LISTEN: Kristina Marusic discusses the "Fractured" investigation

"Once they had the results of our study [families] felt like they had proof that these chemicals are in their air, their water, and making their way into their bodies."

Environmental Health News reporter Kristina Marusic gives the story behind "Fractured," an investigation of fracking pollution in western Pennsylvania.

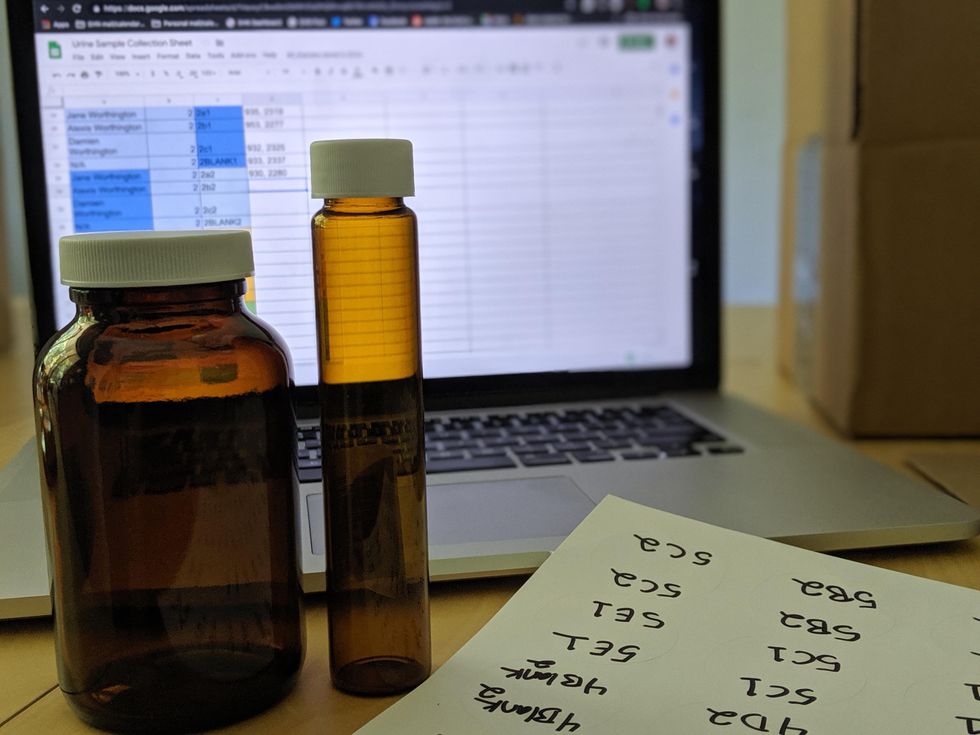

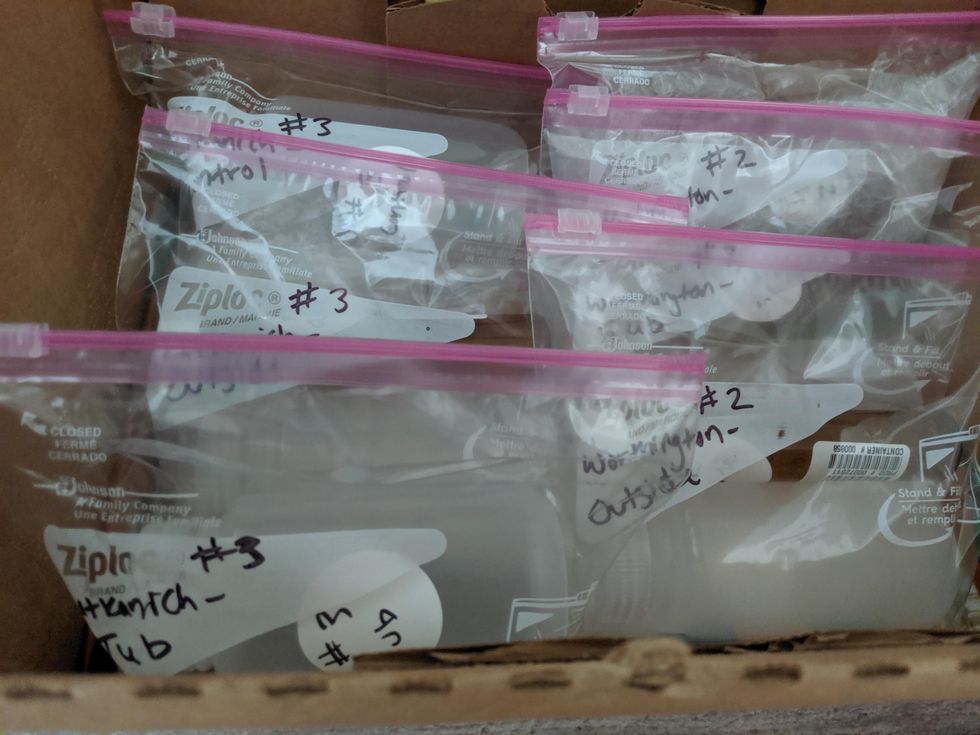

The series, published this week, reveals alarming evidence of toxic industrial chemicals linked to drilling operations in the urine of families living near fracking operations. Marusic spearheaded the investigation by collecting urine, air, and water samples from five southwestern Pennsylvania households. Her work represents the first time families in western Pennsylvania have been tested for exposure to chemicals emitted from fracking operations.

In addition to the pollution exposure, the series exposed a regulatory system that favors oil and gas development at the expense of residents' mental, physical, and social well-being.

"I hope these families will be able to use this data to better advocate for their own health with their political representatives, and their doctors, and their community leaders," she said.

Read the four-part series and see the study results at EHN.org/fractured. Follow the conversation and fallout from the investigation on Twitter at #fracturedUSA.

Listen to Marusic discuss the series below.

Have you been impacted by fracking? We want to hear from you. Fill out our fracking impact survey and we'll be in touch.