endocrine disruptors

LISTEN: Timnit Kefela on treating plastic pollution as an environmental justice issue

“I’m optimistic we can get this right.”

Dr. Timnit Kefela joins the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice podcast to discuss the the specific ways microplastics harm urban communities and some of her tips for reducing plastic use and exposure.

Kefela, who is starting as an assistant professor in environmental science and resource management with a focus on environmental justice at CSU Channel Islands this fall, also talks about what she sees as a path forward in tackling the plastic waste crisis.

The Agents of Change in Environmental Justice podcast is a biweekly podcast featuring the stories and big ideas from past and present fellows, as well as others in the field. You can see all of the past episodes here.

Listen below to our discussion with Kefela and subscribe to the podcast at iTunes or Spotify.

Transcript

Brian Bienkowski

I am really excited to be joined by Timnit Kefela. Timnit, how are you doing today?

Timnit Kefela

I'm doing all right. How are you?

Brian Bienkowski

I'm doing wonderful. And where are you today?

Timnit Kefela

I'm calling in from Tempe, Arizona. So 117 degree weather, yeah.

Brian Bienkowski

So I am from the Upper Midwest, and everybody says, but it's a dry heat down there in Arizona, whereas here we get this, we get this very oppressive humidity and mosquitoes and all that. So does the dry heat make a difference?

Timnit Kefela

It does, you feel less suffocated, but it's still really hot. You definitely cannot go for walks during the day. You got to stay inside. But I will say it feels a little bit, a little bit more manageable considering the temperature. But you don't want to be out there long enough to be sunburnt or, you know, have heat stroke, something to that effect.

Brian Bienkowski

So that reminds me of something, and I want to get to some of the questions that I had prepared, but I have to ask you something that I didn't ask you in person. So we have a retreat that we went to. And I am a runner, so I wake up early and I run. And one of my early runs, the only other human I saw outside was you walking around, and I didn't know if you were a fellow morning person, if you like birds, if you needed to clear your head, or if that's just something that you do?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, I'm not a morning person. Actually, I'm a morning person out of necessity. But I went to school close to where the retreat was happening in Pennsylvania. I went to school in New Jersey, and I really, really loved the nature there, so I was taking the opportunity to just go walk and be amongst the trees and take it easy, take deep breaths and experience the Northeast forest life, which I hadn't experienced in many years. So that's kind of why you saw me out there. Otherwise, no, I am not a morning person. It requires a lot of caffeine in order for me to function in the morning.

Brian Bienkowski

I love that. I'm sorry for putting your business out there that you were walking at our retreat, but I was going to say something you, but you did look very peaceful, I have to say. So I was like, You know what? I'm just going to leave her alone. Leave her, leave her with the trees. Well, Timnit tell me about, of course, you're not from, originally from Arizona, so tell me about your upbringing and your family's journey to the US.

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, I'm from a small country in northeastern Africa, next to the Red Sea, right above Ethiopia, known as Eritrea. But I was born and raised in Nairobi, Kenya, as a lot of Eritreans were because of the Eritrea-Ethiopia war, and Kenya was one of the few stable nations in the region where there was a lot of conflict. So Kenya was this like haven for many of us. So it's a place that gave me and my family safety at that point in time. So I like to say that I'm both from Kenya and Eritrea, because they're a big part of my identity. I then moved to the United States because my family actually ended up winning the green card lottery and ended up settling in the DC, Maryland, northern Virginia area.

Brian Bienkowski

So where along the way did you become aware of the concept of environmental justice, and what did that look like?

Timnit Kefela

I think I inherintly knew what environmental justice was because it was a lived experience of mine where pollution, poor infrastructure and the resulting illnesses from these factors were just what life entailed. That was what normal was for me. However, when I went to college –shout out Camden!– I had the opportunity to learn what this experience was called, and this further emphasized with working on community-based initiatives. I worked in an after school program focused on urban gardening. I got to witness you know, what it meant to be living in environmental injustice, or experiencing environmental injustice, especially when I witnessed my students touch soil for the first time, and how much joy they felt, and how they did not get to experience it sooner because they grew up understanding not to trust their environment, which is an experience I also had. So I would say that my understanding and awareness of environmental justice is a personal one, both from my lived experience as well as bearing witness to what my students were experiencing during my time in Camden, New Jersey.

Brian Bienkowski

So I have a very similar story before I got into environmental journalism, I worked in urban gardening in Lansing, Michigan, and they had converted a lot in an underserved neighborhood into a couple acres of a garden. And the same experience I, you know, I saw where there were children, first of all, it became like this kind of community epicenter, because it was the most beautiful part of the block, right? You had things growing and green space and places to hang out. And many of the kids, of course, weren't, weren't aware of gardening and getting their hands in the dirt, because they lived in a very kind of dense urban block there. So I have a very similar experience, and I still miss urban agriculture. I live very rural now, so I have big agriculture, but I do, I definitely do miss that, because I think there's something really special about watching kids who don't have access to green space fall in love with some of that stuff. So Timnit, what is a moment or event that has helped shape your identity?

Timnit Kefela

So many moments, so many events have shaped my identity, which I feel like is ever-evolving. Um, as you know, life goes on. Honestly, I never thought if we were to talk about like, my identity as an environmental scientist. I never thought be an environmental scientist. I don't think I ever understood what that was as a kid. In fact, if you ask my parents, I floated the idea of being a musician or a poet because I used to like to sing and I used to love to write as career options, especially in my teenage years. You know the feeling years, and my parents looked at me and they were like, maybe just consider being a medical doctor, which is like something that the General Pipe Dreams. Immigrant pipe dreams are, you know, getting from your parents. And so when I went to college, that was what my focus was on, primarily, you know, pre med, but mostly focusing on biology. But then I began taking a lot of gen ed classes focused on the humanities, where I learned a lot about what environmental justice was, and even as I was going through my science courses, I started learning that I could leverage science to ask questions and address issues that impacted my community and that of my students. So essentially using it as a vehicle of agency. I also learned that I really love mentoring and teaching during that time as well, which then led me down this path, which has been long, winding and at times pioneering, and is emboldened by the amazing community I have been blessed with.

Brian Bienkowski

So your research focuses on micro plastics. This is near and dear to my heart, We cover this a lot at EHN, and I think this issue is becoming more familiar to people. But can you just give us a rundown of how you define microplastic and why it seems to be contaminating everything, including us?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah. Microplastics are small pieces of plastic, as implied in the name, that are less than five millimeters in size. So we're talking smaller than the width of a number two pencil eraser. They can be deliberately made that size, which we typically categorize as primary microplastics, and some examples of those are glitter, which add a little dazzle in our lives; microbeads, which are used as abrasives and laundering products; or pre production plastic pellets, which we affectionately call nurdles. But more significant type of microplastics are those that we actually categorize as secondary and this means that they're formed by breaking apart from larger plastic items, either by using them. So think about when you're driving a car. Or riding your bike, small pieces of plastic are falling off of your tires, right? And that's why you eventually need to replace your tires, because the tread goes or it could be that you have a plastic item, like a water bottle that is left out in the environment. It's exposed to sunlight, and it undergoes a chemical process known as oxidation, which makes it really brittle, and all it really takes is some kind of force to cause it to break apart into smaller pieces, which we know as microplastics. And that force could be waves in a water body, or it could even just be trampling on this really brittle piece of plastic. Microplastics have been found everywhere, and that's no exaggeration. I know you cover it quite extensively in EHN, because of how much plastic there is in the world. We've produced more than 8 billion metric tons of plastic, of which 6 billion metric tons have become waste that do not degrade, and they, in turn, end up accumulating in our environment or in landfills. So we have such a large volume of this material in our world, and that's why we see them everywhere, because unfortunately, it is a plastic-filled world, after all.

Brian Bienkowski

and when Timnit says, everywhere – iMicroplastics have been found in the Mariana Trench, in the deepest parts of the ocean and atop Mount Everest. So it really is kind of from the bottom to the top. It's really scary stuff. So what are the human health concerns? I think we think of, you know, maybe a duck ingesting plastics, and there's the physical obstruction. But I know that the concerns go beyond that. So what are the human health concerns with all this plastic around?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, so human health concerns regarding plastic are present. I think it's really important to note that they're present throughout the life cycle of a plastic. So be it chemical exposure, whereby additives, which are chemicals that give plastics their desired properties, like they make them more flexible, or if we want our plastic to be a particular color or more resistant to sun exposure, these chemicals can leach into our food and our environment. Some of these additives, like phthalates, are known to disrupt the function of our endocrine systems, whereby the chemicals end up mimicking or blocking or interfering where our body's hormones tend to to need to go to work, right? and are incredibly crucial to regulate our bodily functions and processes. And disruption of this system can lead to numerous human health issues, ranging from metabolic disorders to fertility issues. And some of these additives, too, are known carcinogens, specifically phalates, for example, meaning that they can increase the risk of developing cancer with prolonged exposure. So looking at that and the production and use phase as well as these chemicals can potentially migrate or leach out of these plastics, and could potentially trigger such effects in our health. Additionally, I think it's important to note that the production of plastics from petroleum refining to, you know, ethane cracking in the natural gas industry, which is where, like a lot of the raw materials for plastics come from to the consumer-ready stage, contributes to a significant amount of air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, as well as other types of volatiles that are released into the atmosphere. And as a result, communities that are co-located with these facilities and those who work in these plants are likely to develop respiratory-related illnesses and cancers. I think about Ohio River Valley, as well as Cancer Alley in Louisiana, when thinking about looking at the impacts of the production of plastics. I think it's important to note, however, when they do become microplastics, that they're both essentially physical and chemical pollutants. So the additives, which are those chemicals that you add to plastics, can account for up to 15% of the total polymers weight, and they can leach out and yield harm in our bodies. It's also important to note that it could be, you know, when they're putting these chemicals in to create these desirable properties for these plastics, they might seem pretty stable, however, when they're out there in the outdoor environment, they could potentially transform and then cause harm as well. Another source of human health impacts is also thinking about the inhalation of microplastics, which are essentially particulate matter. I know we talk a lot about particulate matter when we're thinking about air quality, microplastics are part of that, and they have been linked to respiratory-related illnesses in occupational health settings. Presence of microplastics in arteries show higher incidences of heart attack and strokes. A lot of the work on human health impacts, however, is definitely not fleshed out. I think that a multitude of studies are being developed, especially since now that we have confirmed that they are, in fact, in our bodies. And it's really cool that we get to see medical organizations like the American Lung Association making statements about how it's really important to pay attention to this as being a cause of some serious human health concern. I think that also something that should be taken into consideration as we're ramping up this understanding on human health and microplastics, is understanding that they most likely are going to disproportionately impact people that are co-located with these facilities, as well as like the presence of where these landfills are, as well as the as being in urban areas who are already facing quite a lot of health issues as a result of poor environmental conditions and their air quality, soil quality, quality and water quality. And so it's really important to also take into consideration what the compounded impacts are as we begin to understand more and more about microplastics and human health.

Brian Bienkowski

Yeah, let's unpack that a bit, because I think similar to climate change in the initially it was polar bears. Right? With plastics, a lot of it has been focused on oceans and marine life. And obviously this is really important to understand and tackle these issues as well. But your interest in research lies in the cities and the people that live there. So what are, what are some of the microplastic concerns specific to urban environments?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, so they're equally important matrices to study. I just wanted to put that out there. I think much of the focus was on oceans and marine life, in part, because historically, that's where we saw plastics impact animals first. So I think the first recorded information –and recorded meaning, formally recorded in a journal– was in the 1960s where a rubber band was found inside of a puffin, right? So I think that we we relate to that specifically being why we hyper focused on looking on marine looking at marine life and oceans, as well as seeing this accumulation of plastics as a result of the dilution is the solution to pollution era whereby people would just throw stuff in the ocean because they're like, the ocean is vast. However, when you have materials that don't degrade, they just eventually just end up accumulating, right? But I do think that plastics being such a big part of our built environments also contributes to this expectation that there will be pollution or waste there, which is true, but it is important to note that more than half of the global population is expected to live in cities by 2050 and that just because we expect built environments to be polluted does not mean that we cannot strive for healthy urban environments. So in urban settings, microplastics can become airborne, largely because of vehicle emissions. It could be industrial activities that are present within those environments, as well as the wear-and-tear of plastic materials. In addition to that, these microplastics can then end up depositing on impervious surfaces, because if you think about it, in cities, we have a lot of pavement, we have a lot of roads, so the plastics just deposit on those surfaces, which can then be carried away through stormwater runoff into receiving water systems, and as a result, can end up polluting water resources that different people who live within those areas are dependent on for their livelihood. They could also enter our soil systems that support the green spaces, that help with temperature control in our cities, and these green spaces counter what is known as the urban heat island effect –whereby buildings, roads, and just generally, other structures typically absorb and re-emit the sun's heat more than green spaces do, so that's why we love trees, and that's why we like having shrubs in cities, because they can help modulate that temperature. So the presence of these microplastics and large concentrations of microplastics entering these soils and their impacts remain unknown. And I think it's really important to pay attention to how the to understand how microplastics may potentially be disrupting, like crucial relationships, mutualistic relationships. Is their presence disrupting the ability for the microbes to support these plant systems? or other fauna to support these plant systems, that results in these green spaces, you know, therefore not being that viable for a very long time and not truly resilient, as we have more loadings of microplastics entering there? Additionally, and I think that is incredibly necessary for us to study, especially as we are thinking about what it takes to build a resilient and healthy urban environment. Rivers and Lakes and canals in urban areas typically have, like, really high loads of microplastics due to that stormwater runoff that I've mentioned, as well as wastewater effluent or any kind of sewer discharges where there isn't necessarily, like any type of filtration mechanism, say filtration mechanism. So you know, when you see those signs that say, all drains go to the ocean, right? So, like that could be another way that they end up there. Additionally, I think it's important to also pay attention to how lower income areas within cities often will face higher levels of microplastic pollution, largely due to less effective waste management systems, greater reliance on plastic products as a result of not trusting their physical infrastructure to develop public goods –like water– that is healthy for them to trust, as well as having closer proximity to industrial activities. So like co-located with the production plants as well as the chemical plants, as well as where the waste management sites are. So I foresee this being something that we need to really pay attention to, because it will likely exasperate health disparities among different socioeconomic groups within a city, and further than make this it is very much an environmental justice issue, but it will widen the gap and really highlight how it is going to be a bigger environmental justice issue. If that makes sense.

Brian Bienkowski

It does make sense, and thanks so much for breaking it down, especially this idea of a life cycle. I think one region of the country that a lot of people would understand this is when we look at Cancer Alley, the Gulf Coast. So not only are these dense areas where a lot of the problems that you're speaking to that there are just more microplastics in these denser areas from tires and people's use that are getting into water and air, but also they are on the front end of the plastic when they're pulling the oil out of the ground, and they're refining the oil at petrochemical industries, and they're inhaling that. So it really is a kind of from start to finish, making these products is really impacting people's health. So let's get into some specifics. I know there's different kinds of microplastics and probably different kinds of people affected. So microfibers, for example, I'm a runner and a cyclist, so I'm guessing some of my clothes are throwing these into the environment, some of those weird spandex things I wear. But for example, these are small, plastic-based particles that shed from our clothes, these microfibers. So what kind of people might experience harm from these particles, specifically?

Timnit Kefela

Definitely, I think all of us, frankly, all of us, can be impacted by this, especially within our indoor environments. It's not only our clothing that are sources of microfibers, but also durable goods. So thinking about our carpets, thinking about our sofa sets and all of that like that in itself, too, are big contributors for microfibers. But I think a particularly vulnerable population are garment workers. So a big fear, or really just work as textile workers in general. A big fear about microplastics and human health is that we ingest them through our food, but inhalation is likely a larger pathway of entry into our bodies, and so inhalation of these microfibers by textile workers have been long documented, since the late 80s through occupational health research, and they're essentially particulate matter, and studies have shown that plastic particles that have been found in lungs are closely correlated with cancers, chronic lung diseases and reduced lung capacity and inflammation. And what's really cool about noting this is like, we kind of have an idea of like, the impacts that microfibers have on human health, especially in places with really high concentrations, and there have been interventions that have been studied from an occupational stance. So for example, using protective equipment like masks, or having engineering controls of sorts, where a lot of this construction of textiles are happening, like proper ventilation, those could potentially mitigate this harm. But workers often have to purchase the protective equipment themselves rather than have them provided to them, which can then be really difficult or cost prohibitive for them to actually have the ability to protect themselves from the impacts of this. I think something to also take into consideration is that a lot of textile factories are not necessarily the coolest places. They can be incredibly hot, so wearing a mask and other protective equipment can also be incredibly stifling. Some folks feel like the protective equipment slows them down, which impacts the required quota that dictates how they're paid, which invites us to really consider why the bottom line is always defined by money over health as well. And then in terms of like engineering control so like having proper ventilation within these garment rooms and textile factories that is primarily provided by the employers, of which not all employers will most likely invest in. So it's really important to note that they are very much a vulnerable population when we think about the impacts of microfibers on human health.

Brian Bienkowski

And I want to hammer a point home that I think you that you already made is when you're talking about this, as in carpets and furniture and clothing. So it's pretty ubiquitous, but at the same time, if people have means to replace the old couch with one that isn't shedding as much, or one that's used with natural materials, or they can get rid of their plastic water bottle because they can afford to get a fancy glass one, or whatever, this does become kind of an income class environmental justice issue where people are just unable to keep up with new products that maybe are not as contaminating in their homes.

Timnit Kefela

Absolutely.

Brian Bienkowski

So can you talk a little bit about your project in East Palo Alto, California that focused on community-based microplastic monitoring?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, absolutely. I have this really awesome opportunity to support and collaborate and co-lead a project in East Palo Alto, California with a phenomenal community-based organization called Nuestra Casa, colleagues of mine at California State University Channel Islands and the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, where community members are concerned about microplastics in one of the few green spaces that they have access to in the bay lands. So the purpose of this project is really just us helping train and support community members on the sampling and data collection of soil and water samples to monitor for these microplastics, which they can use in support of their own advocacy and education efforts, which I think is really great, and also really hones in on recognizing that community members are experts in their own right, and therefore should be the ones also having autonomy over projects like this, if they so, seek to do so. What's really cool about this project as well is that we get to investigate how the installation of a horizontal levee may limit microplastic movement from wastewater effluent that's being discharged in the bay as well. So it's like a double whammy. We get to come up with this really cool community-based microplastics monitoring program and support people in their education and advocacy efforts, but we also get to see if this nature-based solution that's being installed in the bay lands could also be potentially helpful for limiting the concentrations entering the bay.

Brian Bienkowski

Obviously this is a big theme on our podcast. Is kind of community engagement, community empowerment. But I have to say, every time I hear an example, it makes me excited. I love this idea of saying, here is the data. You are already the expert. Now you have a little bit more in your toolbox. So when they go to the community meeting or they are advocating for their communities, they know way more than these people that are making, the decision makers, and maybe it doesn't always work out, but hopefully that teeter totter is starting to balance the other way, where some of these communities are being heard, because now they are armed with even more expertise from folks like yourself. I really like that. So when it comes to plastic, I think every day we see a new think piece and op-ed promoting solutions, alternative, reduced use. We've we've reported a lot on chemical recycling and how problematic that that can be. So can you talk about why these are often inaccessible for the people most impacted a lot of these solutions, and have you seen any initiatives or solutions that are equitable and include tackling plastic pollution in a just way?

Timnit Kefela

Absolutely, I think... so, when reflecting on this, I think we often sit and consider how we can make a difference. When we're thinking about how we can make a difference about an issue, we often operate from our own living lens. So for example, if you have the opportunity to use a reusable water bottle because you trust the water that comes out of your tap, then that's inherently a privilege, right? Not everyone can do that. I certainly could not do that growing up, and so folks have to be reliant on bottled water to have access to clean drinking water. I think it is incredibly important to note that as we advocate for bans, we also advocate for better infrastructure that can ensure everyone can divest from using single use plastic. Presently, a lot of the reusable alternatives are suitable for folks who can afford them and trust the delivery of public goods like water, right? I also think about the disabled community when it comes to calls for these blanket bans when having access to, say, pre made foods, or having to engage in online shopping and deliveries or needing plastic straw. Allows for them to drink liquids or some kind of liquid nutrition, and how those are really crucial for their daily lives, and how a lot of the solutions that are being proposed are purchasable solutions, right? And something to take into consideration with that is that the cost of living of our disabled communities are typically often higher than non-disabled communities, and so they may not necessarily have access to reuse alternatives, alternatives all that much. So I think it's really important to consider that we can ask for production caps for non essential plastics, but also center the needs of disabled people to have a fraction of plastic available without stigma, until substitutions are designed with their needs in mind. A lot of these reusable substitutions are not designed with their needs in mind, right? So I think there also needs to be a push for the development of material substitutions that have them prioritized. I have seen solutions proposed that work for certain facets of people, but not necessarily everyone. It requires a lot of consideration of infrastructural equity, regulation and accountability, of plastic production and waste management, and most importantly, using the voices of those most impacted as a guiding design for principles for solutions. So I can't necessarily say that I have borne witness to just initiatives, really per se, or equitable initiatives. However, I do think that with continuous conversations that I've seen across different sectors and different stakeholders that we are getting closer to that. But I think it's really important that we center the right voices in these conversations in order to truly do that, yeah.

Brian Bienkowski

And I think what happens a lot of times in plastic conversations is some of those voices carry so much more weight because they are the same people. They are the same voices in the climate conversation that are pushing for increased drilling and and natural gas extraction and stuff. So you know, your point about thinking, thinking about the disabled community was your example, but just in general, I think that's such a good lesson in all of these issues is just to it's such a basic kindergarten lesson. But put yourself in someone else's shoes and think about how this is impacting other folks before we just jump into our camps and we need a ban. We need, you know, I think, just think that is such a such a valuable lesson, and I really appreciate that. So there is a global plastic treaty that's been in the works for years now, which would be the first international effort to tackle plastic pollution, and there's been some disagreement over things like chemical recycling and bans, and it's kind of the usual actors of very fossil-fuel dependent countries, and then a lot of the countries who are most impacted want more of kind of a ban approach. And the US has been kind of in the middle and not really making a statement one way or the other. But I was just wondering if you follow the treaty, and do you have thoughts on its trajectory thus far?

Timnit Kefela

I have a lot of feelings about the global plastic treaty. I'm thankful that what I hope can be a legal binding instrument is being developed, but I'm not particularly fond of how the science, independent science, particularly as well as the communities impacted by plastic pollution are not being centered and supported by certain regional parties that are fossil-fuel dependent economies who typically carry a lot of power in these negotiations, in part, also because of heavy industry influence, also influencing their perspective and stance. We need a plastic production cap, inclusive of the additives used in them. We produce way more than we need, and reduction in production is crucial to limit its impact on human and environmental health. We need transparency about the plastics produced, the fate of the products developed as substitutes should be considered, as well as the implementation of waste management strategies that are still environmentally detrimental and just displacing the problem, should be rejected, like incineration, for example. Similarly, like many others, I strongly believe that the treaty should also advocate for safer and more sustainable livelihoods for the workers that are involved in the plastic supply chain. I also firmly believe that, and I will hone on this again, that community voices and science should be integral –like it should be the soul– of how this global plastic treaty shapes up. Advanced chemical recycling may sound attractive in concept, but it's not successfully scalable right now, and we need to act now. In addition requiring such infrastructure and keeping it business as usual, will foster inequity, because infrastructure is power and more affluent nations will have access to these technologies, whilst the rest of the world will not, which is wildly unfair, because several nations bear the burden of Western nations plastic waste and do not have the infrastructure or management strategies in order to deal with it. So definitely, I think technologies like that should not be what we see as the solution to this issue, because we cannot wait. It's something that we need to act on right now, and we need to recognize how inequity plays a role in who will have access to a healthy environment and who will not.

Brian Bienkowski

The parallels between this crisis and the climate crisis to me, and I know there we mentioned how they're already intertwined, but there's just so many parallels with chemical recycling is kind of like the carbon capture on the climate side, where it's like, what will allow us to keep doing the thing but make it seem like we're we're avoiding the worst of the outputs, the waste at the end of the life cycle, and it's, again, it is the same voices. So make your own conclusions as to those voices and what their what their goals are. So Timnit, thank you so much for all of this has been such a fun call. I have to ask you, when you research this, I think people probably turn to you. Well, I'm going to turn to you right now. How do you handle your own plastic use and try to avoid microplastics? And what would you recommend to somebody who wants to do the right thing?

Timnit Kefela

Yeah, so I am privileged enough to try and limit my plastic use as much as possible. Am I plastic free? No, it's not entirely accessible for me. I think some suggestions are like, avoid pre-made or pre-processed foods, right? I can't necessarily do that sometimes, because I live with chronic migraines, and so when I'm in a lot of pain and I need to eat, I cannot cook, right? So being reliant on that is really necessary for my livelihood in those moments, I do try to limit how much plastic I consume, and often repurpose and reuse materials in my life, so many a pasta sauce jar are now spice jars or, you know, vessels for my plant clippings, or their makeshift, you know, iced-coffee cups and stuff. So I tend to like reuse a lot of non plastic materials that I end up having in my home. Any plastic bags that I do receive get multiple uses prior to disposal, so they will be trash bags many a time until they're ready not to be trash bags, right? I carry a collapsible bag and decline plastic bags at the store. I try to use reusables as much as possible, but I think it's really important to note, as I've mentioned, that I can trust the water that comes from my tap. So I can use a reusable water bottle. I bring reusable mugs with me as well as cutlery my backpack. So if I ever have to go to a coffee shop, that's where I get my coffee. To avoid having, like, plastic cups, I try to use glass lunch containers, which I find in the thrift store. Thrift stores are really good to find, like, a lot of non-plastic items at a fraction of the cost of what you would buy if you went to an actual department store. I run an air purifier in my home to limit atmospheric microplastics. I A lot of the stuff is just reuse. That's like, really, how I try to avoid I only consume when I absolutely need to. If there's something that I can't get past that I already don't have, that's when I'm probably going to purchase something. I grew up in a household where things were used until they could not be anymore. So I have gone into the freezer multiple times thinking I was going to find ice cream, but I found stew. So growing up in such a household where you know that happens quite a bit, as well as like, your clothing then eventually becomes rags, because everything needs to have a use has really, like influenced the practices I keep in my life still. And I would love to give a special shout out to my mother, who really practices sustainability in this beautiful way, and has taught me to do so as well. And so I think the my suggestion for people is do what you can do what is accessible to you, and that could be a really good way and a really even though it may feel small, it's still a fairly significant way, and I hope helps you have agency over understanding that you're limiting the amount of microplastics in your life.

Brian Bienkowski

Thank you so much for that, and I think it's a lot of again, something like carrying cutlery in your bag is just a small step. It's just but it's just reframing our mind a little bit about how we're interacting with the world. And I should have, on the front end of that question, said that, at least – this is my opinion – that you know too much is put upon the individual in this conversation, and that as we've discussed, and as you've so eloquently articulated, this is a problem on a global scale, with major industries at the heart of it who are trying to keep this crisis alive. So I did want to give people kind of what you can do in your own life, but I do want to acknowledge the fact that we should not be blaming ourselves. A lot of this is a lot of us just don't have a choice in the matter to live plastic free. So before we get to some fun question, what are you optimistic about?

Timnit Kefela

I'm optimistic that we can get this right. I think in the midst of all of this despair around plastic pollution, there needs to be hope that we have this opportunity to get it right, be it through a plastics treaty, governmental and industry commitment for the accountability for plastic production and waste and their associated chemicals, community voices being valued as expertise in coming up with initiatives and solutions, universally-designed substitutions that do not cause environmental and health detriment and challenges the paradigm that we are inherently wasteful human beings, right? I think, I think I'm also optimistic that we, a lot of actors, will essentially engage and take a lot of humility when it comes to this, because it's really important to recognize that this is our shared planet. A lot of us are already feeling the impact, and who's to say that those who don't won't feel it eventually. I often think about a lot of Black feminists and what they say being that we cannot heal in isolation, and that it requires us taking timely action and willing parties to acknowledge the bottom line that this isn't really about money. This is really about all of us and ensuring that we have a livable planet. So I truly, truly hope that, and I'm optimistic that we can get this right. It just really takes a lot of humility on a lot of our parts and learning to dissenter a lot of the loudest voices in the room in order to truly have a resilient planet, a resilient planet that isn't necessarily dependent on plastic or vulnerable to the impacts and detriment of plastic.

Brian Bienkowski

Well, thank you so much for that. I think that's a really nice way to end a serious part of this conversation. I really like ending on a high note, because I'll tell you what, the plastic stuff can really, really seem overwhelming. So thank you for a little dose of optimism at the end there. So these last these next three questions, you can answer just one word or a phrase, just a way for people to get to know you a little bit. What was your best summer job growing up:

Timnit Kefela

camp counselor

Brian Bienkowski

What is something you've always wanted to try but you haven't

Timnit Kefela

write a children's book.

Brian Bienkowski

You need to do that. What was your first concert

Timnit Kefela

Fall Out Boy.

Brian Bienkowski

All right, all right. I think my little sister, think my little sister, you might be the same age as her, she, I think that might have been one of her first shows, too. That is very cool. And what was the what was the last book you read for fun? You don't have to just confine yourself to a word or a phrase here.

Timnit Kefela

um, I two books, I will say, because I tend to always read concurrently with things. So I'd say the last two books that I read were, it's a memoir by Farah Naz Rishi, called "Sorry for the inconvenience." And I'm a really big fan of poetry. So I recently was also reading a collection by Lucille Clifton, a phenomenal Black poet, love love her so much, called "How to carry water." So those are the two that I've been reading. I last read for fun. Excellent.

Brian Bienkowski

I don't know if we've had poetry mentioned in the last book. I'd have to, I'd need to do a compilation of these at some point, because so many people have mentioned so many really cool books. But that might have been our first poetry mentioned. So thank you so much for that. And Timnit, thank you for just being in this program, and your work is so near and dear to me and our work over here. So I'm just really excited to have you, and I hope we have you on again soon.

Timnit Kefela

Thank you so much. Thanks for having me.

Plastic chemicals linked to $249 billion in US health care costs in just one year, study finds

By contributing to the development of chronic disease and death, a group of hormone-disruptive plastic chemicals is costing the US health care system billions — over $249 billion in 2018 alone, a new study found.

“Plastic will overwhelm us:” Scientists say health should be the core of global plastic treaty

United Nations’ draft treaty pays “lip service” to the known science, according to the group of international scientists who drafted an alternative health-focused treaty.

More than 20 international scientists put forth a plan today to encourage world leaders to put human health at the center of global plastic treaty negotiations taking place this week in Nairobi, Kenya.

The plan, dubbed the Health Scientists' Global Plastic Treaty by its proponents, comes as negotiators from about 175 countries — along with industry representatives, environmentalists and others — meet through Nov. 19 to advance a treaty to end global plastic pollution. The Nairobi gathering is the third of five such meetings. The plan is to complete negotiations by the end of 2024 and have the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) develop the first international treaty tackling plastic on land and in bodies of water.

The Health Scientists’ Global Plastic Treaty was led by the Plastic Health Council — a group of scientists that research the human health impacts of plastics. Pete Myers, one of the signees and members of the Plastic Health Council, is the chief scientist at Environmental Health Sciences, which publishes EHN.org. The alternative treaty outlines both short-term and long-term goals that would ensure a health-protective global treaty.

Short-term goals include:

- Stopping any consideration of chemical recycling

- Eliminating subsidies to plastic manufacturers

- Reducing single use plastic production by 50% by 2035

- Reducing virgin plastic production by 70% by 2024

- Banning the sale of all products with unnecessary plastic by 2030.

Long-term goals include stopping use of micro-and nano-plastics except in medical settings, eliminating all chemicals of concern in plastics and funding safe, sustainable plastic replacements.

“We desperately need a global plastics treaty that uses the irrefutable evidence from the litany of peer-reviewed research reports as a catalyst for real action,” Sian Sutherland, co-founder of A Plastic Planet and the Plastic Health Council, said in a statement. “What will it take for global policymakers to resist the intense lobbying from big oil and mandate safer materials and chemicals that do not infect our planet and our children?”

Delegates at the plastic treaty negotiations in Nairobi.

Credit: UNEP

Last September, UNEP released a “Zero Draft” of a potential treaty agreement, which does include some proposals to limit or ban some concerning plastic chemicals. The scientist’s treaty released today called the Zero Draft “well-intentioned” but that it “falls far short of what is needed to ensure the health of humans, wildlife and ecosystems.”

Whether — and how much — the treaty should regulate the chemicals in plastic production is a point of contention. Thousands of chemicals found in plastics — such as PCBs, phthalates, BPA and PFAS — are linked to health effects in humans, from the immune system to the brain to the endocrine system. Recent research of 1,500 plastic chemicals found fewer than 30% have been tested for human health impacts.

Related: Pete Myers' discusses the "Health Scientists' Global Plastic Treaty"

“Most people assume that materials are thoroughly tested before they are put on the market, but for plastics this is not the case,” the scientists wrote in their draft treaty. “Plastics have largely escaped regulatory scrutiny for over 100 years.”

Countries and other negotiators also remain at odds over whether there should be production caps or more of a focus on recycling and a plastic “circular economy.” A treaty that limits production would impact oil, gas and petrochemical interests.

While only about 9% of plastic is recycled, recycling plastics can release toxic chemical additives.

Promoting chemical recycling “would be the worst outcome the Treaty could endorse for managing plastic waste,” the scientists wrote.

“Plastic recycling has been touted as a solution to the plastics pollution crisis, but toxic chemicals in plastics complicate their reuse and disposal and hinder plastic recycling,” said Bethanie Carney Almroth, a signee to the Health Scientists’ Global Plastics Treaty and a researcher at the University of Gothenburg in Göteborg, Sweden, in a statement.

“Numerous studies show that hazardous chemicals can accumulate even in relatively close-loop plastic recycling systems,” she added. “We need to rapidly phase-out plastic chemicals that can cause harm to human health and the environment.”

The last plastic treaty meeting was in June and was hampered by delays and procedural debates, largely from countries that profit from fossil fuels — which are used to make most plastics — and plastic production such as China, India, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Prior to the Nairobi meeting, Saudi Arabia announced a coalition with Russia, Iran, Cuba, China and Bahrain called the Global Coalition for Plastics Sustainability, that will focus on plastic waste rather than production limits, according to Reuters.

On the other side of negotiations, more than 60 countries previously banded together to form the High Ambition Coalition with the goal of ending plastic pollution by 2040, with slowing production part of the solution.

The U.S. is not part of either coalition and has been criticized for initially favoring national commitments rather than legally binding global agreements. However, there are signals of a slight shift, as recent State Department statements have nodded to national plans being part of “universal obligations.”

The treaty is urgent as plastic production is on track to triple by 2060, an unsafe level for human health and the environment, according to an international panel of scientists.

“We must choose,” Myers said in a statement. “Will we smother the Earth and ourselves with toxic plastics? Or do we have the courage and foresight to stop the onslaught?”

See the full Health Scientists’ Global Plastic Treaty and follow treaty negotiation happenings at the UN Environment Programme page.

| BigStock Photo ID: 222758527 |

| Copyright: evgeny atamanenko |

Why you should stop using laundry pods right now

Save money and go easier on the planet with these tips and alternatives.

Julia Belluz: Scientists don't agree on what causes obesity, but they know what doesn't

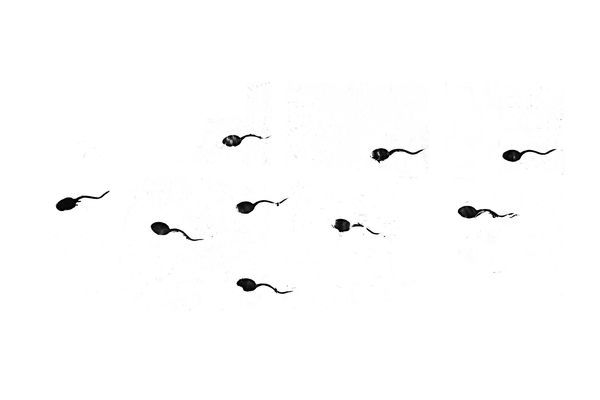

A new analysis shows a “crisis” of male reproductive health

Global average sperm count is declining at a quicker pace than previously known, chemical exposure is a suspected culprit.

For years, scientists across the world have gathered evidence showing declines in sperm quality. Now, new research compiling the results of those studies has found that sperm count has dropped dramatically around the world, and the rate of decline is accelerating.

In a new analysis, researchers at Mount Sinai Medical Center, the University of Copenhagen, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, among others, found that sperm count globally dropped by more than half between 1973 and 2018, and that the decline is accelerating: Since 1972, sperm count has dropped by about 1% each year. Since 2000, the annual decrease has been, on average, more than 2.6%.

The findings raise concerns that an increasing number of people will need assistance to reproduce, as well as concerns about the overall health of human society, since low sperm count is linked to higher rates of some diseases. And while scientists are still trying to tease out the reasons for the drop, chemical exposures, especially to pesticides, are a likely factor — and climate change may even play a role. Researchers are calling for urgent action to bolster more research into sperm count, determine the causes of the decline, and prevent further deterioration of male reproductive health.

“We have clear evidence that there is a crisis in male reproduction,” Hagai Levine, lead author on the study and an epidemiologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told EHN.

An “alarming” decline

The study builds on the team’s previous research, which showed a decline in sperm count in North America, Europe, Australia, and parts of Asia of 28.5% between 1973 and 2011. Adding data from 38 studies to the new analysis has made the case for sperm decline stronger, Shanna Swan, an author on the paper and a leading reproductive epidemiologist at Mount Sinai, told EHN. “It’s really alarming,” said Swan, who is also an adjunct scientist with Environmental Health Sciences, which publishes EHN.org.

Swan authored the book Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.

The research found that the average global sperm count in 2018 was 49 million per milliliter of semen. When a man’s sperm count drops below about 45 million per milliliter, his ability to cause a pregnancy starts dropping dramatically, said Swan. She said the results could mean that in the coming decades, large swaths of the global population of men could be subfertile or infertile, or could require assisted reproduction techniques, like in vitro fertilization (IVF), hormone treatment, or a technique called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), in which sperm are directly injected into an egg.

In addition to the drop in average sperm count, Levine said it was surprising that the rate of decline was accelerating, rather than slowing down. “Is there a tipping point, that once you cross, you get an even worse situation?” he said. “That’s something to really pay attention to.”

Overall, said Levine, the results indicate that “something is very wrong with our global modern environment.”

Sperm count is not only a reproductive concern, but an indicator for other health problems in men, and is used as a predictor for male longevity. Men with poor sperm count tend to have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers and even death, Michael Eisenberg, a professor of urology at Stanford University who was not involved in the research, told EHN. “This decline in sperm count could also suggest other health concerns,” he said.

A 2016 study authored by Eisenberg found that diabetes and other diseases were associated with lower reproductive health. However, said Eisenberg, the reason why overall health is linked to sperm quality is still unknown.

Eisenberg said the new study on sperm count decline is a “powerful addition” to previous evidence that sperm count across the globe has declined.

Reasons for the trend

Though the reasons for the drop were not discussed in the paper, scientists have known for decades that certain environmental factors, like exposures to pesticides (such as atrazine, alachlor, and diazinon) and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals, like phthalates, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), can have impacts on reproductive health. Nearly 20 years ago, for example, Swan and other researchers published an analysis of research into links between pesticide exposure and sperm quality, and found that 79% of studies indicated a decrease in sperm quality among those exposed to the chemicals. Diet, activity level, and stress may also play a role.

Swan and Levine said exposures to chemicals in the environment and other factors likely all play a substantial role in the sperm count trend. And, the risk factors are related; for example, obesity is a risk factor for lower quality sperm, but certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals — which interfere with how hormones work — are thought to contribute to obesity, as well. Diet is hard to decouple from chemical exposures, too, since pesticide residues linger on much of the food we eat.

Related: Count Down — The infertility crisis

Additionally, both Swan and Levine said climate change could be a factor, both due to climate-related stress and actual fluctuations in temperature, since heat waves are linked to decreases in sperm quality.

Prenatal exposure may be a contributor, too. Chemical exposures during the male “programming window,” when reproductive traits are formed in utero, have an outsized effect on sperm quality later in life, said Swan. For example, she said, when a man smokes — a known endocrine-disrupting activity — he lowers his sperm count by about 20%. When a male is born to a woman who smokes, his sperm count is reduced by about 50%. Those effects may last for generations before subsequent children and grandchildren return to normal sperm counts.

Protecting reproductive health

Levine is optimistic that scientists and policymakers can reverse the trend if they can determine the causes. Swan pointed to the sharp drop in cigarette smoking in the past 50 years as evidence that widespread lifestyle changes are possible, and said that any large-scale adoption of healthier habits, like better diets and more physical activity, can help improve reproductive health.

Making individual lifestyle changes like choosing organic, pesticide-free produce and staying away from certain plastics and chemical products can help lower a person’s exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, too. However, doing so can be difficult, especially for disadvantaged populations with less access to fresh foods, higher environmental exposures, and fewer means to purchase safer, non-toxic household goods.

To truly tackle the problem, though, much more research is needed, said Swan. One thing she’d like to see would be better tracking of sperm count, similar to how the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks obesity. Levine also said better surveillance tools will be crucial to understanding the problem more deeply.

Once humankind “defines a problem and puts our resources and mind into it, we find solutions that we could not have thought about when we started,” said Levine. “It's always theoretically reversible.”