agriculture_industrial

Hog waste-to-gas: Renewable energy or more hot air?

Biogas could clean up manure and mitigate methane; but economics and inconsistent regulations remain hurdles

DURHAM, NC—On a school night in early spring, a rowdy collection of environmental activists, local residents, and Duke University faculty and students packed a public forum, railing against the school's plan to build a new $55-million gas plant on campus.

For nearly three hours, speaker after speaker denounced fossil fuels, decried fracking, and inveighed against the state's investor-owned utility. They begged the university to invest in a "sustainable future," one filled with wind and solar power, not natural gas.

But Tim Profeta, the chair of Duke's sustainability committee and the host of the meeting, had another idea. "We have an opportunity to become a demander of biogas, and not the fracked gas we've been hearing about all night," he said.

Since 2007, Profeta said, the university had been researching the capture of methane from hog manure to create electricity. The technology, called anaerobic digestion, could reduce pollution from the state's 10 billion gallons of swine waste – now stored primarily in open-air pits – and help meet a campus-wide goal of zero net greenhouse gas emissions.

Many in the crowd that night were skeptical. Was it really feasible?

A select group of faculty, staff and students thought it was. Two weeks after the forum, the panel made its recommendation to their university's top brass: only build the new plant if, within five years, Duke could purchase enough swine biogas to fuel it.

Campus leaders – who had been working toward a vote to approve the plant during a May board of trustees meeting – temporarily shelved their proposal.

The subcommittee's proposition was, in some ways, an elegant one. Long concerned about the pollution created by the state's 9.2 million hogs, the university helped pioneer a first-of-its-kind swine-waste-to-energy project in Yadkin County, North Carolina, in 2011.

By committing to make a major purchase of swine biogas, Duke believes it could spur the creation of nearly 300 similar-sized projects – more than doubling the number of anaerobic digesters on livestock farms nationwide, and creating useful lessons for a fledgling U.S. biogas industry.

The influx of projects would curb emissions of methane – the potent greenhouse gas many times more powerful than carbon – and cut odor and pathogens emanating from some of the state's 2,100 large-scale hog operations. It would create hundreds of short-term construction jobs and some long-term ones in rural areas of the state that sorely need them.

But critics see a messy side. They worry the benefits of methane capture are too limited, and could preclude more comprehensive cleanup of an industry that has anguished some neighbors and polluted waterways for decades. And though many climate analysts believe biogas can play a small but important role in displacing fossil fuels and reducing greenhouse gases, they say that doesn't justify the university's investment in expensive new gas infrastructure.

"Biogas is a perfectly laudable goal, and as a leading university in the country in a state that produces this much pork, it would be a very fine thing to incentivize and get going," says John Steelman of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who also happens to be a Duke graduate. "But don't link that to building a new gas plant."

For the moment, the university staff is trying to figure out how to make the swine gas recommendation a reality. Their success or failure could reverberate throughout the nation's biogas market and across other North Carolina campuses with commitments to reduce their climate footprint.

Biogas: A two-pronged attack on climate change

By curbing both carbon dioxide and methane, biogas plays a dual role in the steep greenhouse gas reductions that scientists believe are necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change.

To ratchet down carbon dioxide pollution, analysts say society must use less energy overall, and transition the entire economy to rely on clean electricity rather than burning coal, oil and natural gas.

Most researchers agree wind, solar and other non-combustion sources could get the country to almost 100 percent clean energy. But with today's technology, "nobody knows how we're going to get the last 5 or 10 percent," says Rob Sargent with Environment America.

That's because processes that require extremely high heat – like the production of plastics needed for medical devices – still rely on combustion. Jet planes and long-haul trucks still demand a liquid fuel source to travel great distances.

Thus, though he's generally circumspect on biogas, Sargent acknowledges, "there are some applications where it makes sense in the transition to straight-up renewables and storage."

Others say biogas could prove vital over the long term in decarbonizing society's hard-to-electrify elements – from heavy-duty vehicles to the gas stoves consumers may be loath to give up.

"The value of biogas … is really is an alternative for direct gas use for non- buildings, non-electric generation areas," says Amanda Levin of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who recently authored a strategy for cutting U.S. greenhouse gases 80 percent by 2050.

Most analysts believe biogas will play a small part in displacing fossil fuels. Levin's study, for example, found it would make up just 4 percent of all gas use by mid-century.

But biogas would play a vital role in curbing methane. Believed to be 36 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas, methane is far more prevalent in the atmosphere than previously thought, according to groundbreaking research published last year.

In 2015, the most recent year analyzed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, methane accounted for 10 percent of the country's greenhouse gas emissions. Natural gas drilling is a significant source of methane, but the agency's data show agriculture – through a combination of cattle digestion and livestock manure – is still the single largest source of the pollutant.

Thus, even if biogas plays a minute role in reducing carbon dioxide pollution, most researchers say there's ample benefit in displacing methane leaks from natural gas, and averting methane pollution wherever possible. Case in point: if the Durham plant could spur the creation of 289 more digesters the size of the Yadkin County one, the methane captured would cut as much greenhouse gas pollution as removing more than 175,000 cars from the road.

"Capturing the energy is better than not capturing the energy," Sargent says.

An investment that risks increasing fossil gas dependence

Despite the value of biogas in curbing global warming pollution, many advocates believe new infrastructure shouldn't be built to burn it – especially if used to create heat and electricity, two purposes that could be served by non-combustion renewable sources.

Fueling existing combined heat and power plants with biogas rather than natural gas – as the University of California system is considering – makes sense, they say. But a new power plant that would divert resources away from other clean energy investments does not.

"Duke is culturally resistant to making the kind of investments that will fundamentally change their energy system to something that is either all-electric, or gets away from steam as a general heating tool," Steelman says. "You're baking this added capacity into your long-term resource plan in lieu of more aggressive investments in efficiency and renewables."

Finally, there's concern that the plant could be built on a promise of biogas that never materializes – a particular worry since the proposal reflects a nationwide push by utilities to build combined heat and power plants on college campuses.

The ‘devil’s in the details’

Undoubtedly, the U.S. biogas market needs a kickstart. According to the American Biogas Council, of all the wastewater treatment plants, landfills, and livestock operations around the country that could economically capture methane, only about 14 percent do so at the moment.

By sheer number of facilities, the agricultural sector represents the country's greatest room for growth – with 8,700 swine and hog farms large enough to economically produce biogas, but just 265 on-farm digesters operating today.

Dairy farms make up the bulk of these, most in the Midwest, where farmers have sought to allay neighbor complaints about the smell of manure spread on fields. Dry cow manure is easily collected from already-confined animals and funneled to an above-ground tank, and its energy output is high.

Hog waste, however, has a high liquid content and produces less gas than dry cow manure. It's typically stored in open-air pits and costlier to move to a separate tank. And though the anaerobic digestion process can take place in a covered pit, or "lagoon," it relies on warm temperatures.

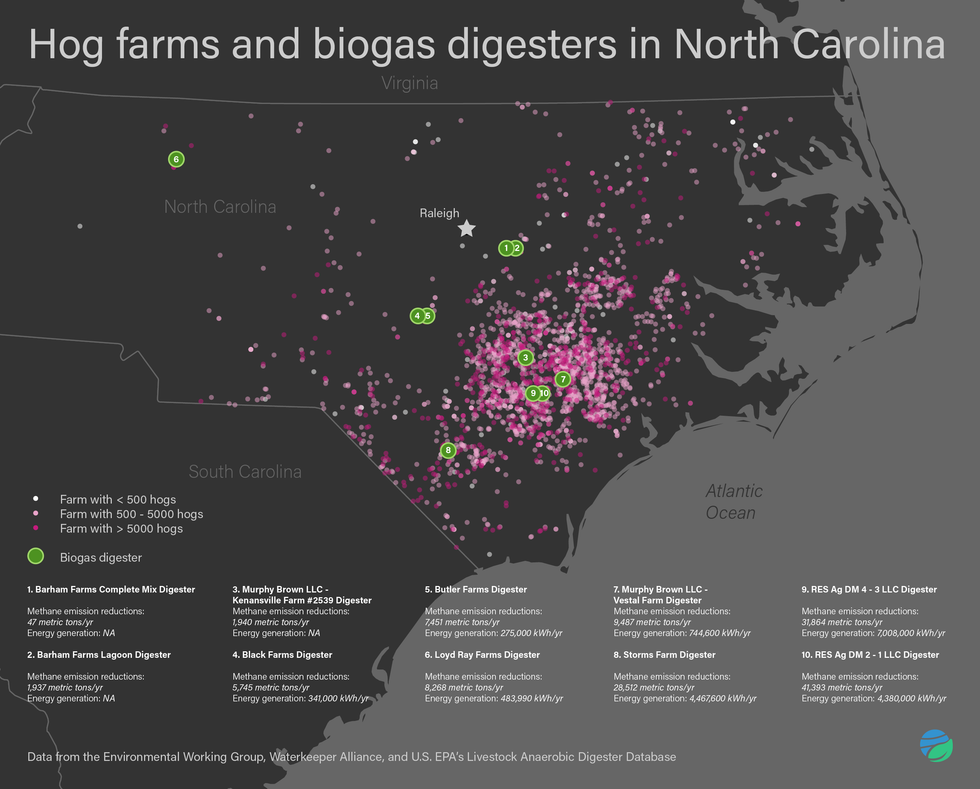

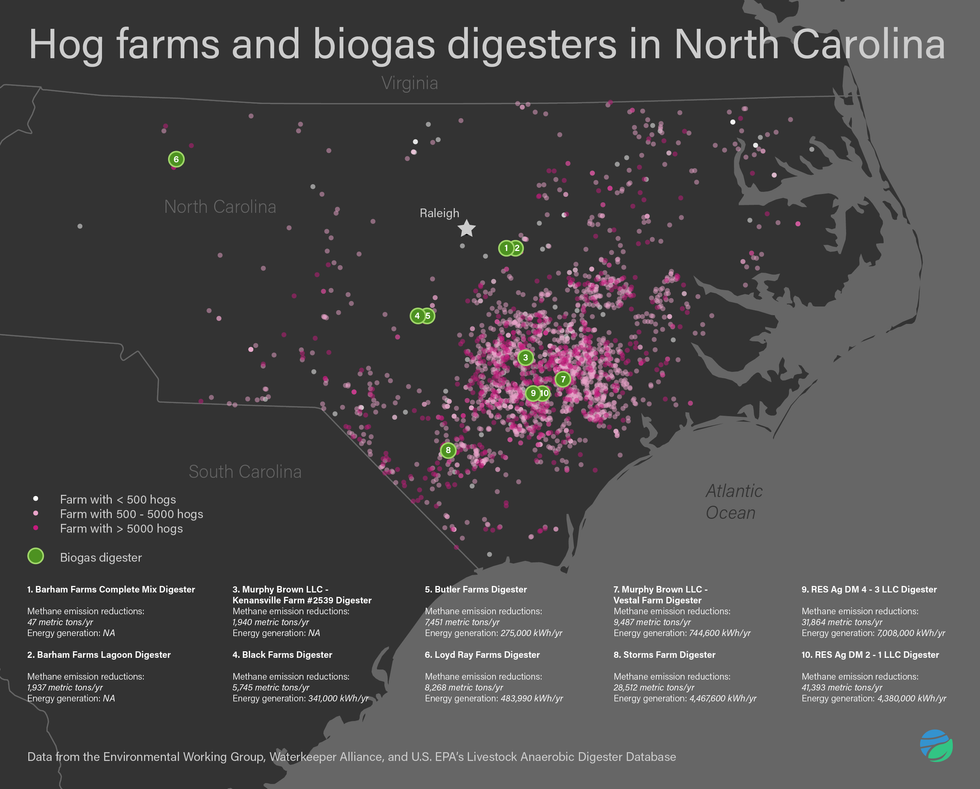

Those factors help explain why Iowa, which raises more hogs than any other state, has only two swine-waste-to-energy projects – and why Minnesota, which ranks third behind North Carolina in hog production, has none. And they point to how North Carolina – with its warm climate and hefty hog population – has become a pioneer in swine biogas, with 10 digesters now in operation and more soon to come online.

Still, with the third most biogas resources in the country, North Carolina lags far behind its potential – and its progress toward swine gas has come in fits and starts.

Some of the reasons are unique to the state: hurricanes and the spread of disease wiped out hog populations, reducing waste and the fuel they could produce. Also, out-of-state developers with expertise in energy but not hogs signed deals that fell through.

"They look at a map and they see all the swine farms and they see dollar signs," says Angie Maier with the North Carolina Pork Council. "But as with anything, the devil's in the details. It's very difficult to pull one of these projects off."

But other hurdles are common for biogas projects across the U.S. Like all emerging renewable energy sources, swine gas is more expensive than traditional fuels – which enjoy direct subsidies and no obligation to pay for the impacts of their pollution. In North Carolina, Duke Energy estimates biogas is roughly three times the cost of natural gas.

"Biogas systems are no different from any other renewable energy system in that they have to be conceived in a way that makes money," said Patrick Serfass, head of the American Biogas Council. "That's a challenge right now for the industry."

Policies designed to help level the economic playing field for biogas have been erratic over the last decade.

After Republicans swept the North Carolina legislature in 2010, they launched regular campaigns to repeal the state's 2007 clean energy mandate – which included a small but crucial swine-waste-to-energy requirement. A bipartisan majority always thwarted these attempts, but the signal to would-be biogas entrepreneurs was chilling.

"The industry needs the regulatory environment to be consistent," says Brian Barlia of Revolution Energy Solutions (RES), the project manager for one of the state's largest biogas projects to date, in Duplin County.

Removing a pillar that allowed an RES development in Magnolia, North Carolina, to turn a profit, in 2015 lawmakers also ended the state's 35 percent tax credit for renewable energy investment – one of the most generous in the nation.

Similarly, the U.S. Congress let a 30 percent investment tax credit for biogas projects expire in 2016. After that, Barlia says, "your two main economic drivers have been put to pasture." Without them, he says the Magnolia project – which came online in 2013 – would not have penciled out.

Selling electricity to regulated utilities also poses challenges. Though a 1978 federal law requires utilities to purchase power from small renewable energy developers, negotiating contracts and connections to the electric grid is no easy task for most farmers.

"We don't have a lawyer on staff," says Deborah Ballance, who, with her husband, runs Legacy Farms in North Carolina's Wayne County, where a digester system will be up and running in six months. "We had to go out and find someone who was knowledgeable about this. It's not every day you deal with a power company."

Ballance is one of the few who overcame other obstacles facing farmers considering building and running a digester themselves: lack of capital to invest in a system that can run $1 million or more, and the knowledge or inclination to apply for government grants that could assist them.

Even hosting an outside energy developer like RES is a significant decision for a farmer. "No matter how good the deal may look," says Gus Simmons, the state's leading biogas engineer, "there's no way that doing any of these projects doesn't change the farmer's world."

‘Heads begin to nod’ on biogas

But biogas proponents in North Carolina see signs of hope. Some of the Legislature's most rabid clean energy opponents have retired, while others are softening their views.

Duplin County's Rep. Jimmy Dixon, a "semi-retired" hog and turkey farmer, has co-sponsored bills to repeal or freeze the renewable energy law every legislative session since he joined the North Carolina House in 2010.

Now he says, "repeal is a bygone proposition at this point. We've invested too much time, energy, and human capital. People have complied with the law and they shouldn't have the rug pulled out from under them."

A sweeping, bipartisan clean energy law adopted this summer also may indicate a new era of magnanimity toward renewable fuels – and it includes a section prodding the utility to perform "expedited review" of swine waste-to-energy projects seeking interconnection.

Quicker reviews and connections, says Duke Energy's Travis Payne, "that's going to be a priority going forward."

Growing numbers of companies and campuses are joining Duke University in pledging 100 percent clean energy and "carbon neutrality," sustaining a voluntary market in which biogas producers can sell credits for curbing methane emissions. Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork-producer, has even committed to reducing its climate footprint by 25 percent.

According to the Pork Council, interested growers are meeting regularly with energy developers, the utilities, and university researchers to understand their options. Among farmers, there's more interest than ever before.

"Five, six years ago, if I was talking to groups of farmers [about biogas], I didn't have their full attention," Maier says. "Now, I see their heads nodding."

‘Most people looking at renewable natural gas’

One of the greatest sources of optimism for biogas proponents is the trend toward "renewable natural gas": removing impurities from methane and injecting molecules directly into existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure, as opposed to generating electricity onsite.

Sometimes called "directed biogas," the approach is already being used with swine waste-to-energy projects in Indiana, Missouri and Oklahoma. It means farmers or biogas developers don't have to negotiate with the electric utility to connect to the grid. What's more, burning renewable natural gas in a high-efficiency power plant produces more energy than less efficient on-farm generators could.

That's part of why Duke Energy plans major renewable natural gas purchases from two projects within the next year. Both in Duplin County, one will become the largest anaerobic digester in the nation – drawing on poultry and food waste as well as hog manure. The other, designed by the same engineer who helmed the Yadkin County project for Duke University and Google, comes online this month.

"We're trying a lot of technologies to meet our swine goals," says Duke Energy's Payne. "But honestly we're putting a lot of eggs in the directed biogas bucket."

There is some debate over what standards biogas must meet before it can be injected into pipelines and renewable natural gas still carries some added costs – cleaning the gas isn't cheap, nor is the infrastructure needed to connect farms to existing pipelines. In 2013, however, a Duke University study found pipeline injection of biogas could lower the cost of swine biogas to as little as 5 cents a kilowatt hour.

Renewable natural gas also opens the door for additional incentives – particularly critical in the wake of expired tax incentives for swine waste to energy. If the biogas is ultimately converted to transportation fuel, it can qualify for credits under the nation's Renewable Fuel Standard.

"That credit has a value, and it's a game changer. You can sell your [unit of gas] for $43 as opposed to three [dollars]," says Serfass of the American Biogas Council. Thus, "most people are looking at renewable natural gas these days just because of the enormous revenue upside."

Yet Duke University believes biogas will never really take off in the state – or perhaps the country – without an additional catalyst: Such as a wealthy school willing to pay top dollar for nearly as much biogas as state law already requires.

Tanja Vujic, who works in the office of the executive vice president at Duke University, and helped get the Yadkin County project off the ground, emphasizes their procurement would be on top of the existing swine gas requirement.

"There's not been a demand signal like this before, and there's not been such a motivated buyer before," she says. "Those two things together could really accelerate things."‘The top of our list’

A one-time staff member of the Environmental Defense Fund, Vujic believes the university can play a vital role in not just jumpstarting the state's market for waste-to-energy, but in paving the way for new manure management practices that take less toll on the surrounding waterways and communities. But, she says, "it's not all going to happen in one fell swoop."

As of this publishing, the university has made no new proposals public on the plant, or its plans to procure biogas. But Vujic is confident the campus will make it happen. "That's what my job is," she says. (Indeed, in the months since the power plant controversy first blew up, her title has changed to "Director of Biogas Strategy.")

Vujic's goals go beyond the subcommittee's recommendation. Her aim is to procure enough biogas not just to fuel the new power plant, but to displace all of the university's existing natural gas use – an outcome that, if done in connection with ramping down energy use overall – might appease some of the plant's sharpest critics.

Vujic is also hopeful the university's procurement can create models that can be exported throughout rural America, as the agricultural industry stakes out its role in mitigating climate change.

But most of all, she says Duke University is trying to minimize its climate footprint and maximize its benefit to North Carolinians. When she and her colleagues survey all the options, "methane from hog farms always comes out at the top of our list."

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms. This story was done in partnership with NC Policy Watch.

Related: Hog waste-to-gas: Renewable energy or more hot air?

Tomorrow: Treatment, taste and trends

Using biogas to clear the air near hog farms

North Carolina tries to mine its swine and deal with a poop problem that keeps piling up

YADKIN COUNTY, NC—A blanket of gray hangs over the hills refracting the late July sun and sealing in a thick scent of gas and compost.

Gus Simmons is sporting gray Levi's, a navy golf shirt, and a salt and pepper buzz cut.

The engineer climbs on top of what looks like a giant, charcoal-colored sail laid flat on the ground, anchored with a crisscrossing network of pipes, and billowing nearly head-high. Like a kid in a bouncy castle, he bounds across the rubber, covering half the distance of a football field.

Beneath him are 2.1 million gallons of animal feces. Behind him is a row of nine oblong barns, their fans blowing the stench from the thousands of hogs packed inside. Behind to his left, a contraption the size of a large cupboard creates electricity.

Simmons is conducting a tour of Loyd Ray Farms – a nearly 9,000-head operation in the northwest corner of the state.

Called an anaerobic digester, the rubber-covered-pit-of-excrement is Simmons' proud creation. Microscopic beings in the oxygen-deprived crater seize on the hog manure, separating it into methane gas – burned to create power for more than half the farm – and liquids, which are piped to an adjacent pond.

Simmons dashes to the pond. He flips a switch, creating powerful rapids. This reintroduction of oxygen, called aeration, reduces ammonia and other pollutants in the liquids before they are sent to an earthen pit for storage and irrigation.

Raised on a farm that he says grew "a little bit of everything," from hogs to row crops, Simmons has made his life's pursuit the design and construction of biogas systems like this one – the first of its kind in the state. But his work has implications far beyond Yadkin County.

Because anaerobic digestion reduces pathogens, odor, and volume, it offers a critical upside for managers of all types of organic byproducts – from animal manure to food waste to sewage. Harnessing methane gas – which would otherwise leak into the atmosphere – curbs a global warming pollutant many times more potent than carbon dioxide. And converting the gas to energy displaces fossil fuels, creating a small but crucial sliver in the renewable energy pie scientists say is necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

But challenges remain. Renewable gas is more costly than traditional fuels. Transporting it from the rural areas where it is produced to the urban areas where it's often needed can be difficult. And many would-be producers of biogas – from wastewater treatment plant operators to hog farmers – still lack the expertise, the will, or the capital to adopt the technology.

If Simmons and his colleagues can overcome these hurdles in North Carolina, they can set an example for policy makers, renewable gas developers, and others nationwide.

"Let me chat about odor for a second. Those of you who've been on hog farms before, I hope you notice that it's different," he says to the tour group, of the smell coming from the hog houses. Simmons implores them to note the more pleasant scent of the aeration basin. "I'm an eastern North Carolina farm boy. We used to plow bottomland, and you would smell this organic, earthy smell," he says, wistfully.

"That's what it smells like to me."A reflection of the local area

The science of anaerobic digestion described by Simmons is one that has evolved over hundreds of years.

In the 17th century, a Belgian scientist discovered that decaying organic matter created a substance, "far more subtle or fine…than a vapour, mist, or distilled oiliness, although…many times thicker than air." From "chaos," Jan Baptista van Helmont coined the term "gas."

Nearly 200 years later, British scientists determined this gas was methane. In 1859, the first biogas plant was built at a leper asylum in India. By the end of the 19th century, small digesters were popping up in India and along the coast of southern China.

Today, the size and manner of digesters varies widely across the globe.

"One of the universal truths of biogas systems is that they reflect the local area," says Patrick Serfass, head of the American Biogas Council.

Simple household digesters are widespread in rural parts of the developing world, where there's no electricity, natural gas, or centralized sewage treatment. Some 40 million people use them in China.

Europe, by contrast, leads the world in commercial-scale biogas, with more than 17,000 systems. While the circumstance in each European nation varies somewhat, says Serfass, "if there are two common denominators, it's high electricity prices and no space for landfilling."

He quickly adds, "those are two we don't have here, which is why the U.S. market is so different."

America has long had a vast network of pipelines and transmission lines, cheap electricity, and ample room for dumps. As a result, biogas development has lagged. Just more than 2,000 systems are now in operation, according to the American Biogas Council, the majority at sewage treatment plants to reduce volume.

And although the council estimates at least 8,700 dairy and hog operations in the country are large enough to profitably produce biogas, only 265 – 12 percent of them swine – do so.

But the tide may be turning. New sources of renewable energy are needed to replace gas, coal and oil, and stave off climate change. Analysts now recognize methane emissions from farms as a significant source of global warming pollution. And there's growing concern about food waste, which is now the single largest component in the nation's landfills.

‘So many hogs, so much manure’

All of these elements are at work in North Carolina, home to 10 of the nation's 32 swine-only biogas systems, more than any other state. But in evidence of Serfass's "universal truth," the main factor driving renewable gas here is a local phenomenon.

"There are just so many hogs, and there's so much manure, and it has to be managed," he says.

Concentrated in the southeastern part of the state, North Carolina's 9 million hogs – the second most in the country after Iowa – are largely the property of a handful of corporations. In a system pioneered by Duplin County's own Wendell Murphy, these corporate integrators contract with growers, many of them former tobacco farmers, to raise the animals. The integrators supply the growers with feed and ship the pigs to slaughter.

The contract farmers are left to manage the pigs' waste – 10 times that produced by a human. Most follow the same template: A clutch of rectangular sheds with slatted floors house hundreds of animals. Manure drops beneath the slats to a pit beneath the sheds, from which it is flushed into one or more open, earthen pits. Periodically, the liquid from these pits is sprayed onto nearby fields to irrigate and fertilize low-value crops like hay, which can stand the onslaught of nutrients.

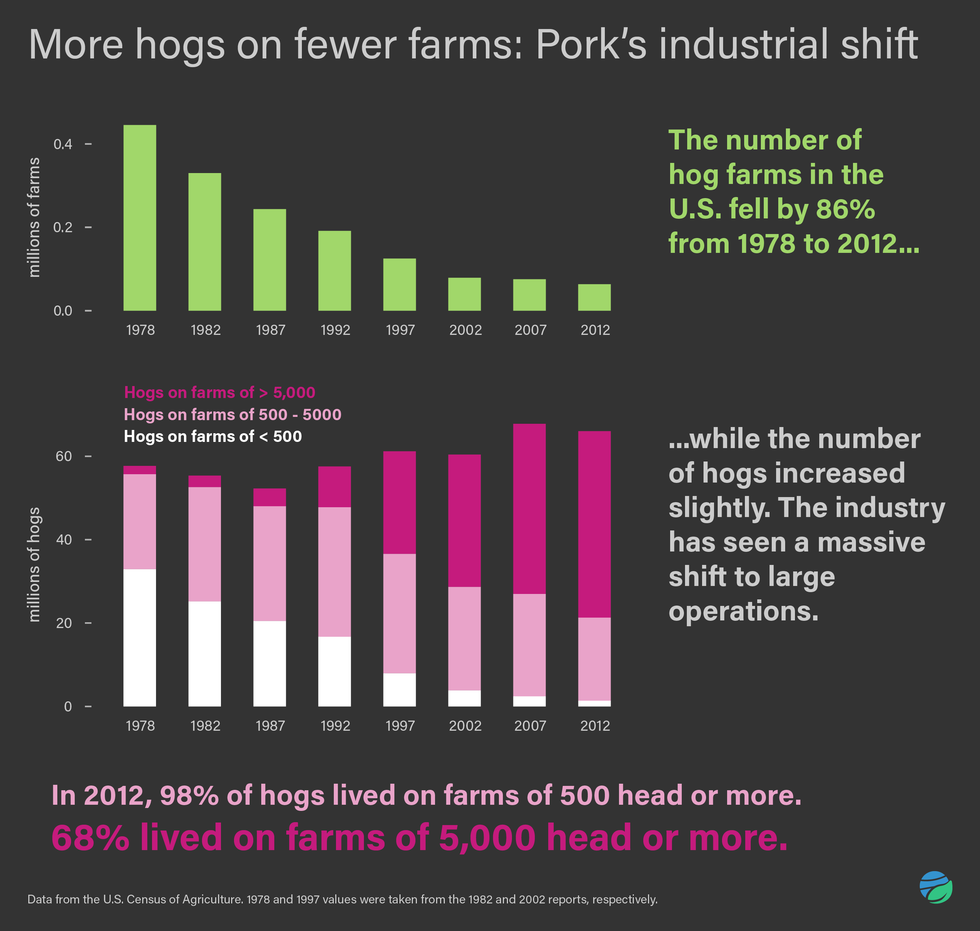

It's a strategy that may have worked well in 1980, before the state's hog population skyrocketed and thousands of hogs were concentrated on fewer and fewer farms, encroaching on streams and homes. But today, critics say, such handling of 10 billion gallons of swine manure each year poses grave problems for the environment and public health.

Heavy rains and hurricanes can cause open waste pits to burst and overflow. At least 14 did just that last fall when Hurricane Matthew dumped 15 inches of rain in the eastern part of the state.

Nutrients from spray fields are also appearing in nearby rivers and streams, producing algae blooms and in extreme cases, fish kills. One study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found swine operations causing water quality violations in 60 percent of nearby waterways.

At the same time, odors and pathogens from hog houses and sprayed liquids are tormenting and even sickening neighbors, according to the more than 500 eastern North Carolina residents who've filed a nuisance lawsuit against Murphy-Brown, LLC, the company Wendell Murphy built and sold to Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork producer.

Public awareness of these issues peaked in the 90's, forcing state leaders to attention. Before then, says Christine Lawson of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, "there were no regulations."

Among the most significant new rules of the decade, state lawmakers enacted a moratorium on new hog operations with more than 250 animals – unless they met tight standards for odor, pathogens, nitrogen, ammonia, and discharges into waterways. As part of an agreement with the Attorney General, Smithfield and Premium Standard Farms funded research into "economically feasible" measures, including methane capture, that might allow farmers to meet the new limits.

After more than a decade of wrangling, in 2007 the legislature passed two major laws that determined the industry's trajectory for another decade.

First, as part of a sweeping renewable energy measure, lawmakers created the nation's only requirement for electricity produced from swine gas. "I don't think anybody knew whether it would work or not," says longtime former legislator Joe Hackney, a Democrat who was then serving his first term as Speaker of the House. "It was well worth a try."

In a second law, the Legislature made permanent the ban on new or expanding industrial farms that didn't meet strict environmental standards, created a fund to help incentivize biogas production and other pollution control measures on existing farms that promised not to expand, and launched a pilot program on methane capture.

"It was a balance of the interests of the parties so that a bill could be passed," Hackney says. "The industry was trying to save itself."

The deal was bittersweet for activists who'd been fighting industrial-scale waste pits, or "lagoons," for years. "We were able to come up with a ban that says there will be no new lagoons in North Carolina," says Larry Baldwin, the longtime Lower Neuse Riverkeeper who now works with the national network Waterkeeper Alliance. "But the ones that are here are still here, and they're still creating havoc environmentally and in the communities."

Moving the ball along

Financed by Duke University and Duke Energy, and later by Google, Inc., the $1.2 million-dollar system at Loyd Ray was the first project to take advantage of both 2007 laws.

The utility counts the 600-megawatt hours of electricity generated – enough to power the biogas system and five of Loyd Ray's nine barns – toward its requirements under the renewable energy law. The university takes partial credit for the methane captured, the equivalent of removing 900 cars from the road, to offset some of its on-campus pollution and achieve its aim of zero net greenhouse gas emissions. Google claims the rest of the methane reductions to meet its own goal of 100 percent renewable energy.

A condition of receiving state incentives, the Loyd Ray system also goes beyond methane capture to meet the standards for odor and nutrient pollution, established in the moratorium law. The state funding also prevents the farm from expanding, but its owner and namesake, Loyd Bryant, has no plans to do. Instead, he's happy for the electricity generated, and the chance to do some good.

So is the surrounding community, says Tanja Vujic, who leads Duke University's efforts to research and procure biogas, and helped steer the Yadkin County project. "We had a ribbon cutting for the system after it was up and running. I had people come up to me who were neighbors." Unsolicited, Vujic says, they told her that they had been unhappy living near the farm – but now they could no longer smell it.

But some members of the July tour group weren't that impressed.

Elsie Herring, who lives next door to a hog operation in Duplin County, is one of the hundreds suing Murphy-Brown. She kept her nose covered for the bulk of the trip.

Lana Carter, who lives a mile and a half from a swine operation in Bladen County, also reacted to the stench. She was unconvinced the irrigation water was as clean as billed. "At the end of the day, they're still spraying it," she says.

Another concern: why was the waste-to-energy project so far west, on the only swine farm in the predominantly white county? Why weren't the mostly black communities in southeastern North Carolina getting any relief?

"It's going to be a while before they get to my neighborhood," says Carter, [who is African American.]

The other nine digester systems operating in the state are all to the east: one in Bladen County, one in Johnston, two in Harnett, the rest in Duplin. But none are meeting the strict environmental performance standards that Loyd Ray does – even with state incentive funds or the promise of expansion, no one could make the investment pencil out.

That's why Vujic and other backers of the Yadkin County project hope it can be fine-tuned, made more cost-effective, and implemented widely in the heart of hog country.

"Loyd Ray was just: 'we know we can do this, and we have to meet these standards, and this is our chance to move the ball along,'" Vujic says.

But some question the value of exporting the Loyd Ray model. Baldwin, of the Waterkeeper Alliance, believes biogas capture alone – without additional environmental safeguards – simply props up the old lagoon-and-sprayfield system. Plus, he worries the benchmarks met in Yadkin County may be too lenient.

"Even the Loyd Ray farm, it's better than what we have, but to me it's not enough," he says.

The standards may sound good, "but if they're not strong enough, what have we accomplished?" he adds.

In the coming months, Legacy Farms in Wayne County will put the standards to the ultimate test. Using a slightly different technology – in which dry bedding as well as hog manure is directed to a series of digesters and retaining ponds – the farm will become the second after Loyd Ray to meet additional limits on odor, nutrient, and pathogen pollution. They will exempt the farm of over 560 acres from the moratorium, allowing it to expand from 5,500 sows to 60,000 "finishing" animals.

Deborah Ballance, who runs the farm with her husband, is one of the state's few farmers completely independent from Smithfield or another integrator. The expansion allowed by the new system will allow the Ballances to raise animals until they are ready for slaughter.

"It wasn't working for us having to sell the weaned pig," she says. "It was better for us to maintain control throughout the whole process. This was a way for us to do that, and to keep our family farm."

She didn't say exactly how much the new system would cost, but did acknowledge it was in the millions. "I'm probably never going to retire," she says, chuckling.

Ballance lives on her farm, right next to the hog houses, as does her grown daughter and her family. She says they try hard to be good neighbors and have had no complaints. And, she noted, "we're right here – the first ones that are going to smell anything."

Putting together pieces of the puzzle

Despite the example of Legacy Farms, most observers don't believe there's demand for a dramatic increase in the total number of hogs raised in North Carolina, due to slaughtering capacity, available land for new and expanded farms, and other factors.

"I've not heard any serious conversation, anywhere, about expansion," says Andy Curliss, head of the North Carolina Pork Council. "Any type of biogas project, it's much more about dealing with what exists now."

"If there is any pent-up potential in North Carolina," says Kelly Zering, an agricultural economist at North Carolina State University, "it may be to relocate and concentrate existing pig production capacity."

The main appeal of biogas for the swine industry is the opportunity to turn a byproduct into an asset, Zering says in an email. Aside from that, "producers and integrators may find some non-monetary benefits, such as improved perception of them by neighbors and others in the state, as well as by investors and others outside North Carolina."

Some in the industry are already reaping these "non-monetary benefits" by hosting third-party renewable energy developers on their property.

Take Washington, D.C.-based Revolution Energy Systems (RES): The company operates two waste-to-energy systems in Duplin County in the tiny town of Magnolia, which has a population of about 1,200 people and is 40 percent Hispanic and almost one-third black.

Together the two new systems create 17 times as much electricity as the Loyd Ray project in Yadkin County.

The projects use the waste from more than 70,000 pigs, raised on ten adjacent operations under one owner, Murphy Family Ventures, a company started by Wendell Murphy's son.

Waste from the barns is scraped into a small holding tank that separates liquids and solids. Liquid is piped into a cylindrical, above-ground digester tank, two stories high and two rooms wide, painted a gleaming royal blue that lends an air of industrial efficiency.

Unlike Loyd Ray, there's no aeration pond for excess liquid; instead it's pumped directly into the lagoon that predated the digester. Even so, there's virtually no odor.

Gas is piped underground and stored in a white, futuristic-looking sphere. The contents are channeled to an electric generator; the waste heat is redirected back to the digesters to control the anaerobic process.

Like Loyd Bryant, Murphy Family Ventures incurred no cost for the biogas system, including retrofitting its barns with scrapers. Instead, the system is owned entirely by RES, and so are its benefits: renewable energy credits sold to Duke Energy to satisfy the 2007 law; methane credits equal to the pollution of nearly 7,500 cars sold on the offsets market; waste heat to aide digestion; revenue from electricity sold to the grid.

"From the host, to the utility, to the state, everything needs to be in harmony to make this happen," says Brian Barlia of RES.

‘Learning with every step’

A decade ago, when the swine biogas requirement became law, there was no sheet music for producing that harmony. Only a couple of swine farms around the country were capturing methane and creating electricity. There was no one right combination of scrapers, digesters, and onsite electricity generation, or guidelines for connecting to the electrical grid of a regulated utility.

"We were just scratching the surface of swine waste to energy," says Republican Rep. Jimmy Dixon, a "semi-retired" swine and turkey farmer from Duplin County, and one of the hog industry's staunchest defenders. "We were way, way, behind. We weren't on the starting line when the whistle was blown."

The result, says the Pork Council's Curliss, is that "everybody is trying everything."

Lawson, the engineer at the state's Department of Environmental Quality who has permitted all of the state's swine-waste-to-energy projects, has seen a range of schemes – from simple, covered lagoons, to multi-farm projects like RES's Magnolia. "There's experiential learning with every step," she says.

One Duplin County farm, called Vestal Farms, says Lawson, "has tried a menagerie of things," but none lasted. Now, that farm is part of a concept that's generating buzz in the biogas world.

Instead of burning gas onsite to create electricity – an added expense and operational burden – farmers can purify the molecules and inject them into the existing pipeline infrastructure. Customers can pay for a certain amount of "directed biogas" or "renewable natural gas" to be injected – in the same way some utilities allow customers to pay for a certain amount of renewable energy to be added to the electrical grid.

In November, an endeavor called Optima KV begins inputting biogas into a pipeline in Duplin County; Duke Energy will use it to help fuel its gas plants in Wayne and New Hanover counties.

It will become the largest biogas project in the state, large enough to power more than 800 homes, and the first to inject directly into a pipeline system. Five different farms, including Vestal, have invested in the system and will reap its benefits.

Unsurprisingly, it's the latest waste-to-energy innovation from Gus Simmons. And while Simmons is excited about the possibilities of renewable gas, he sees a future in which all the state's farms are, by one method or another, converting their waste into an asset.

"I think there's an opportunity for all of these farms to find a way," he says.

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms. This story was done in partnership with NC Policy Watch.

Related: Hog waste-to-gas: Renewable energy or more hot air?

Tomorrow: Bringing the "farm" back to hog farming

Cheap bacon and bigger barns turn Iowa inside out

Big Ag moves into rural communities and upends the social and economic balance.

CLEAR LAKE, Iowa—Chris Peterson has raised two children, thousands of hogs, a couple of rambunctious terriers and hell.

Lots of hell.

"The family farm is gone," he says tapping his kitchen table with gnarled workingman's hands, the fingernail on his index finger busted and purple. "And someone needs to know about it."

He shows me a local newspaper with an above-the-fold photo of him rallying a crowd against a proposed mega-hog farm. "Top story of the year," he says.

He speaks casually of driving presidential hopefuls around the state, offering reality. "We took John Kerry to a pile of dead hog stacked up on the side of the road, you know what he asked? 'Why are they all dying?' That's when he got it," Peterson says.

The "it"? A way of life that has industrialized over the past 30 years, undergoing a massive makeover. Hog raising has become faster, more efficient, more lucrative. Demand for pork is soaring worldwide: per capita consumption has shot up 7 pounds over the past 30 years.

To keep up, farmers raise hogs predominantly inside massive confinement barns and work for the handful of large corporations that dominate the market.

These changes have brought well-publicized pollution concerns. In Iowa, pig manure is so persuasive in waterways that the state has declared 750 of them impaired. And in North Carolina this year, researchers found pig poop bacteria on the homes of 14 out of 17 farm neighbors they tested.

But the most profound impact? Big Ag has upended rural communities, taking the fruits—meat and produce—from America's breadbasket and leaving a host of social, economic and environmental injustices behind: Plummeting home values, pressure that drives small farmers into tight contracts or out of business, shrinking populations and a diminished political voice in small rural towns.

For Peterson, preserving the rural farm life he loves now means regularly driving 40 miles in a night to attend a rally, butting heads with industry titans, visiting DC to buck the corporate farming trend. And dealing with the occasional death threat.

The 62-year farmer still raises a couple hundred black Berkshire hogs a year at his home off a dirt road here. He rocks back in his chair with Kirby, his terrier-greyhound mix, along his side. Peterson had the chair made four inches wider so Kirby could sit with him.

He shrugs off the death threats. "Somebody has to stand up," he says, tugging on his "America 1776" hat.

In every metric Iowa presents the poster child of hog farm consolidation and growth. Last year Iowa smashed a record—the state reached 22.4 million hogs, 7 percent higher than the year before and 30 percent higher than a decade ago, based on USDA data.

While the pork sales soar, an economic injustice plays out in Iowa communities.

Industry contraction means fewer farmers. That puts towns at an economic crossroads. The Iowa Economic Development Authority projects that due to consolidation, agriculture is the only major state industry that will lose jobs—approximately 1,850 over the next decade. Iowa, still overwhelmingly rural, had 6,321 new jobs in its 88 rural counties over the past five years, while the 11 metropolitan areas had 3 times that job growth, according to the Authority.

While small businesses in Iowa increased almost 30 percent over the past decade, the average number of non-farm small businesses per county declined about 25 percent in counties with large hog farms.

This runs counter to industry claims that consolidation and contract farming opens new markets and opportunities to farming communities.

"While ownership is much more concentrated, production is still spread out," says David Miller, director of research at the Iowa Farm Bureau. "Do you get rich doing it? No. But hog finishing is coming back as point of entry for people that want to farm for a living."

However, over the past four decades, the number of hog farms has plummeted by 90 percent. In 1977 the USDA counted more than a half million hog farm operations. Today the latest census reports 63,236. Our taste for cheap bacon and pork chops isn't the only force driving this contraction. As developing countries' economies grow, pork is one of the first indulgences of the newly empowered middle class.

Take China: Just four decades ago, meat was a rare luxury. As incomes grew, so did their taste for pork. In 20 years, from 1995 to 2015, China pork imports shot from nothing to more than 800 metric tons annually. Iowa sent more than $115 million worth of pork to China alone in 2016, a 23 percent jump from the year before.

Japan, Canada, Mexico and South Korea also love pork and represent the leading customers for Iowa, which, in 2016, exported about $1 billion of pork.

It's hard to see all that as I drive past classic Iowa scenery—corn, and some soybeans, as far as the eye can see. Interspersed are the long hog barns. But I don't see pigs.

In fact, you can drive for hours through farm country in the state that raises a third of the nation's hogs and not see a single one. But they're there—and there's no denying their impact on the state economy.

- The pork industry contributed $756 million in Iowa state taxes in 2015.

- The industry provides about 550,000 jobs nationwide; 141,813 jobs in Iowa alone.

- Nearly 1 in 12 Iowan's have a job tied to pork; the industry provides more than $8 billion annually in labor income.

- More broadly, about 6 percent of Iowa jobs come from livestock.

When a new barn with about 2,400 hogs goes up in Iowa, it generates roughly 14 jobs and $2.3 million in sales, part of which goes toward the approximately $1.56 billion in federal taxes the pork industry pays each year.

The industry's "doing more with less, and years ago it became apparent to a lot of farmers, you had to grow or get out," says Ron Birkenholz, communications director with the Iowa Pork Producers Association.

But there is backlash on the ground. People I visit—union organizers, retirees, farmers, truck stop cashiers, former teachers and a bunch of people that live at the end of the road for a reason—say these massive farms have eroded the communal aspect of rural life and push small-scale farmers out of business.

"All I ever wanted to do was farm," Peterson says. "Then all this shit came up."

“It’s an entirely different system”

Fresh off work at the local grain elevator, Nick Schutt sports a cut-off plaid shirt and dusty jeans. He greets me with a strong handshake, his oil-stained paw engulfing mine.

He shows me his father's 80 acres, where Schutt still farms corn and beans and occasionally tinkers with a tractor or two. Long-haired dachshunds bark, a rabbit skitters under a trailer and a barn cat hides. His uncle lives directly across the road.

"He and my dad drive out and meet every morning on the lawn mowers to talk … 'You hear what happened to so and so,' " Schutt tells me.

Schutt, 43, lives a couple minutes away and stops by to check on his parents and have supper after work most days.

Schutt wheels his mini-van down the rutted dirt roads of Williams. We're about an hour north—and a world away—from Des Moines off I-35. "These roads are rougher than a cob," Schutt says, blaming the animal confinement operations—mostly hogs, some cattle—within a few miles of his house, which bring truck traffic that the roads weren't designed to handle.

Almost two dozen confinement barns, representing thousands of animals, all sprung up within the past decade or so.

Much like Peterson, Schutt only wants to farm. It's in his blood. The irony of living in rural Iowa these days, he says, is that—counter to the Farm Bureau's assertion about easy entry points—farming is increasingly a rich man's game.

"We live in a state where agriculture is the No. 1 industry, and I can't make a living farming," he says. "I've been farming my whole life."

In 1950 Iowa had about 206,000 farms total. The most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture Census found that farm total had dipped to 88,637.

But hog totals persist. Iowa has almost seven hogs for every human in the state. The next highest state, North Carolina, has less than half that amount at 9.3 million hogs. The money dwarfs other states too—hogs are a $7.5 billion a year business in Iowa—comprising one-third of the national total.

"It's still one of quickest and easiest ways for young people to get into farming: You can get a few acres, put up a barn, become a pork producer," says Iowa Pork Producers' Birkenholz.

About 94 percent of hog farms in Iowa are family owned, according to Iowa Pork Producers. NC Farm Families, too, boasts that families run more than 80 percent of North Carolina's hog farms.

But many are what are referred to as contract farmers—raising hogs for large corporations. The farmers own the buildings; the hogs they're raising are owned by Iowa Select Farms and Christensen Farms.

"It's not just that we're better at [livestock raising] now," says Patty Lovera, assistant director of Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based group focusing on corporate and government accountability relating to food, water, and corporate overreach.

"It's an entirely different system."

The companies dictate how the farmer raises and cares for the hogs: how much space the pigs get, what they're fed, how their health is monitored.

Contract farmers raise approximately 44 percent of all hogs and pigs sold in the U.S. But there's a flip side to the economic impact: While Iowa now sells twice as many hogs compared to three decades ago, their value has plummeted.

Lovera and colleagues found that between 1982 and 2007 in Iowa, the market share of the top four hog processors almost doubled, the number of hogs sold in Iowa doubled, but the economic value of hog sales, adjusted for inflation declined by 12 percent.

Corporate giants can absorb plummeting values, Lovera says. Smaller, individual farmers cannot. Over that time Iowa lost 82 percent of its hog farms, and counties with the highest hog sales and biggest farms had worse and declining economies than state averages.

"We see the closure of local barns, fewer small town vets, things like that as well," says Adam Mason, state policy director with the nonprofit Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. "The infrastructure that supported family farms started to disappear."

Agricultural economist, author and sustainable farming advocate John Ikerd remembers times past. As a young man in southwest Missouri, he noticed that if farmers in the small towns got wealthy, there was a "bit of jealousy." But the less fortunate gained too, as a prosperous neighbor meant better silo infrastructure, a wider selection of threshing equipment, stronger banks. The whole community was buoyed.

"Farms of the past were more than just farms," says Diane Rosenberg, president and executive director of Jefferson County Farmers & Neighbors, Inc., in Iowa. "There were more people working the farms, there was the infrastructure like grain elevators, lockers, and processers. These CAFOs [confined animal feeding operations] come, and the money leaves the communities."

Birkenholz, of the Iowa Pork Producers Association, counters that hog operations are buffering communities from larger trends tearing at their economic fabric. "We know that there are some counties, communities that aren't doing too well," he says. "But in many of them farming is still the only thing keeping them above water."

When I speak with professor and researcher Frank Mitloehner of University of California, Davis on the phone, his answer to consolidation is cold and pragmatic: "The farm of the past—you know, the red barn-type scenario, pigs out in the wild—those days are long gone," he says.

The traditional hog farmer "raised hogs, repaired planters, fixed tractors, ground and made their own feed, they bought fuel and seed and fertilizer," says Ron Plain, an agricultural economist from the University of Missouri. "They had an enormous number of decisions and things to worry about.

"The fact is that large operations can do what they do more efficiently and at lower cost than small operations. I can hire someone and train them to do two things or three things, and it's much easier than having someone do 200 or 300 things," he says.

Efficiency is one part of it; another is corporate control over all aspects of pork—from piglet to market. Before large industrial farms there was a predictable pattern: hog prices go up to profitable levels, producers over-expand production. Then prices go down, producers lose money, cut production, and prices go back up.

Such cycles, and the inherent inconsistent profits, discouraged corporations from being too involved. They like stability and growth to keep investors happy.

However, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, hog slaughter and processing corporations started buying large concentrated feeding farms, making them both suppliers and buyers of the hogs, Ikerd says.

In doing this, they gained control of the market, driving hog prices down to $10 per hundredweight (100 pounds) in 1998, the lowest price in 30 years. Independent hog farmers simply couldn't stay in business at these bottomed-out prices. Big hog producing states—North Carolina, Iowa, Missouri—lost about 90 percent of their independent hog producers when large industrial farms showed up, many turning to contracts or simply finding another way to make a living.

Peterson was one of these farmers, handed a foreclosure notice on the farm in the late 90s.

"We lost $70,000 in net worth, and our collateral—hog equipment, feeders—all at once were worth nothing," he says. It got so bad that the local bank came after his children's things—clothes and other items they bought themselves.

Back in Williams, Iowa, where Schutt lives, the county, Hamilton County, is the eighth highest hog producer by sales in the U.S. The county's average farm size is 406 acres and livestock provides an estimated 10 percent of the jobs.

Schutt points out roadside ditches he mows for free to get hay for his hobby horses. He shows me his boarded up basement windows, where the smell from nearby confinements barns would settle and permeate the house.

We shake hands goodbye around 8 p.m. For him, it's time for dinner with mom and dad, a short drive down the dirt road home, and a bit of rest before another day of two jobs, mowing ditches, and, if he's lucky, a bit of time to wrench on a tractor.

Just steps from the giant red barn on his dad's land he speaks candidly about what will happen when his father passes. "My brothers and I will get some land, I'll probably get 20 acres," he says.

"I guess it'd be nice to have one job."

Property value plummets

When Gail and Jeff Schwartzkopf bought their home just outside Rudd, Iowa, it was a country dream.

Within three months, a hog confinement was put up about 2,000 feet from their new home. Now hanging outside means gagging or being mobbed by flies. They can't sleep with their windows open.

"We simply can't go outside," Gail tells Peterson and me as we chat at her kitchen table. The smell—when manure is applied during the day and winds change at night—in nearby fields is so powerful they've woken at 2 a.m., running around the house to close windows.

"I used to be so active working in my flower beds, enjoying the wildlife and the summer breezes … all that stopped when the CAFO went in," she says, adding that being forced indoors has made her gain weight, which is "too depressing to think about."

Floyd County, ranks 77th out of 99 Iowa counties for quality of life, according to rankings by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a public health-focused philanthropy organization. Gail, who works at a nearby Love's Travel Stop, has had co-workers tell her that the smell is part of living in the country. "They have no idea," she says.

Birkenholz echoes Gail's friends. "Hogs have always stunk, always will."

"Yes there's odor, but it's not continuous and not on a daily basis," he adds.

Gail begs to differ, and Birkenholz admits that the relationship with large farms and neighbors isn't always perfect.

The Pork Producers Association is working with farmers to address these concerns, working with Iowa State University and other groups to site new barns where they'll have the least impact on neighbors. Another effort focuses on vegetative buffers, he says. A line of trees around a barn, he says, "can really knock down some of that odor."

Such buffers can also capture up to 74 percent of dust from large confinement operations, according to a 2016 University of Iowa study.

Gail and Jeff show me the trees they planted around their property when they moved in. Jeff talks about growing up on a farm, working with his grandfather. When I ask them if they've thought of moving, Gail turns the question back to me: "Where would we go?"

"At our ages there aren't a lot of choices for employment in another state," she adds.

And while Gail doesn't ask it, there's also a question—a big question—of who'd buy her home: Big hog farms tend to destroy nearby home values. A 2008 Iowa study of more than 5,000 homes found houses within three miles downwind from a confined animal farm lost as much as 44 percent of their value.

Homes not directly downwind still suffered a 16 percent loss in value. And size matters: every 10 percent increase in size for the nearby farm correlated with a 0.67 percent decrease in home value.Breaking point

There's an undercurrent of rural rebellion in Iowa, and a lot of people are arming themselves with new knowledge about water, air, zoning and pork politics.

"I never thought I'd be an activist," Gail Schwarzkopf says, a refrain echoed from almost everyone I visit in Iowa.

Peterson and I leave the Schwartzkopf's and hop back on the highway. We climb in his Subaru and he ignores the car's seatbelt alarm.

His eyes are bothering him badly — "Damn diabetes," he says. He opens up to me about a troubled upbringing in Iowa, including a veteran father who returned to the U.S. only wanting to farm but who ultimately received a foreclosure notice—just as Peterson did in the late 90s.

Peterson's sore eyes tear up, but only briefly. He has a sick hog to deal with, an upcoming trip to DC, and more communities to rally.

Hell isn't going to raise itself.

Editor's note: This story is part of Peak Pig: The fight for the soul of rural America, EHN's investigation of what it means to be rural in an age of mega-farms.

Tomorrow: Pork, political sway and provoked communities

Jane Goodall: "Giving up hope won't save the planet. Ending poverty might."

We haven't inherited this planet from our parents; we've borrowed it from our children.

We are destroying the world at a very rapid rate, and an awful lot of people are just giving up hope and thinking, "Well, there's nothing I can do." The rain forests are disappearing everywhere. Big dams are draining whole countries of their water supply: The famous Serengeti, in Tanzania, is threatened by a dam in Kenya; and the Nile is being threatened by a huge dam in Ethiopia. There's mining, there's fracking, there's drilling for oil. We're in the middle of the sixth great species extinction; we're losing biodiversity in place after place. We're burning fossil fuels very, very fast.

We are breeding billions of animals to eat them, and that means that whole habitats are being destroyed to grow grain, masses of fossil fuel are being used to take the grain to the animals, the animals to slaughter, the meat to the table. In addition, the animals are producing masses of methane gas with their digestion, and that's a very virulent greenhouse gas.

Not only is the ice in the Arctic and Antarctic melting, but, very frighteningly, the permafrost is, too, releasing even more methane. This plus carbon dioxide, and a couple of other gasses, are blanketing the earth and trapping the heat of the sun. And that's led to climate change with terrible hurricanes and flooding and droughts.

There are certain things that must be done if we're to put the world right. One is alleviating poverty. Because if you're living in desperate poverty, you're going to continue destroying the environment in order to live.

People understand perfectly well that cutting down the last trees in a desperate effort to grow food is going to lead to terrible erosion. That erosion, in turn, will lead to the silting up of the water. Meanwhile, if you live in an urban area — including the U.S. — and you're very poor, then you buy the cheapest food. You can't afford to ask yourself how many miles did the food travel, did it harm the environment, did it result in animals suffering, did it involve child slave labor and so on.

But, we do need to start thinking how everybody else can lead more sustainable lives, particularly the very rich. There's just so much waste. That's partly because food isn't priced properly; there's no account made in the prices of cheap food for the cost that's very often involved in producing it.

The wealthy need to start thinking about their environmental footprint — what do I buy, what do I eat, what do I wear, how was it made, where did it come from — and thinking whether they need all the stuff that they buy and how they could live in more environmentally sustainable ways.

The urgent message is that, if we carry on with business as usual, then there's very little hope for sustaining human life on this planet in the manner to which people aspire today. The reason for all my lecturing is to, first of all, try and raise awareness about what's happening and, secondly, to try and help people understand there is something that can be done. So, for instance, by working with the MasterClass, I hope this message, and a whole lot more besides, can get out to a much, much wider audience.

One of the other programs that the Jane Goodall Institute supports is a humanitarian and environmental program for young people called Roots & Shoots. It started with 12 high school students in Tanzania, and now has members from kindergarten through university in 100 countries. The program's main message is that every individual makes a difference every day. Every group chooses itself three projects that are pertinent to the area around them that can make things better for people, for animals and for the environment — everything from planting trees to recycling to raising money for victims of earthquakes and hurricanes to growing organic food.

Of course, they also learn about what's going on in the world, how everything is interconnected and the urgency of trying to do something about it. And even if the young people in the program don't continue with the volunteer work, they certainly continue with an understanding of their life's impact.

I meet people all over Tanzania, and they say to me, "Well, it taught me that the environment is terribly important and I must try and preserve it. I'm getting my children involved Roots & Shoots in their school." In China, where we have about 2,000 groups, people tell me, "Well, of course, I care about the environment because I was in your Roots & Shoots program in primary school. Of course, I care about animals, I watched your documentaries about chimpanzees when I was in primary school."

I find that young people — when they know the problem, when you listen to them, when they're then empowered to take action — they just roll up their sleeves and get out there and go to work. And, as young people learn more, they are influencing their parents, they're influencing their grandparents — and some of them already are in high positions.

You very often hear that we haven't inherited this planet from our parents; we've borrowed it from our children. But, the way we're living today, we're stealing. We have been stealing for years, and we're still stealing their future today. In many places, we are using up more of the finite natural resources of the planet than nature can replenish. People have to start thinking. We have a window of opportunity for making some changes, for slowing down climate change. But it's going to require much more effort.

As told to THINK editor Megan Carpentier, edited and condensed for clarity.

China diverts 10 billion cubic meters of water to arid north in massive project.

Water supplies in north have been challenged by droughts, a surging population, agriculture, and manufacturing growth.

China diverts 10 billion cubic metres of water to arid north in massive project

by Reuters

Wednesday, 4 October 2017 02:19 GMT

Water supplies in north have been challenged by droughts, a surging population, agriculture, and manufacturing growth

BEIJING, Oct 4 (Reuters) - China has transferred 10 billion cubic meters of fresh water from the country's south to its drought-prone north in the few years since a massive water diversion project came onstream, authorities said on Tuesday.

In recent decades, water supplies in north have been challenged by protracted droughts, a surging population, agriculture, and unprecedented manufacturing growth.

China aims to ultimately supply 44.8 billion cubic meters annually to the north via the ambitious water diversion project. That would be about seven percent of the volume of water consumed by the entire country in 2015.

The expensive engineering project, which involves transferring water from the south via three major routes, was first mooted as early as the 1950s.

Along the middle route, the water pumped from the Yangtze River has gone to Beijing, Tianjin and the provinces of Henan and Hebei, according to the South-to-North Water Diversion Office under the State Council, or Cabinet.

The middle route carries water through canals, water highways and pipelines from Danjiangkou reservoir in central Hubei Province. It came into operation in late 2014.

The project has supplied 2.7 billion cubic meters of water to Beijing, serving 11 million people.

Currently about 70 percent of Beijing's water supply comes from the project. Previously the city's water supply came mainly from underground water.

Tianjin received 2.2 billion cubic meters of water while Henan and Hebei got 3.5 billion cubic meters and 1.1 billion cubic meters, respectively.

China aims to keep national annual water consumption below 670 billion cubic metres through to 2020, as part of efforts to ease chronic regional shortages by cutting waste and boosting efficiency.

(Reporting by Ryan Woo; Editing by Michael Perry)

Goodbye - and good riddance - to livestock farming.

The suffering inherent in mass meat production can't be justified. And as the artificial meat industry grows, the last argument for farming animals has now collapsed.

What will future generations, looking back on our age, see as its monstrosities? We think of slavery, the subjugation of women, judicial torture, the murder of heretics, imperial conquest and genocide, the first world war and the rise of fascism, and ask ourselves how people could have failed to see the horror of what they did. What madness of our times will revolt our descendants?

There are plenty to choose from. But one of them, I believe, will be the mass incarceration of animals, to enable us to eat their flesh or eggs or drink their milk. While we call ourselves animal lovers, and lavish kindness on our dogs and cats, we inflict brutal deprivations on billions of animals that are just as capable of suffering. The hypocrisy is so rank that future generations will marvel at how we could have failed to see it.

The shift will occur with the advent of cheap artificial meat. Technological change has often helped to catalyse ethical change. The $300m deal China signed last month to buy lab-grown meat marks the beginning of the end of livestock farming. But it won’t happen quickly: the great suffering is likely to continue for many years.

The answer, we are told by celebrity chefs and food writers, is to keep livestock outdoors: eat free-range beef or lamb, not battery pork. But all this does is to swap one disaster – mass cruelty – for another: mass destruction. Almost all forms of animal farming cause environmental damage, but none more so than keeping them outdoors. The reason is inefficiency. Grazing is not just slightly inefficient, it is stupendously wasteful. Roughly twice as much of the world’s surface is used for grazing as for growing crops, yet animals fed entirely on pasture produce just one gram out of the 81g of protein consumed per person per day.

A paper in Science of the Total Environment reports that “livestock production is the single largest driver of habitat loss”. Grazing livestock are a fully automated system for ecological destruction: you need only release them on to the land and they do the rest, browsing out tree seedlings, simplifying complex ecosystems. Their keepers augment this assault by slaughtering large predators.

In the UK, for example, sheep supply around 1% of our diet in terms of calories. Yet they occupy around 4m hectares of the uplands. This is more or less equivalent to all the land under crops in this country, and more than twice the area of the built environment (1.7m hectares). The rich mosaic of rainforest and other habitats that once covered our hills has been erased, the wildlife reduced to a handful of hardy species. The damage caused is out of all proportion to the meat produced.

Replacing the meat in our diets with soya spectacularly reduces the land area required per kilo of protein: by 70% in the case of chicken, 89% in the case of pork and 97% in the case of beef. One study suggests that if we were all to switch to a plant-based diet, 15m hectares of land in Britain currently used for farming could be returned to nature. Alternatively, this country could feed 200 million people. An end to animal farming would be the salvation of the world’s wildlife, our natural wonders and magnificent habitats.

Now it is time for a new revolution, almost as profound as those other great shifts: the switch to a plant-based diet.

Understandably, those who keep animals have pushed back against such facts, using an ingenious argument. Livestock grazing, they claim, can suck carbon out of the atmosphere and store it in the soil, reducing or even reversing global warming. In a TED talk watched by 4 million people, the rancher Allan Savory claims that his “holistic” grazing could absorb enough carbon to return the world’s atmosphere to pre-industrial levels. His inability, when I interviewed him, to substantiate his claims has done nothing to dent their popularity.

Similar statements have been made by Graham Harvey, the agricultural story editor of the BBC Radio 4 serial The Archers – he claims that the prairies in the US could absorb all the carbon “that’s gone into the atmosphere for the whole planet since we industrialised” – and amplified by the Campaign to Protect Rural England. Farmers’ organisations all over the world now noisily promote this view.

A report this week by the Food Climate Research Network, called Grazed and Confused, seeks to resolve the question: can keeping livestock outdoors cause a net reduction in greenhouse gases? The authors spent two years investigating the issue. They cite 300 sources. Their answer is unequivocal. No.

It is true, they find, that some grazing systems are better than others. Under some circumstances, plants growing on pastures will accumulate carbon under the ground, through the expansion of their root systems and the laying down of leaf litter. But the claims of people such as Savory and Harvey are “dangerously misleading”. The evidence supporting additional carbon storage through the special systems these livestock crusaders propose (variously described as “holistic”, “regenerative”, “mob”, or “adaptive” grazing) is weak and contradictory, and suggests that if there’s an effect at all, it is small.

The best that can be done is to remove between 20% and 60% of the greenhouse gas emissions grazing livestock produce. Even this might be an overestimate: a paper published this week in the journal Carbon Balance and Management suggests that the amount of methane (a potent greenhouse gas) farm animals produce has been understated. In either case, carbon storage in pastures cannot compensate for the animals’ own climate impacts, let alone those of industrial civilisation. I would like to see the TED team post a warning on Savory’s video, before even more people are misled.

As the final argument crumbles, we are left facing an uncomfortable fact: animal farming looks as incompatible with a sustained future for humans and other species as mining coal.

That vast expanse of pastureland, from which we obtain so little at such great environmental cost, would be better used for rewilding: the mass restoration of nature. Not only would this help to reverse the catastrophic decline in habitats and the diversity and abundance of wildlife, but the returning forests, wetlands and savannahs are likely to absorb far more carbon than even the most sophisticated forms of grazing.

The end of animal farming might be hard to swallow. But we are a resilient and adaptable species. We have undergone a series of astonishing changes: the adoption of sedentarism, of agriculture, of cities, of industry.

Now it is time for a new revolution, almost as profound as those other great shifts: the switch to a plant-based diet. The technology is – depending on how close an approximation to meat you demand (Quorn seems almost indistinguishable from chicken or mince to me) – either here or just around the corner. The ethical switch is happening already: even today, there are half a million vegans in the land of roast beef. It’s time to abandon the excuses, the fake facts and false comforts. It is time to see our moral choices as our descendants will.

• George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist

We’ve played chicken with food safety … and we’ve lost.

The meat industry is bad for us and bad for the planet. It’s time to end unsustainable 'food Fordism.'

We’ve played chicken with food safety … and we’ve lost

Felicity Lawrence

The meat industry is bad for us and bad for the planet. It’s time to end unsustainable ‘food Fordism’

Chicken being processed and labelled for sale to supermarkets in the UK.

Chicken being processed and labelled for sale to supermarkets in the UK. Photograph: For Guardian investigation with ITN

View more sharing options

Shares

170

Tuesday 3 October 2017 01.00 EDT

The dirty business of chicken processing is in the spotlight, with a Guardian undercover abattoir investigation revealing dodgy practices. As supermarkets suspend sales from the factory involved and Labour promises a parliamentary inquiry, some members of the food industry are sighing at the media’s obsession with the subject of poultry hygiene. But the subject will keep coming up, however much business wishes it away, because industrial chicken is one of the defining commodities of our era. Its cheapness comes at a high price.

The chicken scandal and a dysfunctional food industry

Letters: Readers respond to the Guardian’s exposé of the fiddling of food safety dates in the chicken supply industry

Read more

Meat production has quintupled in my lifetime, in large part thanks to the ubiquitous skinless factory chicken breast, and chicken accounts for around half of the meat we eat. At any one time there are more than twice as many chickens on Earth as humans – around 19 billion of them, bred to put on weight at turbocharged rates and mature in record time as uniform units of production that fit abattoir machinery. We have invented food Fordism – meat for the masses from the conveyor belt, no longer a luxury but an everyday ingredient. But, for all its apparent democratising possibilities, it is a commodity fraught with inescapable dilemmas.

Intensive livestock production is one of the most significant drivers of climate breakdown. It contributes nearly one fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions, rivalling the whole global transport sector. True, feedlot cattle leave a greater environmental footprint than poultry, but if you care about mitigating global warming, plant-based proteins are far better than intensively reared birds. Most of us in developed countries eat far more protein than we actually need for health, and most people could do more for the climate by cutting meat than giving up their car and plane journeys.

Politicians dare not say it for fear of sounding like Marie Antoinette, but the price of cheap is too high

As the world’s population grows, the question of how we produce enough to feed everyone becomes ever more urgent. Intensively reared livestock is an inefficient way of meeting needs. Farm an acre of decent land and you can produce 20kg (45lb) of animal protein from it; give the same acre over to producing wheat and you’ll get 63kg of protein. If the grain that is currently used to feed animals were fed directly to people, there might be just enough food to go round when population peaks. If instead we continue to spread our industrial meat habit to poorer countries, we’ll need three planets to feed the world. The ethical argument is overwhelming: we need to get back to thinking of meat as a luxury, to be enjoyed occasionally, if not entirely forsworn.

Advertisement