hurricane florence climate change

In North Carolina, hog waste pollution a familiar result. Will things ever change?

As Hurricane Florence floods dozens of hog waste pits, many in the state are wondering when the broken factory farm system will be fixed

NEW BERN, NORTH CAROLINA —The full extent of Hurricane Florence's environmental damage isn't yet known in North Carolina, where waste from factory farms, coal ash, and other pollutants are contaminating floodwaters still on the rise after the largest East Coast deluge north of Florida in history.

But there's at least one chapter in the unfolding Florence epic that's been written before: Open-air pits of animal feces – periodically reduced by spraying excess liquid onto crop fields – are spectacularly ill-suited to hurricanes and tropical storms.

In a changing climate, these events are becoming more frequent and severe, and clean water advocates say it's more urgent than ever to shut down waste pits in areas most likely to flood and to phase out the antiquated systems altogether.

After the storm passed, the network of riverkeepers took to the air again, patrolling for flooded waste pits and more illegal spraying. All week the group has documented problems that track with regulators' running online tally of waste pit failures, which is based on reports from farmers. As of noon Thursday, more than 100 pits were impacted by the storm, a handful with structural damage and dozens having overflowed or inches away from doing so.

The riverkeepers painstakingly track the violations and send them to state officials, who normally might investigate the problems firsthand and later penalize wrongdoers. Right now, though, the watchdogs say their aim is less to punish individual farmers and more to highlight the impossible position the industry's outdated waste control strategy puts them in.

"We're just doing our due diligence to continue to have that stockpile of evidence that this is a bad practice and needs to be changed," Matt Butler, program director at Sound Rivers, a member of the Waterkeeper Alliance, told EHN.

So far, he said, "with Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and now with Florence, we just keep repeating the same mistakes."

‘Making this soup of eastern North Carolina’

Duplin, NC. Photo taken Sept. 17, 2018. (Credit Waterkeeper Alliance, Inc.)

New factory-scale farms with waste pits have been banned here for more than 20 years. Yet with 9 million hogs, North Carolina still produces the second most pork in the country. Dominated by multinational corporations that contract with local farmers, the industry is concentrated in the state's low-lying southeastern coastal plain – exactly where Florence shattered rainfall records

Even in fair weather, the state's 2,100 facilities, all decades old, pose problems. . Odor and pathogens from animal barns, waste pits, and spray fields can torment and sicken neighbors, prompting three juries this year to award hundreds of millions in damages to plaintiffs suing Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork producer. Other suits are in the offing.

A Duke University study published online this week reinforced these neighbors' concerns, citing low life expectancy in communities near confined animal feeding operations, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors known to affect health and lifespan.

All of these threats are amplified after heavy rains. Fields saturated with rainwater can't absorb nutrients from waste pits; excess nitrogen and phosphorous instead appear in rivers and streams, at worst causing algae blooms and fish kills. Manure pits can burst or overflow, sending sludge, microbes, and potentially antibiotic-resistant bacteria into floodwaters, heightening their risk to public health.

"You're releasing all of that and making this soup of eastern North Carolina," said Ryke Longest, director of Duke University's environmental law clinic.

Hurricane Floyd in 1999 was a worst-case scenario, causing structural damage to six waste pits and flooding 55 others, according to the North Carolina Pork Council. Tens of thousands of hogs perished. After the flooding receded, water sampling revealed dangerous levels of E. Coli andother bacteria associated with food poisoning, the Waterkeeper Alliance and the Environmental Working Group say.

In the storm's wake, policymakers established a voluntary buyout program to move hog operations from the 100-year floodplain, the areas near rivers and creeks with a 1 percent annual chance of flooding. The initiative had initial success, shutting down more than 100 waste pits at 43 facilities at a cost of $18 million. Officials estimate 32 of them would have flooded during Hurricane Matthew in 2016, the last monumental storm to ravish eastern North Carolina.

Past time for new technological requirements

Photo taken Sept. 18, 2018, in Greenevers, NC. (Credit: Waterkeeper Alliance Inc)

Until this year, however, the program hadn't received a new injection of funds in more than a decade, and about 60 factory hog farms remain in the 100-year floodplain. It's too early to tell how many of these facilities are the ones now overflowing, but state officials, the pork industry, and environmental advocates agree investing more in the program should be a priority.

"We've had very diverse support from a variety of groups," said Vernon Cox of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, who oversees the program, "and we believe there's a benefit for everybody involved. We're able to help [farmers] out of a difficult situation — as well as the environment."

Still, most experts say focusing only on the 100-year floodplain would be a mistake. Thanks to climate change, heavy rains are expected to be the new normal. Florence was considered a 1000-year storm; Matthew from two years ago was considered a 500-year storm.

At the same time, many farmers whose lagoons are now on the verge of overflowing face a difficult choice of violating their permits by spraying onto fields, harming rivers and creeks in the long term, or risking direct discharge of waste.

Regulators haven't yet decided whether to relax spraying limits, but they have in the past.

"The reality [is] that spraying on saturated soils may be the lesser evil as compared to risking additional breaches after the storm," said attorney Robin Smith, a former state assistant secretary with North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

Related: Peak Pig — The fight for the soul of rural America

That's why advocates say all hog facilities should phase out open-air waste pits and convert to more sustainable systems already used in other states and countries. They point out the DEQ has the opportunity to push for just that this fall, when it debates renewed permitting standards for existing farms.

"They [keep] renewing the permit on these old, old lagoons as if these things are brand new, yet many of them have been in service for more than 20 years," Longest said. "They are over time going to be prone to leak, and the hardware and equipment associated with them over time is going to break down and need to be replaced."

"As that time comes around," he continued, "the Department should determine which of these are failing – and have failed – and then new technological requirements should be placed on those farms."

By covering waste pits, capturing methane gas from the waste, and burning it to create electricity, hog facilities can both limit water pollution and curb potent greenhouse gases. Eleven farms around the state capture and convert biogas today.

Tom Butler, one of the farmers with a lagoon cover, said earlier this year it stopped 2.8 millions of rainwater from becoming waste during Hurricane Matthew.

"I love to tell this story," Butler said with pride. "When a raindrop falls into an open lagoon, it becomes part of your farm's waste, when it falls on our cover we just pump it off."

Easier said than done

(Credit: Waterkeeper Alliance Inc.)

Of course, all of these solutions are easier said than done. The state's DEQ is understaffed and underfunded, its budget slashed by more than 40 percent since 2012. Even before the GOP took control of the Legislature in 2010, regulators faced pressure from a political establishment anxious to protect the state's largest industry, a multi-billion endeavor.

At the same time, decades of bitter battle have calcified distrust between the pork industry and environmental advocates, making even meager progress toward better waste technology like biogas contentious.

Nuisance lawsuits and the spotlight on the industry due to hurricanes has put the North Carolina Pork Council, Smithfield Foods, and their allies on the defensive. They point out that breaches and floods tend to occur on just a tiny fraction of the state's 3,700-some waste pits.

"While some of our farms did experience damage, the impact was relatively minor considering the extreme severity of the storm and our expansive footprint in the state," Kiera Lombardo, senior vice president of corporate affairs for Smithfield, said in a statement after Florence.

State agricultural officials estimate 5,500 hogs and 3.4 million poultry are dead, most trapped in barns flooded by the storm.

And while Waterkeepers' dogged air patrols have caught contract farmers violating the law, they say the real culprits are the giant corporate conglomerates that take no responsibility for the waste their hogs produce.

"It probably sounds a little strange coming from an environmentalist, but I do feel for these people who have invested their entire lives into growing hogs under a system that is broken," said Crystal Coast Waterkeeper Larry Baldwin. It should be up to Smithfield and its cohort, he said, "to say how do we take some of the billions of dollars that we're making in profit and turn it back around to find a better system."

Smithfield and the Pork Council did celebrate in April when $5 million was added to the floodplain buyout program, though it is expected to close down lagoons on only four to six facilities. Cox, with the Department of Agriculture, said an agreement with the federal government for some of these funds was finalized just last week, and the state will start taking applications by the first of next year.

In the meantime, advocates like Baldwin will keep pushing for even more meaningful reforms and hoping the next big storm doesn't come too soon.

"We're not even through hurricane season yet," Baldwin said.

Peter Dykstra: The many faces of Florence

The list of risks from major storms expands.

As Hurricane Florence continues its wet, windy rampage, here's my attempt to gather some of the stray baggage that hurricanes leave us.

Bolstered projections—and populations

Myrtle Beach, SC. (Credit: Gerry Dincher/flickr)

In October 1954, Hurricane Hazel tore through the Caribbean and the Bahamas, killing as many as 1,000, mostly in Haiti. Hazel hit the Carolina coast, flattening beachfront structures from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, north to the Outer Banks. The storm turned inland, with flooding rains contributing to 95 more deaths in the U.S. Remnants of the storm killed 81 more in the Toronto area, making Hazel a billion-dollar storm in Canada alone (in 2018 dollars.)

Two important differences separate a 1954 killer storm from a killer storm today: First, weather prediction and risk communication were still relatively primitive back then. Today the lifesaving role of both government and TV meteorologists has been key in keeping death tolls low.

But with climate change increasing the frequency and intensity of storms, even those lower death tolls are a hollow victory.

Also, sleepy coastal towns like Myrtle Beach are sleepy no more. The city has grown tenfold since 1950, when there were 3,000 year-round residents. Many hurricane-vulnerable beach towns along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts can tell the same story – real estate booms creating far more potentially destroyable property.

All those extra people packed into hurricane targets like Myrtle Beach, or the state of Florida (2.8 million in 1950, 21 million today) turn evacuations into logistical nightmares and political timebombs.

In 2005, with America still stunned by the horrific drama of Hurricane Katrina, Houston staged one of the largest and most ill-fated evacuations in history. An estimated 2.5 million people clogged the roads out of town from metro Houston to escape a likely direct hit from Hurricane Rita.

There were road rage fistfights, heat stroke, and families marooned in gridlock for 24 hours. Fire consumed a bus full of senior citizens stuck on the interstate, killing 24.

Rita only grazed Houston, and the storm's direct death toll was less than half that of the flaming bus. The press and public tore into public safety officials and city leaders for the tragically counterproductive decision.

Twelve years later, Houston area leaders opted not to evacuate from Hurricane Harvey, and took grief for their decision once again.

Florence fear

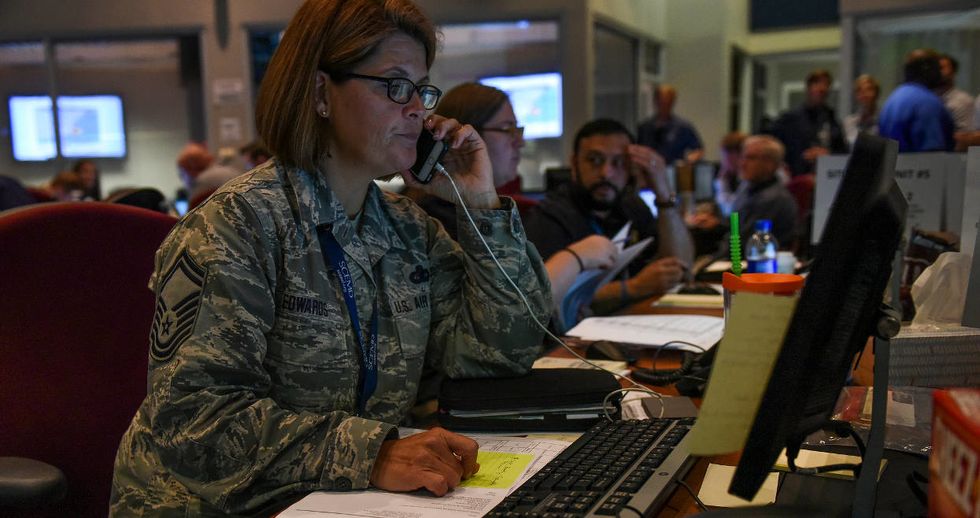

SC National Guard

The earliest, most dire reports of Florence's potential damage prompted Maryland's governor to join his counterparts farther south in proclaiming a state of emergency. The prophylactic emergency declarations are equal parts butt-covering and pragmatic politics. They offer some insulation against charges that leaders were unprepared, but more reasonably, they grease the skids for federal disaster aid if it's needed.

But even if Maryland dodges major damage, severe storms have a special impact in Chesapeake Bay, where doomed islands and their centuries-old cultures are yielding to a combination of land subsidence, erosion, and sea level rise. Hurricanes like Isabel in 2003 brought storm surge roaring up the Bay, accelerating the eventual disappearance of Smith Island and Virginia's Tangier Island.

Hurricanes cause erosion along coastlines from Cape Cod to Texas.

On Thursday, Duke Energy executive David Fountain told CNN that the major utility in the Carolinas expected to see 75 percent of its customer base lose power from Florence. 2017's Hurricane Irma knocked out electricity for two-thirds of Florida's 10 million households.

Duke and other utilities own and maintain (or not) roughly six dozen coal ash impoundments in the vast area that is forecast to see days of deluge from Florence. Nuclear plants, like Duke's Brunswick station near Wilmington, have shut down. EPA says it's monitoring nine Superfund sites in the storm's path. Forecasts of rainfall measured not in inches but in feet could also overwhelm sewage treatment plants.

Hogs are one of North Carolina's leading cash cows and the forecast for extended rainfall is causing panic among farmers and their neighbors. In the 1990's, two events helped bring attention to the growing risks of hog waste pollution in North Carolina. First, the Raleigh News & Observer won a Pulitzer Prize for its series "Boss Hog" on porcine power and pollution in the state. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd's relentless rainfall prompted spills from dozens of hog waste lagoons. Since then, the industry, and even the hogs themselves, have grown considerably.

EHN's 2017 series "Peak Pig" focused on the industry's continued problems.

And Florence may bring the pigs home to roost.