Peatlands keep a lot of carbon out of Earth’s atmosphere, but that could end with warming and development

Permafrost degradation, warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and drought are causing peatlands to lose stored carbon.

Peatlands are a type of wetland where dead plant material doesn't fully decompose because it's too soggy.

In these ecosystems, peat builds up as spongy dark soil that's sometimes referred to as sod or turf. Over thousands of years, yards-thick layers of peat accumulate and trap huge amounts of carbon, helping to cool the climate on a global scale.

But that might not be true for much longer. Warming temperatures and human actions, such as draining bogs and converting them for agriculture, threaten to turn the world's peatlands from carbon reservoirs to carbon sources.

In a newly published study, our multidisciplinary team of 70 scientists from around the world analyzed existing research and surveyed 44 leading experts to identify factors that could change peatlands' carbon balance now and in the future. We found that permafrost degradation, warming temperatures, rising sea levels and drought are causing many peatlands around the world to lose some of their stored carbon. This is in addition to rapid degradation caused by human activity.

And unless steps are taken to protect peatlands, carbon loss could accelerate.

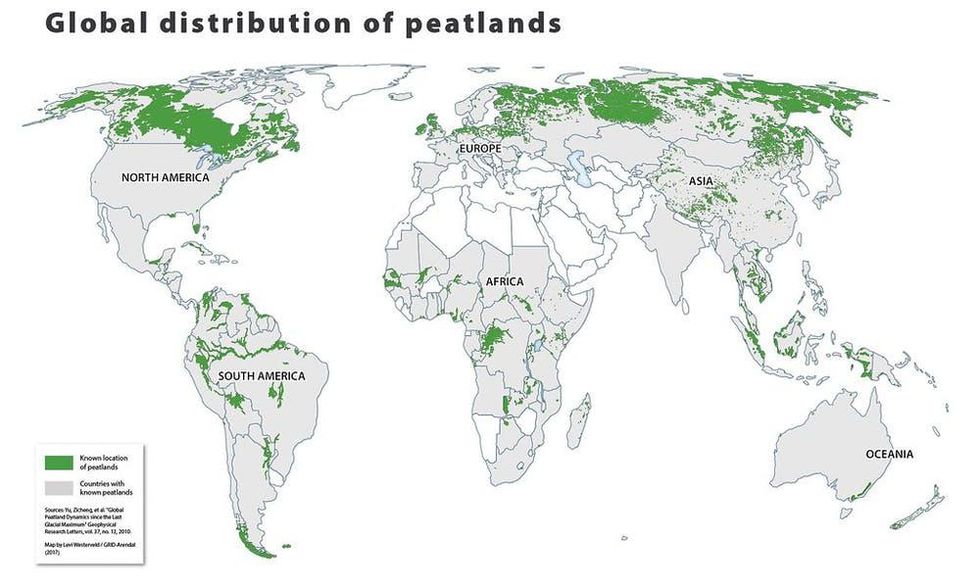

Peatlands are found in an estimated 180 countries. Many of them have not been recognized and are not yet properly mapped. (Credit: Levi Westerveld/GRID-Arendal)

From carbon sink to carbon source

Although they only occupy 3 percent of the global land area, peatlands contain about 25 percent of global soil carbon — twice as much as the world's forests. Peatlands exist on every continent, even in Antarctica. In the U.S. they are found in many states, including Maine, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin. These ecosystems form where partially decayed organic matter accumulates in cold soil that is nearly always wet, which dramatically slows decomposition.

But now climate change is altering those conditions. For example, in many regions of the Arctic, rapid permafrost thawing promotes microbial activity that releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. These microbes feed off carbon-rich peats that were once frozen.

Massive peatland fires also contribute. Recent wildfires like those in Russia are known to release as much carbon in a few months as total human carbon dioxide emissions in an entire year. And these fires are especially tricky to put out. Embers within the dense organic matter can reignite many months or even years later.

Human activities are also increasing greenhouse gas releases from these carbon-rich ecosystems. In the United Kingdom, for example, extracting peat for use in gardening has caused peatlands to emit an estimated 16 million tons of carbon every year—roughly equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions from more than 12 million cars.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, as fertile land becomes increasingly scarce, peatlands are being burned, drained, and repurposed. Already, most peatlands in Indonesia have been destroyed in order to build palm oil plantations. The World Resources Institute estimates that in Indonesia and Malaysia, peatland draining results in total annual emissions equal to those of nearly 70 coal plants. These activities also endanger vulnerable animal populations, such as orangutans and various species of freshwater fish. Peatland degradation due to human activity accounts for 5-10 percent of annual carbon dioxide emissions from human activity, despite these zones' tiny geographic footprint.

Quantifying peatland carbon

Predicting how much carbon will be released from peatlands worldwide is hard to do, especially because no models can adequately represent these ecosystems and the many factors that influence their carbon balance.

Peatlands are not included in most earth system models that scientists use to make future climate change projections. There is a long-held view that peatlands are minor players in the global carbon cycle on a year-to-year basis, but our study and many others show that climate change and human intervention are making these ecosystems very dynamic. Our study highlights the need to integrate peatlands into these models; we also hope it can help direct new research.

Even though models are not ready, decisions need to be made now about how to manage peatlands. That's why we surveyed experts as a first step towards predicting the fate of peat carbon worldwide.

Based on their responses, we estimate that 100 billion tons of carbon could be emitted from peatlands by 2100 – am amount equivalent to about 10 years of emissions from all human activities, including burning fossil fuels and clearing forests. The experts we consulted have not reached a consensus, and our estimate is highly uncertain: Net changes in peat carbon over the next 80 years could range from a gain of 103 billion tons to a loss of 360 billion tons.

Not every region will be affected the same way. High-latitude peatlands might see an increase in carbon storage under a warming climate because of increased plant growth and greater peat accumulation. Tropical peats, on the other hand, are more likely to dry out and burn due to warming temperatures and human activity. These factors and human choices about peatland use will affect whether these areas become carbon sources or sinks in the future.

Overall, our results suggest that carbon releases will surpass carbon gains in the coming years, primarily because of human impacts in tropical peatlands. This switch from carbon sink to carbon source will feed a positive feedback loop, with peatlands releasing carbon that makes Earth's climate warmer, which makes peatlands release more carbon, and so on.

Despite the uncertainty in our findings, we believe our results show that peatlands should be included in climate models, and that nations should take steps to preserve them.

Toward sustainable use

A balance must be achieved between wise peatland use and local economic needs. Given how much carbon peatlands hold and how vulnerable they are, many surveyed experts believe people soon will adopt more sustainable practices for managing them. But others are not so optimistic. In regions such as the Amazon and the Congo basins, where large peatland complexes were recently discovered, it is critical to take action to preserve them.

Peatlands should also be considered in integrated assessment models that researchers use to understand climate change impacts and options for mitigating them. Models that project future socioeconomic change and carbon emission pathways could help develop incentives such as peatland carbon pricing and sustainable use practices. This would change the way these ecosystems are valued and managed.

The first step, however, is to raise awareness around the world of this precious natural resource and the consequences of continuing to exploit it.

Julie Loisel is an assistant professor of geography at Texas A&M University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Banner photo credit: David Stanley/flickr