oil and gas sites as part of its statewide PFAS investigation and whether it will do so in the future.

Pennsylvania is second in the nation for the number of private wells (behind Michigan). More than three million Pennsylvanians rely on private wells, mostly in rural areas where oil and gas development occurs. Private wells aren’t regulated in the state, so people living near oil and gas sites who are concerned about PFAS currently have no option but to pay for their own testing, which costs around $200 per sample, according to Ng.

“We should be thinking about how to enable more widespread testing of well water throughout Pennsylvania to figure out the potential scale of this problem,” Ng said.

Unsolvable mysteries

When he found out that PFAS were in his water, Latkanich initially thought it might prove that the fracking wells on his property had caused the contamination.

“Then I found out every place seems to have these things,” he said.

Chevron publicly disclosed using “nonionic fluorosurfactants” in 38 records in Texas and New Mexico from 2013-2015, according to public records accessed through OpenFF, a tool for searching public disclosures related to fracking chemicals. Nonionic fluorosurfactants may be PFAS, or may include chemicals that can break down into PFAS, according to Ng.

Chevron refused to answer EHN’s questions about its use of nonionic fluorosurfactants, about whether these compounds or PFAS were ever used in the wells on Latkanich’s property or any of its other Pennsylvania wells, and about whether it had ever disclosed complete lists of the chemicals used in Latkanich’s wells to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.

“Mr. Latkanich has raised concerns with Chevron and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection about various issues since 2011,” Chevron spokesperson Deena McMullen said in an emailed statement. “His repeated accusations that Chevron contaminated his water and damaged his home have been disproved.”

Without a complete record of the chemicals used in the fracking wells on his property, there’s no way to solve the mystery of whether Latkanich’s PFAS contamination came from the wells or some other source.

Plumber’s tape or plumber’s grease used in the home could contain enough PFAS to explain the levels of some of the chemicals, Ng said, while others are less easily explained by common household contamination sources.

For example, PFDS, which was detected in several of Latkanich’s samples, was phased out of most consumer products years ago.

Latkanich has been buying bottled water for years, but he and his son still bathe with well water. That’s a less direct exposure than eating or drinking PFAS, Ng said, but is still a source of exposure.

Scientists are still learning about the potential harms of exposure for most PFAS, but PFOS and PFOA have been studied extensively.

Exposure to both PFOS and PFOA have been linked to elevated cholesterol, changes in liver function, changes in thyroid hormone levels and reduced immune response. Exposure to PFOA has additionally been linked to an increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer.

Both of those compounds were found in Latkanich’s water at levels hundreds of times higher than the EPA’s health advisory levels, “but it’s hard to look at one sample of water and say, ‘this is what you can expect in terms of health effects,’” Ng said.