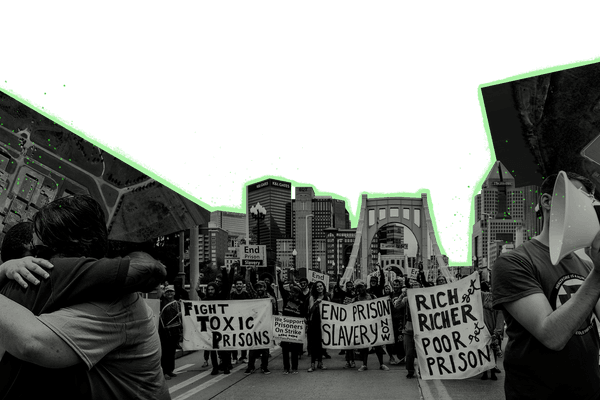

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was a record-breaker, and it’s raising more concerns about climate change

Here's what research tells us about the 2020 season and what may be ahead.

It was clear before the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season started that it was going to be busy.

Six months later, we're looking back at a trail of broken records, and the storms may still not be over even though the season officially ended on Nov. 30.

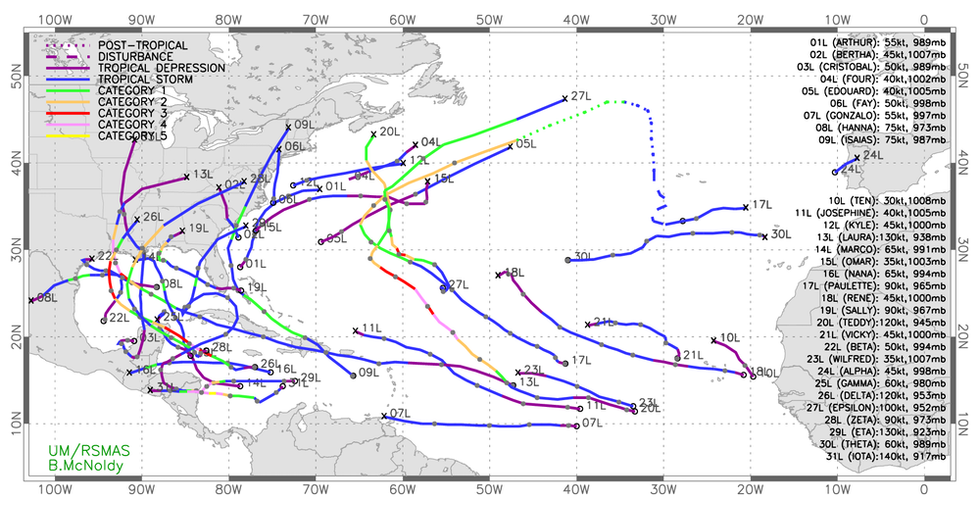

This season had the most named storms, with 30, taking the record from the calamitous 2005 season that brought Hurricane Katrina to New Orleans. It was only the second time the list of storm names was exhausted since naming began in the 1950s.

Ten storms underwent rapid intensification, a number not seen since 1995. Twelve made landfall in the U.S., also setting a new record. Six of those landfalling storms were hurricane strength, tying yet another record.

Tropical storm tracks show how busy the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was. (Credit: Brian McNoldy, CC BY-ND)

As atmospheric scientists, we target our research at better understanding both what drives the formation of tropical cyclones and how climate change is affecting them on longer time scales.

Here's what research tells us about the 2020 season and what may be ahead.

Why did 2020 have so many storms?

An unfortunate combination of two key factors made this season ripe for tropical storms.

First, a La Niña pattern of cool surface waters developed in the equatorial Pacific, and it was stronger than anticipated.

Ironically, cooling in the equatorial Pacific makes it easier for tropical storms to form and gain strength in the Atlantic. That's because La Niña weakens the vertical wind shear over the tropical Atlantic. Vertical wind shear – a change in wind speeds with altitude – is highly disruptive to storm development.

As the La Niña pattern became established this season, it made the tropical Atlantic much more hospitable for storms to form and intensify.

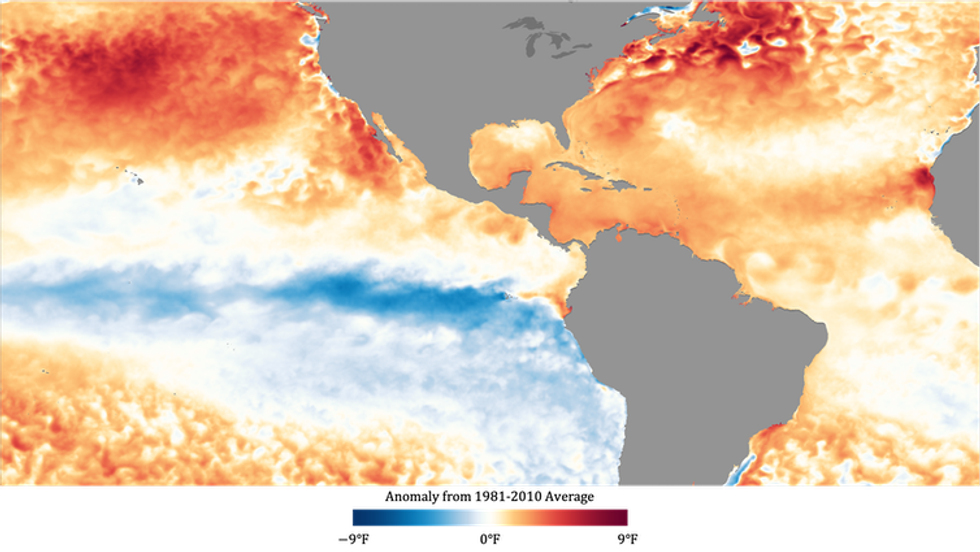

Atlantic sea surface temperatures in September 2020 were warmer than the 1981-2010 average. (Credit: NOAA)

The second critical factor was the extremely warm temperatures in the Atlantic, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

Hurricanes are powered by the transfer of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere. The sea surface temperature therefore dictates the maximum potential intensity a storm can attain under perfect conditions – it's like a thermodynamic "speed limit" on hurricane intensity.

The sea surface temperature approached record levels in the Atlantic hurricane basin this season, including in September, the most active Atlantic storm month on record.

What does climate change have to do with it?

An important part of this season's story is the Atlantic warming trend we're witnessing, which is unprecedented going back at least several millennia.

The oceans store much of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases. With greenhouse gas concentrations still increasing due to human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels, average sea surface temperatures are likely to continue rising over the coming decades. Whether climate change caused the extremely high number of storms this season is unclear. There is no detectable trend in global hurricane frequency, and computer modeling studies have had conflicting results.

However, the warming climate is increasing the threat posed by hurricanes in other ways.

A growing proportion of high-intensity storms, Category 3, 4 and 5, is being observed around the world, including in the Atlantic. Since ocean temperature controls the potential intensity of tropical cyclones, climate change is likely behind this trend, which is expected to continue.

The U.S. is also seeing more storms with extreme rainfall. Think about Hurricane Harvey's 50 inches of rain in the Houston area in 2017 and Florence's 30-plus inches in North Carolina in 2018. The warming climate plays a key role here, too. With warmer temperatures, more water is able to evaporate into the atmosphere, resulting in greater moisture in the air.

Implications of the 2020 season

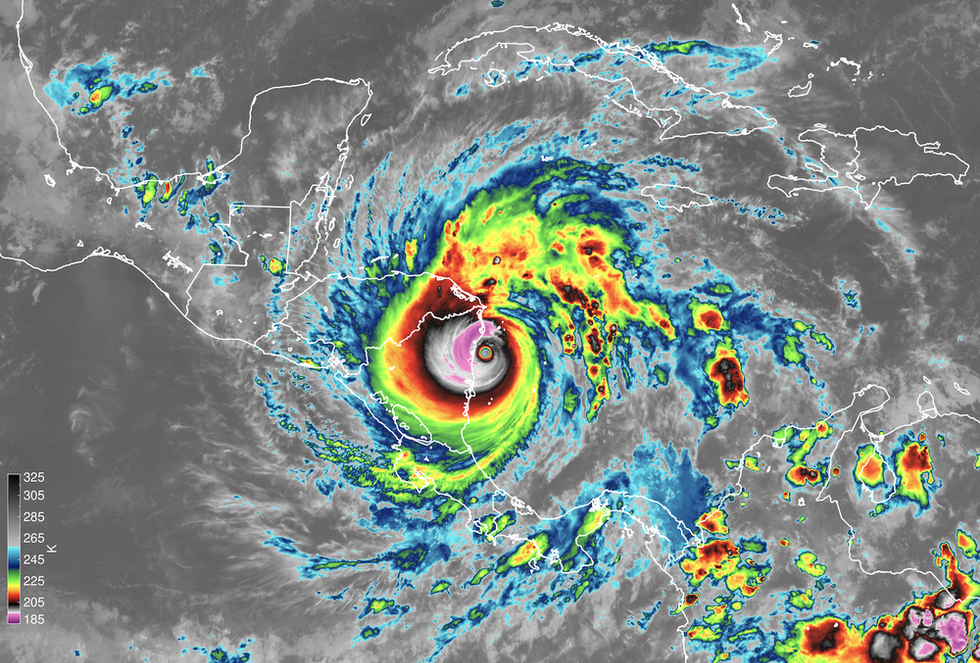

Ten storms this season underwent rapid intensification – a 35 mph increase in maximum winds within 24 hours. Rapidly intensifying storms are especially dangerous because 1) they are challenging to accurately predict, and 2) they provide minimal time for evacuations when they intensify just before making landfall.

Satellite instruments capture Hurricane Iota making landfall in Nicaragua on Nov. 16. The image shows the temperature of cloud tops, which tells scientists how tall the clouds are. (Credit: NOAA; James H. Ruppert Jr.)

Hurricanes Laura and Sally both rapidly intensified just before making landfall on the Gulf Coast this season. Eta rapidly intensified to a Category 4 just before hitting Nicaragua, and just two weeks later, Iota essentially repeated the act in the same location.

Forecasts for the tracks or paths of tropical cyclones have dramatically improved in recent decades, as much as five days in advance. However, forecasts of storm formation and intensification have improved very little by comparison.

The forecasts for hurricane rapid intensification are especially poor.

While the official forecasts issued by the National Hurricane Center are issued by human forecasters, they depend on the guidance of prediction models, which aren't very accurate when it comes to rapid intensification.

The complexity of weather models makes this a daunting challenge. However, it becomes more tractable as researchers learn more about how hurricanes form and intensify and identify the root causes for errors in computer model predictions.

Our latest research explores how clouds create their own greenhouse effect, trapping heat that causes hurricanes to form and intensify more quickly. Improving how numerical models account for this cloud feedback may ultimately hold promise for more accurate forecasts. Innovative ways of collecting new measurements in developing storms, down to their smallest scales, will also be necessary for guiding these improvements.

Given the upward trend in high-intensity storms, the risks from these storms will only grow. The ability to accurately predict how and when they will form, intensify and threaten coastal populations is crucial.

James H. Ruppert Jr. is an assistant research professor at Penn State. Allison Wing is an assistant professor of meteorology at Florida State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.