Peter Dykstra: Two enduring signs of hope

Can the world come together to arrest climate change and turn back other environmental threats? Two successful treaties can show the way.

It was 1957. I was born. Elizabeth had been queen for four years. Elvis had been king for one, give or take.

For the world's scientists, '57 was the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The IGY gave special focus to the science of Antarctica, prompting an unprecedented wave of interest in the Frozen Continent.

But 1957 was also a peak year for the Cold War, and Antarctica's potential mineral wealth and other resources were still fair game for anyone.

Two years later, Cold War be damned. The Soviets, Americans and 10 more countries active in Antarctic exploration signed the Antarctic Treaty. Since then, 41 more nations have signed on. The treaty took effect in 1961, and for nearly 60 years, the world has agreed to protect a continent.

Oil, gas and coal deposits are known to exist beneath the Antarctic ice. But fossil fuel recovery is unrealistic – unless oil, gas, and coal lead the way to someday liberating the continent from its ice cover. Valuable metals may exist there, but firm evidence of any sizeable mineral wealth doesn't yet exist.

But in the 50s, diplomats and scientists posted a durable warning that the Antarctic would stay off limits to corporate and government pressure to tap into it all: Not only an undrilled and unmined free zone, but offshore fisheries that are among the least exploited on earth.

Nations have gone to war over much less than Antarctica may have to offer. But the Treaty has kept the peace for more than half a century.

A rare, hole-some agreement

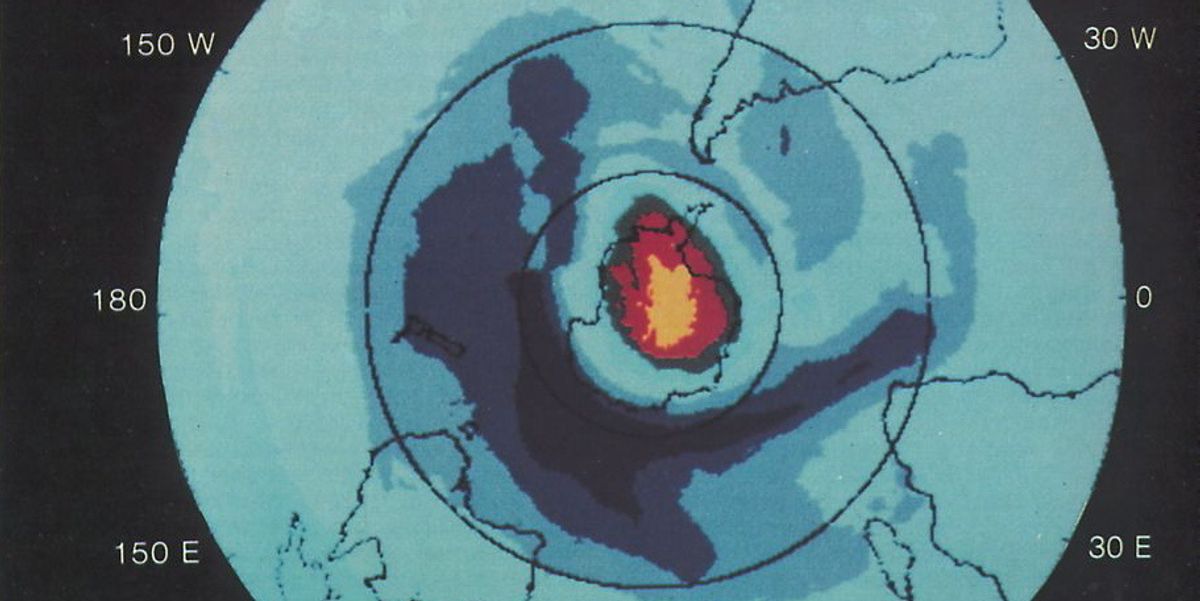

At an August 1985 meeting in Prague, atmospheric scientist Pawan Bhartia presented this satellite-based image that revealed for the first time the size and magnitude of the Antarctic ozone hole. (NASA)

With science in the unfamiliar role of trumping exploitation on the continent, more Antarctic research led to an alarming discovery: Manmade chemicals, notably chlorofluorocarbons (CFC's) used as refrigerants and propellants, were eating holes in the stratospheric ozone layer that protects the Earth from the sun's more harmful rays.

An expanding ozone "hole" over the South Pole, and a smaller one in the Arctic, threatened to impact plant and animal life by allowing ultraviolet solar radiation to reach the earth. Three scientists who were key to connecting the dots – Sherwood Rowland, Mario Molina and Paul Crutzen – began studying the effects of CFC's in 1973, and later shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

Concern grew throughout the 1980's as more research confirmed that the ozone holes were growing, and the ozone layer over temperate parts of the planet was thinning. Scientists, environmental advocates and industry all played their familiar roles, sounding the alarm, or drawing heavily on the doubt and denial playbooks.

But three world leaders defied assumptions and stereotypes, playing key roles in forging a global agreement to protect the ozone layer: Ronald Reagan, whose government normally fought environmental regulation; his conservative soulmate, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher; and Canadian PM Brian Mulroney, who lobbied to become the host nation for a crucial meeting.

In 1987, the Montreal Protocol was signed, phasing out CFC's and other ozone depleting chemicals. It's now ratified by 197 nations and the EU. By the mid-2000's, scientists confirmed a gradual closing of the ozone holes, with a return to normal levels by 2100.

It's hard to imagine the contemporary conservative heirs of Reagan, Thatcher and Mulroney showing similar leadership. Trump's anti-regulatory rampage included a departure from the Paris climate accord; the UK's Brexit quagmire was partially inspired by disdain for European Union environmental policy; and Stephen Harper, the most recent Canadian conservative PM, directed a thorough purge of government environmental science.

But the urgent need for action on climate change, biodiversity, the nearly-unthinkable collection of plastic in our oceans, and other challenges may someday turn the corner for Tea Partiers and Brexiteers.

The Antarctic Treaty and the Montreal Protocol are real-life examples of how it can be done.