Durable denial

Ten years after "ClimateGate," evidence be damned: Climate denial is alive and well.

Over the years, I've visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial dozens of times. It's hard to believe its striking design – a low, chevron-shaped wall of polished black granite containing the names of 58,000 Americans killed in the war – was once controversial.

The Wall captures the war's sadness, but with a note of sorry-ness thrown in. For decades, Vietnam vets, some now bedraggled and in their seventies, have stood guard at the Memorial for the tragically wrong notion that their MIA buddies are still alive in Hanoi prisons.

These guys, bless their hearts, always remind me that firmly-held beliefs often cannot be killed, even with the strongest contrary evidence or in the complete absence of confirming evidence.

Willfull misinterpretation

Climate deniers hold such beliefs. Ten years ago this month, they launched their best effort at a Pearl Harbor attack on climate scientists. They claimed a victory that, despite a decade-long torrent of contrary evidence, they still claim today.

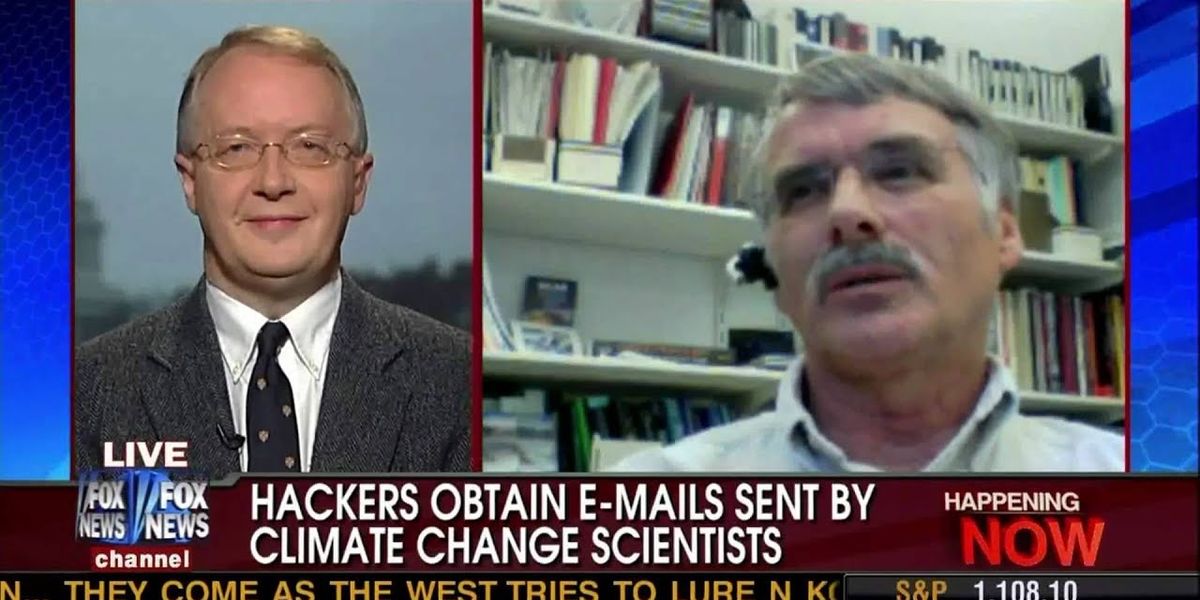

The theft of thousands of emails from the University of East Anglia's Climate Research Unit yielded a handful of messages between scientists that could be spun and willfully misinterpreted to suggest that the scientific near-consensus that climate science was a cynical and fraudulent scam.

In one particularly intemperate email, climate scientist Ben Santer muses about "beat(ing) the crap out of" Pat Michaels, a go-to scientist for climate deniers. Another appears to suggest that scientists conspired to use a "trick" to hide evidence that the earth was not warming.

The immediate impact of the emails was to run news coverage of the Copenhagen Climate Summit off the rails. The crucial world meeting started a few weeks after news of the email hack broke. Rather than unite around a message of urgency, climate scientists were on the defensive. ClimateGate played a role in Copenhagen's failure to reach a significant global agreement on climate action.

And deniers were suddenly working double shifts in the manufacture of doubt, their signature product. Suddenly, ClimateGate was "the worst scientific scandal of all time," with prominent climate scientists cast as corrupt and conspiratorial.

Multiple investigations cleared the scientists of anything worse than a few poor choices of words in a few purloined emails. But multiple layers of exoneration hasn't stopped the Denial-o-Sphere from waving the bloody flag years later.

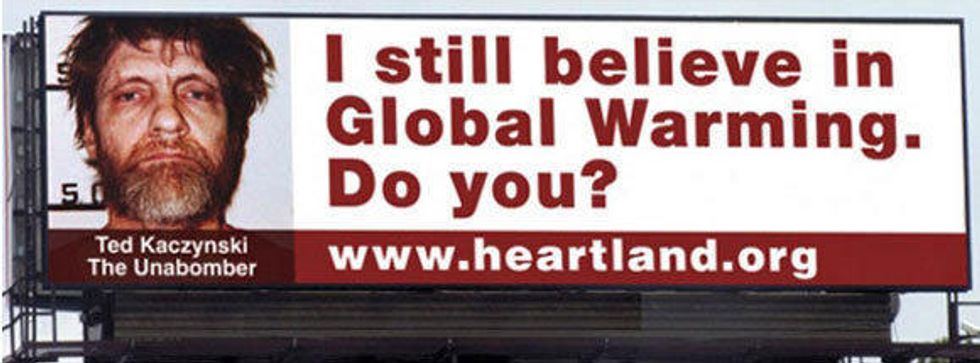

Police determined that the email hack was indeed a crime, but closed the investigation in 2012 without identifying suspects. Deniers have been repeatedly shamed in the past decade, notably by news reports that Exxon has ignored its own scientists on climate peril for decades; activists' sleuthing that some scientists, like Harvard's Willie Soon, were skewing their research to please fossil fuel funders; and of course the self-inflicted shaming of the Heartland Institute, who planned a series of billboards comparing climate action advocates to terrorists.

But like that hardy perennial horror flick character that springs back to life after you thought it was dead, climate denial is hard to kill.

The good news is that the hardest-core climate deniers appear to be walled off from reality, deeply embedded in a fact-free belief system. They no longer draw substantial attention from major media, with the predictable exceptions of Fox News, talk radio, and a few others.

The bad news is that, bolstered by ClimateGate and other myths, denial is alive and well in the White House, the Senate leadership, and virtually every key cabinet department. It's also enjoying a rebirth in key national governments like Brazil's.

That doesn't stop me from hoping, every day, that they're somehow right and the world's scientists and governments are embarrassingly wrong. I'd gladly be remembered as the world's biggest jackass if it meant that we're spared the climate miseries that surely await us.

It would be a whole lot cheaper and safer that way, assuming we don't stay hopelessly addicted to fossil fuels. If there were the slightest chance of the stubborn adherents to climate denial being right, I'd be happy to see every climate scientist and advocate, and every journalist who takes them seriously, look bad. It's a small price to pay for still having Miami.

But like that hardy perennial horror flick character that springs back to life after you thought it was dead, climate denial is hard to kill.

The good news is that the hardest-core climate deniers appear to be walled off from reality, deeply embedded in a fact-free belief system. They no longer draw substantial attention from major media, with the predictable exceptions of Fox News, talk radio, and a few others.

The bad news is that, bolstered by ClimateGate and other myths, denial is alive and well in the White House, the Senate leadership, and virtually every key cabinet department. It's also enjoying a rebirth in key national governments like Brazil's.

That doesn't stop me from hoping, every day, that they're somehow right and the world's scientists and governments are embarrassingly wrong. I'd gladly be remembered as the world's biggest jackass if it meant that we're spared the climate miseries that surely await us.

It would be a whole lot cheaper and safer that way, assuming we don't stay hopelessly addicted to fossil fuels. If there were the slightest chance of the stubborn adherents to climate denial being right, I'd be happy to see every climate scientist and advocate, and every journalist who takes them seriously, look bad. It's a small price to pay for still having Miami.