Sewage adds to Detroit's headache

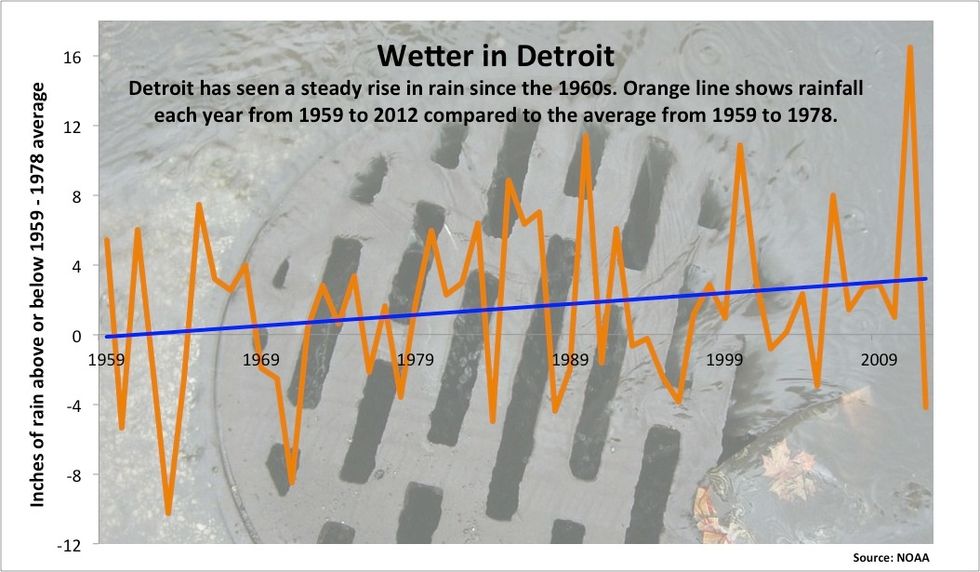

Detroit is already failing its citizens. Climate change is compounding the woe. With downpours up 45 percent in the past 50 years, the city's outdated sewer system can't handle the flow.

DETROIT – The spring rains came bursting down this year, and down again and yet again. And in this bankrupt city, the aging sewage system couldn't keep up – just like it couldn't in 2011 and 2009.

So on a Thursday morning in April, Detroit's wastewater managers opened 11 pipes and sent 110 million gallons of raw sewage spewing into the Detroit River. They poured another 3.5 million into the nearby Rouge River.

There was a brief letup. Then six days later came the clouds and the rain. And another 75 million gallons of sewage tumbled into the Detroit River.

"That week, April 11 to about the 18th, we were running at about 1.5 billion gallons a day" at the wastewater treatment plant, said Dan Schechter, superintendent of engineering at the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, at his desk at the Detroit Wastewater Treatment Plant on the city's industrial southwest side.

The plant can only treat 930 million gallons a day. Concrete basins designed for overflow can only hold so much – so the rivers receive the rest. Heavy flows get diverted to retention basins until the system can catch up. But when basins fill, the pipes to the rivers open.

A growing crisis

For Detroit, bankrupt and dealing with political and financial turmoil, this is a crisis: An aging, flood-prone sewer system sends raw sewage into the Detroit River during intense downpours. Such spewing can expose people who swim or paddle the river to disease-causing bacteria and viruses. The Detroit River also links the upper and lower Great Lakes, so its contamination affects the health of the region's entire watershed.There's little question the region is already dealing with the impacts of a changing climate. Rain from heavy, flood-causing storms has jumped 45 percent across the Midwest the past five decades, according to federal scientists. Greenhouse gases increase the energy in the atmosphere and tend to concentrate storms. Southeast Michigan, thanks to a quirk of atmospheric currents and geography, has been hard hit: Annual precipitation has increased 10 to 15 percent in and around Detroit the past 30 years.

In a city where services are beyond strained, climate change is compounding the woe.

"Without trying to sensationalize – it's like a slow (Hurricane) Katrina here," said Larissa Larsen, an associate professor at the University of Michigan and co author of a report on climate change vulnerability in Detroit by the Detroit Climate Action Collaborative. "Whether it's climate caused flooding, a serious blackout or extreme heat, I'm scared … especially for those vulnerable populations."

A combined sewer system means sewage and stormwater go to the same pipes. These systems are no longer built because when it rains hard it can lead to bacteria-tainted water overflowing. Still, about 800 U.S. communities – mostly in the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast and the Great Lakes region – are served by combined sewer systems, according to the EPA.

Detroit's is one of the oldest.

Relentless rain

Overhauling a combined sewer system costs billions. Detroit, saddled with a $330 million spending gap this year and almost $16 billion in long-term debt, is ill-prepared to undertake such an endeavor. The state appointed an emergency manager to take control of city finances in March, and the city declared bankruptcy on July 18.

Yet the rains keep coming. In the wettest year on record, 2011, Detroit spewed about 7 billion gallons of untreated sewage into the Rouge and Detroit rivers, according to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. An additional 25 billion gallons of partially treated sewage – where solids were removed but the water wasn't disinfected – poured into the rivers that year as well.

Things haven't let up. June was the ninth wettest month on record for southeast Michigan since 1874, according to the National Weather Service. The city released more than 2 billion gallons of partially treated sewage and 82 million gallons of diluted sewage into the Detroit River in June alone.

The city reported 55 combined sewer overflow discharges to the Detroit River in 2011, which means too much rain overwhelmed the system and partially treated or untreated wastewater discharged into river. There have been 31 discharges in 2013 so far.

Overflows can cause a number of problems. The water carries harmful E. coli bacteria, which can make people sick if exposed to the water.

The Detroit River empties into Lake Erie, which had its worst algae bloom ever in 2011. The bloom was due to a confluence of factors, including record farm runoff, but overflows from Detroit affect the entire Great Lakes basin, said Joel Brammeier, president of the Alliance for the Great Lakes, a nonprofit environmental organization.

"The 'dump sewage into the Great Lakes' approach to sanitation should have been left behind a long time ago," Brammeier said. "But policy and infrastructure haven't caught up."

And it's not just Detroit. Other large Midwest cities are facing the need for major infrastructure upgrades.

During the heavy rain year of 2011, Hammond, Ind.; Toledo, Ohio; Buffalo, N.Y.; Chicago and Cleveland – all saddled with aging combined sewer systems – each spewed more than a billion gallons of sewage into either the Great Lakes or a nearby watershed.

A year ago, fellow Great Lakes city, Duluth, Minn., experienced its worst flood ever: Up to 10 inches of rain fell over two days, causing massive sinkholes, damaging roads and bridges, flooding homes and killing 14 animals at the Lake Superior Zoo.

Nine counties in northeastern Minnesota were declared disaster areas. Damages were estimated at $108 million, and sewage overflowed in both Duluth and nearby towns.

No money

Detroit's woes are particularly compounded by a shrinking population. The nation's sixth largest metropolis three decades ago, with a population of 2 million, the city today has plunged to 18th, with just 700,000 people. Entire neighborhoods sit abandoned, the tax money gone. But the need for working pipes remains.

The city's wastewater system serves Detroit and 76 nearby communities – about 3 million people over 946 square miles. As pipes and other parts of the system age, the cost to maintain them increases, Schechter said. "Funding is a continual challenge for Detroit."

The infrastructure has already collapsed in certain parts of the city, said Nancy Love, an engineering professor at the University of Michigan. "When there is a big storm event there's a big flush – leaves, dirt, and stuff collect in the system from deteriorating parts of city."

It's unclear how much of the city's collection system is currently inactive, Schechter said.

But the city stopped street sweeping a few years ago because there's no money. "So now, when there's a big rain, we get more trash clogging up the system," he said. "That certainly doesn't help matters."

In a city that is more than 83 percent black and has a median household income 42 percent lower than the state, heat waves, flooding and other climate change challenges are an environmental justice issue, said Kimberly Hill Knott, a senior policy manager at Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice.

"It's a poor city and people are going to have to dip into their pockets to deal with climate change impacts," Knott said, referring to higher energy costs and taxes to help strengthen city infrastructure.

Fixing the problem

Fixing the problem isn't cheap, as other cities throughout the region have found.

Grand Rapids, 150 miles west of Detroit, spent two decades and roughly $240 million separating and upgrading its sewage and stormwater drains. The city relied on combined sewers built in the 1800s, until they started separating them in the 1990s.

The city's sewer system, which serves 272,000 people, is almost entirely separated now, said Mike Lunn, the manager of Grand Rapids' Environmental Services Department. The city used state loans and taxpayer money to pay for the projects.

"You have to dig up the street. You have to go right through people's neighborhoods," Lunn said. It's a daunting task.

But it's paid off: the city used to discharge anywhere from 6 billion to 12 billion gallons into the Grand River before the upgrades. That number decreased to 49 million gallons in 2011.

On the western shore of Lake Michigan, Milwaukee has a combined sewer system and has historically had overflow problems similar to Detroit. Since the mid-90s, however, discharges into Lake Michigan have dropped by 80 percent – largely due to a 405 million gallon underground tunnel to capture overflow, according to the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District.

The city added another 100 million gallons of underground storage capacity with two tunnels completed in 2006 and 2010, respectively. The price tag over two decades? $4 billion.

Heavy storms still tax Milwaukee's combined system – the city sent 2.8 billion gallons of untreated sewage and stormwater into Lake Michigan in 2010. Milwaukee has set a goal to completely eliminate discharges by 2035 and is turning to green projects – such as trees, rain barrels, porous pavement, planted rooftops – to bolster the recent tunnel additions.

Atlanta also spent $4 billion over the past decade separating its sewer and stormwater systems, improvements forced on the city by the federal government. "We had to inspect every linear foot of our system – 1,600 miles," said Jo Ann Macrina, commissioner of DeKalb County's Department of Watershed Management.

But Detroit has set aside only $57 million for system improvements this year. And the department is not looking at climate change projections as it plans upgrades, Schechter said.

"Population, population density, and economic growth/contraction are a more immediate concern," he said in an email.

Ken Kunkel, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist and North Carolina State University professor thinks that's a mistake – one not unique to Detroit. Few U.S. water and sewer utilities have reached out to NOAA about using climate data in planning sewer upgrades. Most rely on historic data.

"All models point to bigger storm events in the Midwest," Kunkel said. Utilities, he added, "should worry about it and be planning for it."

And some have. The Water Utility Climate Alliance formed in 2007 as a way for water and sewage service providers to incorporate climate data into future infrastructure plans. There are 10 utility members now. None are from the Midwest.

However, Milwaukee's recent long-term sewage district plan – aimed to completely eliminate discharges by 2035 – incorporated climate modeling, which prompted the heavy investment in porous concrete, as well as ponds, lakes and more natural areas instead of tunnels and more basins.

"Climate change has had an effect on recent precipitation patterns, and precipitation has a direct effect on the region's sewer systems," the city concluded in a recent report. "Green infrastructure is a safe 'no regrets" strategy."

A blueprint for Detroit's future

It's not all bad news: Detroit has seen some successes.

Combined sewer overflow discharges have reduced by more than 80 percent from the pre-1995 levels, according to the 2012 Alliance for the Great Lakes report. The city used to pour about 20 billion gallons of raw sewage into the Detroit River every year; now the average is about 2 billion, Schechter said.

Detroit started using the storage basins in 1998, bolstering capacity. Meanwhile, over the past 15 years, the wastewater treatment plant has expanded. But plans for a large storage tunnel in 2009 that would have further reduced overflows were scrapped because of lack of money.

Even though the nine holding basins have reduced overflow, Detroit needs "more innovative ways to deal with this than digging a big hole in the ground," said Brammeier, the Alliance's president.

Streams used to do a lot of the work – carrying excess water from storms to the Detroit River. But many have long since been rerouted underground into pipes. One intriguing idea to alleviate sewer stress is to "daylight" an old stream – Bloody Run Creek – by busting up the concrete and letting it flow freely again.

In March a coalition of city officials, business leaders and nonprofits released a blueprint for Detroit's future that recommended greening vast amounts of vacant space to alleviate sewer strain. The plan, dubbed Detroit Future City, calls for the creation of ponds, lakes, even forests to ease sewer pressure and soak up other forms of pollution.

It's cheaper to put in and maintain such natural areas compared to sewer system upgrades, the authors say. Detroit also happens to have a lot of vacant land – about 20 square miles, roughly the size of Manhattan.

There have been a couple of benefits to the vacancy, Schechter said. Overgrown lots capture water, and as industry has left, the department has far fewer problems with toxic metals in the incoming water.

The department has committed $50 million toward disconnecting unused downspouts, removing vacant houses, planting trees and installing trenches, among other "green" techniques aimed at reducing runoff into the Rouge River over the next two decades.

But it's hard to estimate how much runoff green space will capture, Schechter said. "If you build a basin to hold overflow, you know exactly what you're getting."

No one has put an exact price tag on the Detroit Future City plan. The suburban Detroit-based Kresge Foundation has pledged $150 million over the next 5 years to kick-start it.

Still, the city's ability to undertake any sort of ambitious renewal is very much in doubt.

A bankruptcy court now controls much of the city's financial fate; a state-appointed emergency manager is tasked with improving the city's bottom line and streamlining services. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department has been eviscerated, down to about 600 employees from twice that number a couple of decades ago, Schechter said.

But from the ashes, Knott, at the environmental justice nonprofit, and others see a chance at rebirth.

"This could be a crisis," Knott said. "It's also an opportunity to revitalize the city."