Op-ed: Beignets, coffee and petrochemicals

Though Black History Month is coming to an end, let’s continue to amplify the voices of fenceline communities fighting toxic pollution.

Since I was a young Black girl, Black History Month has always been an uplifting yet somber experience for my family.

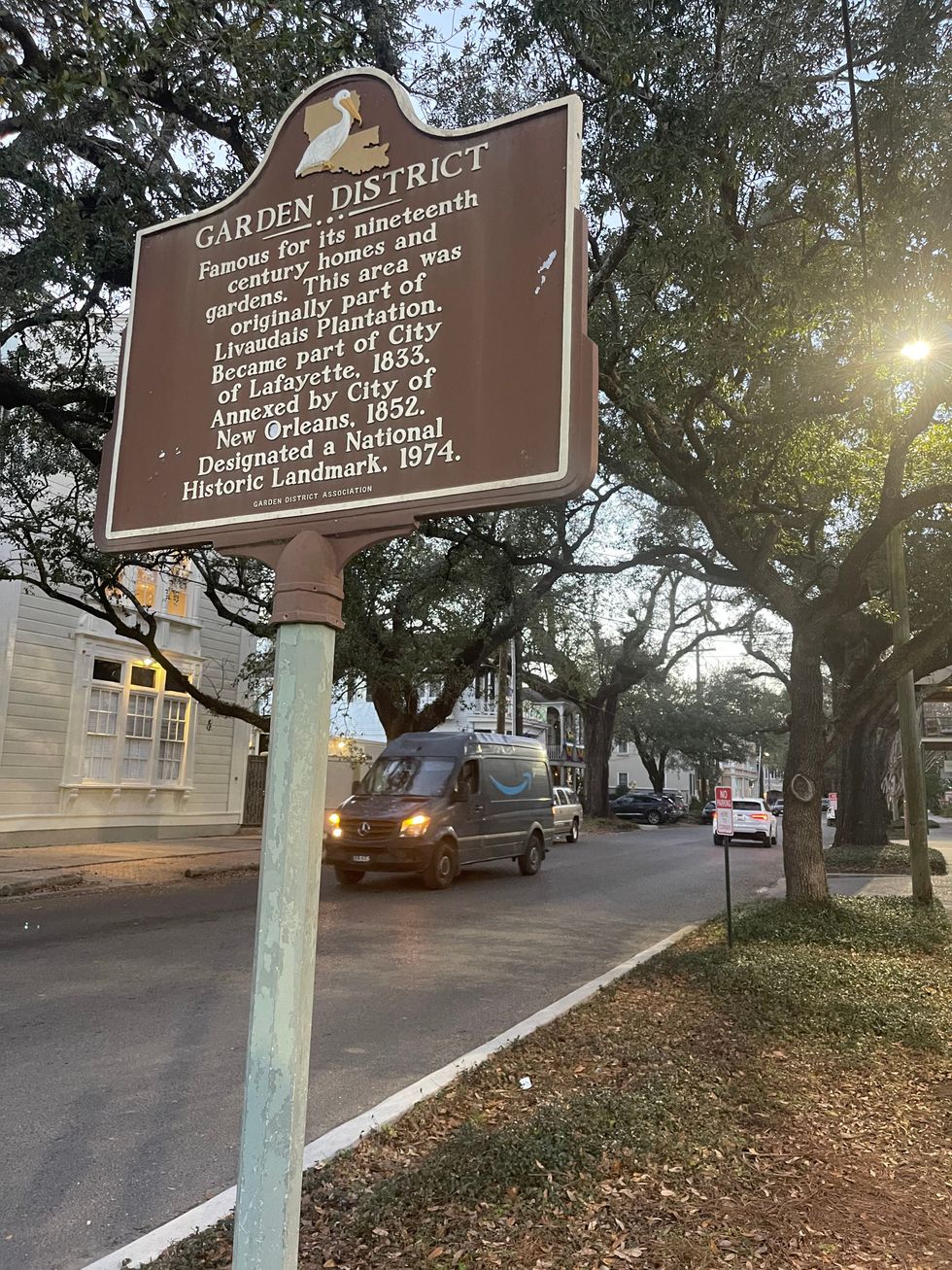

We focused on honoring our culture, contributions and triumphs, while identifying a path to a brighter tomorrow for African Americans. I had a similar vibe during a recent visit to New Orleans for a media briefing on plastics, petrochemicals and environmental justice. Hosted by Beyond Plastics, The Descendants Project and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, the sessions were structured around protecting African American communities, preserving cultural resources, understanding the nationwide petrochemical build-out and amplifying the evidence of toxic pollution around fenceline communities such as “Cancer Alley.”

Polluted parishes

Due to high levels of pollution and associated clusters of cancers, the 85-mile stretch of land along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is often referred to as Cancer Alley. However, many locals are not aware of that name, which I found out in casual conversation with hotel staff in the French Quarter District.

While the science is clear on the increased risk of cancer in New Orleans associated with chemical plants, there is a need to amplify these findings. It’s crucial for the affected residents to be well-informed within the majority-Black areas of St. John the Baptist Parish and St. James Parish.

While many of the petrochemical facilities say their jobs create an economic win for the city, community activists who attended the briefing disagreed, saying the facilities have a history of outsourcing labor except for lower wage jobs. Concerned citizens believe they are bearing the environmental consequences of petrochemical and petroleum plants.

Which brings me to the Cancer Alley bus tour where we visited historical landmarks, such as the catfish capital of Lac des Allemands, a 12,000-acre lake for fishing. We passed by above-ground coffins at cemeteries, and visited the Whitney Plantation. I’ve never knowingly set foot on a plantation. As the bus hobbled over the rocky entrance, I felt nauseous looking at the sign. I’ve seen some gritty moments growing up in Chicago. But nothing compares to the past tragedy that my enslaved ancestors endured at that sugarcane plantation.

While this ugly past mingles with ongoing pollution from numerous sources, it would be remiss not to recognize the region’s vibrant culture, food and nightlife.

Beignets and coffee

I’ve had beignets at Los Angeles cafes, but nothing compares to Café du Monde on Decatur Street in the French Quarter. A lightly fried, crispy pastry sprinkled with powdered sugar pairs perfectly with the cafe’s chicory coffee. In the context of Black history, Café du Monde was one of the first restaurants to integrate when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964. Many Southern venues refused to adopt, or begrudgingly served Black customers by creating separate menus with higher prices or posting signs to announce profits earned from Blacks would be used to fund racist organizations. I think about how my mother at my age now would not have been able to indulge in the beignets and café au lait as I did with my coworkers. Although present times are brighter, the petrochemical industry is a growing culprit of environmental racism in New Orleans.

People over pollution

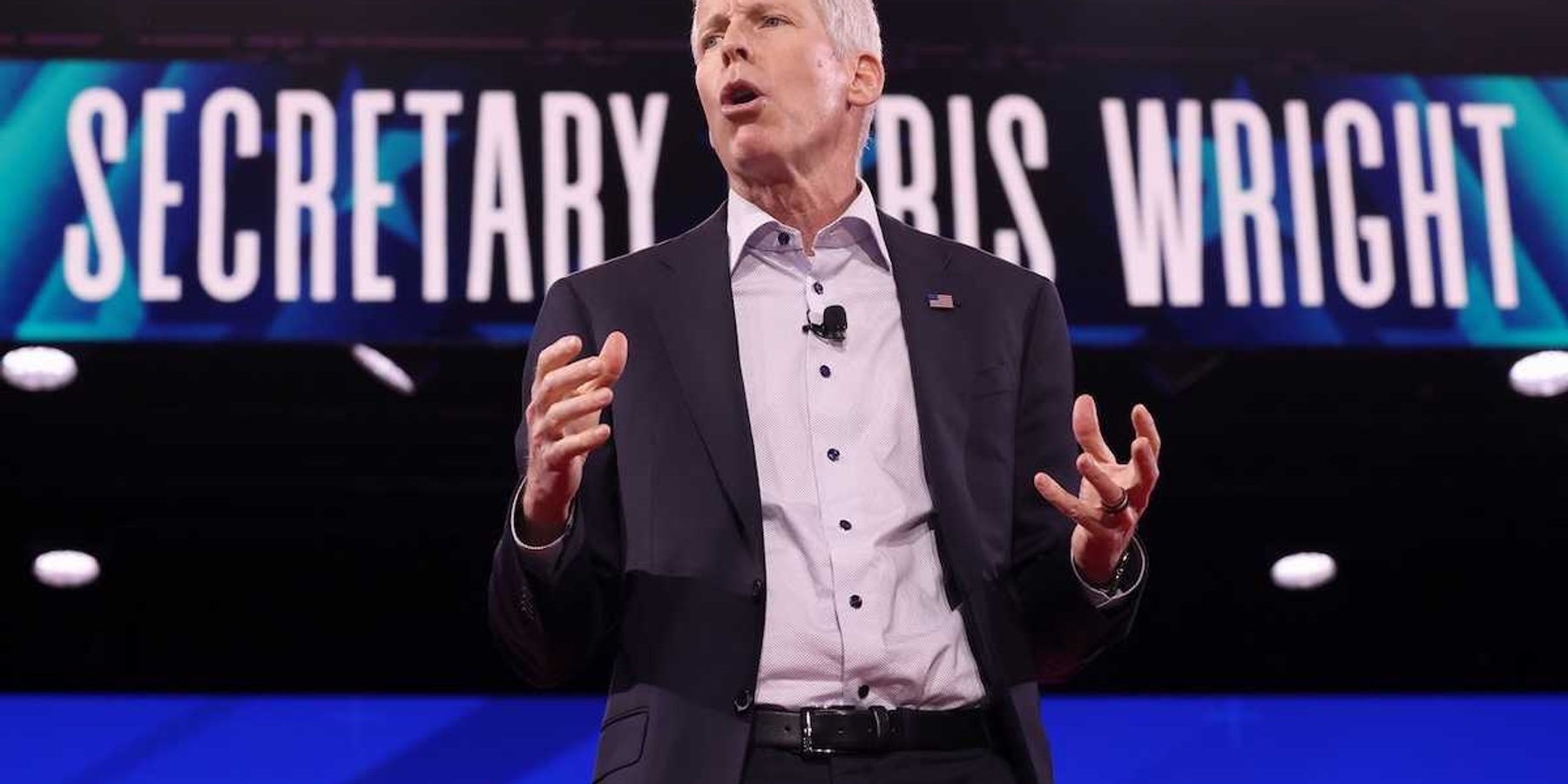

In an effort to protect these communities, former mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg, launched the campaign Beyond Petrochemicals to hinder new plants from opening. During the media briefing, we also gained insights about the affected elementary schools and churches that are working in the trenches to advocate for the health of their congregation. Dr. Kim Terrell, research scientist and director of Community Engagement at Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, provided a brief overview of The United Church of Christ’s report on toxic pollution. The report examined the high level of toxic exposures from plants near predominately Black schools.

Power boulevard

New Orleans has a culture that doesn’t allow the good, the bad and the ugly of history to be rewritten or forgotten.. As I headed to the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, driving along the 10 freeway, I was thinking about the lines of power in the city, who runs them and how can that power be shifted. Minutes later, I saw the green highway sign, Power Blvd., located in the town of Metairie. According to a local historian with Louisiana Bucket Brigade, the boulevard was likely named due to a large power transmission line that stretches alongside I-10 to the drainage canal in District 1.

When I returned home, my kids were excited about their Mardi Gras t-shirts and crocodile stuffed toys. The next day, I was at my son’s high school basketball game, telling a group of parents that I had just returned from New Orleans. One of the father’s mentioned that he went to Grambling State University, a historically Black college located in northern Louisiana. After sharing my adoration for the city, he responded, “But how ‘bout that air quality?”

There is a moral urgency to the toxic pollution crisis in environmental justice communities. As a nation, we have a duty to care for vulnerable populations. Locals take great pride in their city. Many residents do not leave because they cannot afford to. Additionally, family legacies have been established and they want to continue residing in the place that generations of their families have known as home for years. Many community activists who can afford to relocate to other states remain in Louisiana to fight the good fight.

As part of our commitment to environmental justice reporting, Environmental Health Sciences will ramp up our coverage of these communities and others like it who carry the burden of our fossil fuel and plastic addictions. Watch this space.

New Orleans owes me nothing, but the city is owed so much more from our nation.

Angela Marie Hutchinson serves as the engagement director for Environmental Health Sciences. Recognized by Congress as a media and arts trailblazer, Hutchinson is also an author, TV and film producer. She resides in Los Angeles with her husband and three children.