Canada’s melting ice roads leave First Nations stranded, sparking fights over mining and road funding

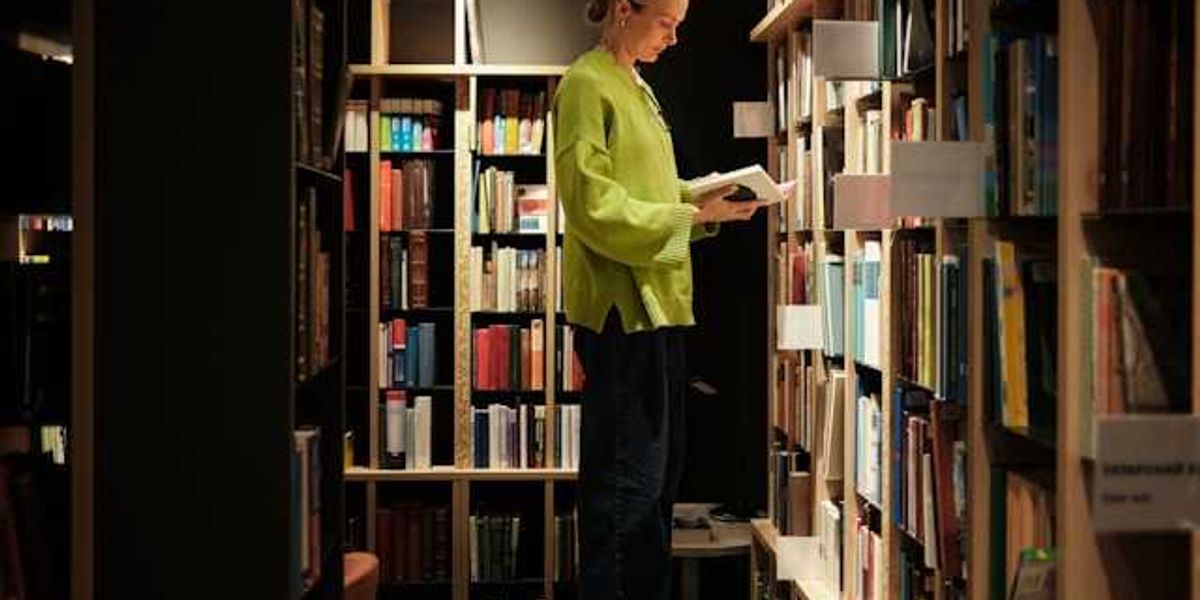

Winter roads that serve as essential supply routes for more than 50 remote First Nations communities in northern Canada are rapidly becoming unreliable as climate change thaws the frozen ground earlier each year.

Hilary Beaumont reports for Grist and Indiginews.

In short:

- More than 56,000 people across 50+ First Nations depend on winter ice roads, but warming temperatures have shortened the window for travel and transport, forcing expensive alternatives like air freight.

- As communities push for permanent all-season roads, government funding often comes with an implicit expectation of mining approvals, raising tensions over Indigenous sovereignty and environmental protections.

- Some First Nations, like Cat Lake, are trying to build permanent roads without backing mining projects, but face steep costs and limited support from provincial and federal authorities.

Key quote:

“We said no to the mine, and we said yes to the road.”

— Rachel Wesley, economic development officer, Cat Lake First Nation

Why this matters:

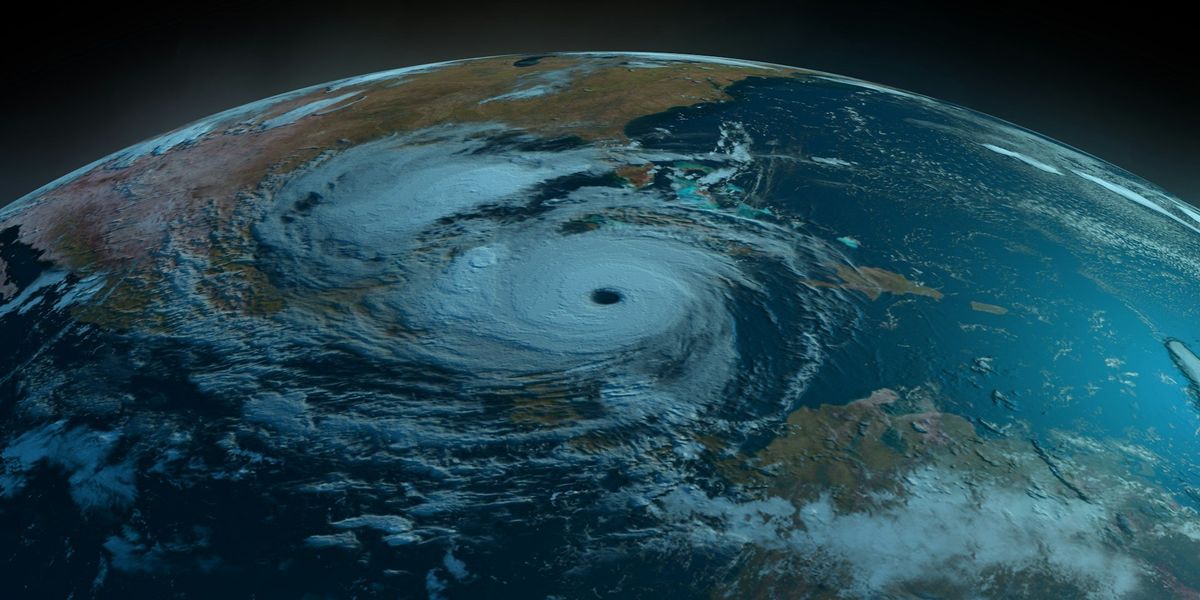

For remote First Nations, these seasonal roads are more than infrastructure — they are lifelines, enabling access to medicine, fuel, food, and connection to the outside world. Their disappearance means communities face higher living costs, deeper isolation, and harder choices. Many now face pressure to approve mining projects in exchange for permanent roads, risking their lands, water, and cultural survival. The minerals in these regions — vital to the green energy transition — lie beneath wetlands that store immense amounts of carbon. Mining them would release greenhouse gases on a scale comparable to the Amazon. As governments and corporations angle to tap this potential, Indigenous peoples must navigate coercive funding dynamics and colonial legacies.

Learn more: Unpredictable winters put northern Canada's vital ice roads at risk