injury

Why it's so dangerous to walk through floodwaters

Disasters make 14 million people homeless each year.

About 14 million people are being made homeless on average each year as a result of sudden disasters such as floods and storms, new figures show.

Eight of the ten countries with the highest levels of displacement and housing loss are in South and Southeast Asia

By Adela Suliman

LONDON, Oct 12 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - About 14 million people are being made homeless on average each year as a result of sudden disasters such as floods and storms, new figures show.

The risk of displacement could rise as populations swell and the impacts of climate change become more severe, said a report issued on Friday by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) and the Geneva-based Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

Earthquakes, tsunamis, floods and tropical cyclones are the main disasters forecast to uproot large numbers of people, with countries in Asia, home to 60 percent of the world's population, hit particularly hard, according to modelling by the agencies.

Eight of the ten countries with the highest levels of displacement and housing loss are in South and Southeast Asia.

They include India, where an average of 2.3 million people are forced to leave their homes annually, and China with 1.3 million people uprooted each year, found the report, released on the International Day for Disaster Reduction.

The numbers exclude those evacuated ahead of a threat, and people displaced by drought or rising seas.

Russia and the United States also feature as countries where disasters could cause large-scale homelessness, unless significant progress is made on managing disaster risk, the study said.

"The findings underline the challenge we have to reduce the numbers of people affected by disasters," said Robert Glasser, the U.N. secretary-general's special representative for disaster risk reduction.

"Apart from death or severe injury in a disaster event, there is no more crushing blow than the loss of the family home," he added in a statement.

The most devastating floods to hit South Asia in a decade killed more than 1,400 people this year, and focused attention on poor planning for disasters, as authorities struggled to assist millions of destitute survivors.

Refugees and people uprooted in their own countries are already at record-high numbers, said IDMC director Alexandra Bilak. The new model goes some way towards predicting the risk of disaster-related displacement, which is an "urgent, global priority", she noted.

It is also intended to help urban planners in hazard-prone towns and cities who must consider the safety and durability of built-up areas and the threats to millions living there. Justin Ginnetti, head of data and analysis at the IDMC, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation there was a strong correlation between the risk of being uprooted by a disaster and residing in a rapidly urbanising location.

With the poor often living on the outskirts of cities, on flood plains or along river banks, Ginnetti said better urban planning could make them less vulnerable.

He contrasted Japan and the Philippines, which have roughly the same number of people exposed to cyclones. Japan builds more robust housing and so faces far less displacement in a disaster than the Philippines, where homes are less able to withstand shocks, he said.

"We don't want people to think of disaster displacement as some kind of inevitable act of God - this is not (a) necessary outcome every time there's heavy rainfall," he said.

'Katrina brain': The invisible long-term toll of megastorms.

Long after a big hurricane blows through, its effects hammer the mental-health system.

Bryan Tamowski for POLITICO

The Agenda

AGENDA 2020

'Katrina brain': The invisible long-term toll of megastorms

Long after a big hurricane blows through, its effects hammer the mental-health system.

By CHRISTINE VESTAL 10/12/2017 05:10 AM EDT

Facebook Twitter Google + Email Print

NEW ORLEANS — Brandi Wagner thought she had survived Hurricane Katrina. She hung tough while the storm’s 170-mph winds pummeled her home, and powered through two months of sleeping in a sweltering camper outside the city with her boyfriend’s mother. It was later, after the storm waters had receded and Wagner went back to New Orleans to rebuild her home and her life that she fell apart.

“I didn’t think it was the storm at first. I didn’t really know what was happening to me,” Wagner, now 48, recalls. “We could see the waterline on houses, and rooftop signs with ‘please help us,’ and that big X where dead bodies were found. I started sobbing and couldn’t stop. I was crying all the time, just really losing it.”

Twelve years later, Wagner is disabled and unable to work because of the depression and anxiety she developed in the wake of the 2005 storm. She’s also in treatment for an opioid addiction that developed after she started popping prescription painkillers and drinking heavily to blunt the day-to-day reality of recovering from Katrina.

More than 1,800 people died in Katrina from drowning and other immediate injuries. But public health officials say that, in the aftermath of an extreme weather event like a hurricane, the toll of long-term psychological injuries builds in the months and years that follow, outpacing more immediate injuries and swamping the health care system long after emergency workers go home and shelters shut down.

That’s the rough reality that will soon confront regions affected by this year’s string of destructive hurricanes. As flood waters recede from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria and Nate, and survivors work to rebuild communities in Texas, Florida and the Caribbean, mental health experts warn that the hidden psychological toll will mount over time, expressed in heightened rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, domestic violence, divorce, murder and suicide.

Brandi Wagner's home in Lafitte, La., left, and the nearby bayou, Bayou Barataria, right. Below, sandbags line the street across from Wagner's home as Hurricane Nate approached earlier this month. | Bryan Tamowski for POLITICO

Renée Funk, who manages hurricane response teams for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says it has become clear since Katrina that mental illness and substance abuse aren’t just secondary problems—they are the primary long-term effect of natural disasters.

“People have trouble coping with the new normal after a storm,” Funk said. “Many have lost everything, including their jobs. Some may have lost loved ones, and now they have to rebuild their lives. They’re faced with a lot of barriers, including mental illness itself,” she said.

In New Orleans, doctors are still treating the psychological devastation of Katrina. More than 7,000 patients receive care for mental and behavioral health conditions just from the Jefferson Parish Human Services Authority, a state-run mental health clinic in Marrero, just across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. At least 90 percent of the patients lived through Katrina and many still suffer from storm-related disorders, according to medical director and chief psychiatrist Thomas Hauth, who adds that he and most of his fellow clinicians also suffer from some level of long-term anxiety from the storm.

“Every year about this time, I start checking the National Weather Service at least three times a day,” he said.

These long-term mental health effects of extreme weather are a hidden public health epidemic, one that is expected to strain the U.S. health care system as the intensity and frequency of hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes and other natural disasters increase in coming decades because of global warming and other planetary shifts.

With climatologists promising more extreme weather across the country, mental and behavioral health systems need to start preparing and expanding dramatically or demand for treatment of the long-term psychological effects of future natural disasters will vastly outstrip the supply of practitioners, said Georges Benjamin, director of the American Public Health Association.

Dr. Thomas Hauth, a psychiatrist, in his office at the Jefferson Parish Human Services Authority in Marrero, La., where he treats residents still suffering from anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders caused or exacerbated by Hurricane Katrina. Hauth and his colleagues also report post-storm anxiety and other conditions. | Bryan Tamowski for POLITICO

“On a blue sky day, our mental health resources are stretched,” said Carol North, researcher and professor of psychiatry at University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas. “There’s a lot we don’t know yet, but common sense tells us that more disasters and worse disasters will lead to worse psychological effects.”

”Katrina brain”

For climate change believers, this year’s string of record-breaking Atlantic hurricanes was just a warm-up for what scientists predict will be more frequent extreme weather events in the future.

When an entire city experiences a significant trauma at the same time, as New Orleans did during Katrina and Houston did during Harvey, it can push a lot of people over the edge, said Eric Kramer, another doctor who worked in the Jefferson Parish clinic: “Some people can rely on their inner strength and resilience to get through it, but others can’t.”

In the aftermath of Katrina, many survivors struggled with short-term memory loss and cognitive impairment, a syndrome dubbed “Katrina brain,” according to a report by Ken Sakauye, a University of Tennessee professor of psychiatry who was at Louisiana State University at the time.

Even though more than half the population of New Orleans had evacuated, psychiatric helpline calls increased 61 percent in the months after Katrina, compared with the same period before the storm, death notices increased 25 percent, and the city’s murder rate rose 37 percent, Sakauye wrote.

A year after Katrina, psychiatrist James Barbee reported that many of his patients in New Orleans had deteriorated from post-Katrina anxiety to more serious cases of depression and anxiety. "People are just wearing down," Barbee said. "There was an initial spirit about bouncing back and recovering, but it's diminished over time, as weeks have become months.”

In a longitudinal study comparing the mental health of low-income single moms in New Orleans before and after Katrina, one in five participants reported elevated anxiety and depression that had not returned to pre-storm levels four years later, said Jean Rhodes, study co-author and professor of psychiatry at University of Massachusetts Boston.

Hurricane Katrina killed 1,800 people in 2005, and left behind massive property damage. But publiGetty Imagesc health officials are learning that the longest-lasting damage of several storms is psychological. | Getty Images

For a smaller percentage of people in the study, particularly people with no access to treatment, symptoms of anxiety developed into more serious, chronic conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, the researchers found.

These aren’t cheap conditions to treat. One study cited by the CDC estimated the cost of treating even the short-term effects of anxiety disorders at more than $42 billion annually; double-digit regional leaps in rates of anxiety could cause serious financial strain to patients, employers, insurers and the government.

Vicarious reactions

Some damage can take place outside the storm-hit region. Even for people who have never experienced the raging winds, floods and prolonged power outages of a hurricane, this season’s repeated images of people struggling against the storms on television and other news and social media created unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression nationwide, said Washington, D.C., psychiatrist and environmental activist Lise Van Susteren.

“There is a vicarious reaction. When we see people flooded out of their homes, pets lost, belongings rotting in the streets, and people scared out of their wits, we experience an empathic identification with the victims,” she said.

Brandi Wagner pulls out the medications she must take on a daily basis to control a range of storm-related disorders including anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and an addiction to opioids. | Bryan Tamowski for POLITICO

“People come in saying they can’t sleep, they’re drinking too much, they’re having trouble with their kids, their jobs or their marriages are falling apart. They may not know where the anxiety is coming from, but everyone is affected by the stress of climate change.”

The same kind of vicarious reactions were documented after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York and Washington and after Hurricane Katrina, particularly in children, said Columbia University pediatrician and disaster preparedness expert Irwin Redlener.

“The mental health effects of natural disasters are really important and vastly overlooked, not only acutely but over the long term,” he said.

Everyone who lives through a major storm experiences some level of anxiety and depression. But for low-income people and those without strong social supports, the symptoms are much worse, said Ronald Kessler, an epidemiologist and disaster policy expert at Harvard Medical School. The same is true for people who already suffered from mental illness or drug or alcohol addiction before the disaster occurred.

Repeated exposure to weather disasters is another risk factor for mental and behavioral disorders. Hurricane Katrina decimated New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005, followed by Hurricane Rita less than a month later. Three years after that, Hurricane Gustav hit the Louisiana coast, followed by Hurricane Ike two weeks later.

In September, many who had fled Hurricane Katrina and resettled in Houston had to relive the same horrors all over again, putting them at higher risk for long-term mental health problems.

TOP LEFT: Wagner in her backyard. TOP RIGHT: Wagner's medications. BOTTOM LEFT: Wagner shows off a photo of her son, Sgt. Aaron Briggs, receiving his sergeant badge in a photo on her phone. BOTTOM RIGHT: Wagner's daughter, Jessica Briggs, her grandson, Jeremy Goudeau Jr., and her daughter, Kristina Briggs, at her home in Lafitte, La.. | Bryan Tamowski for POLITICO

But perhaps the greatest risk of adverse mental health reactions to storms occurs when an entire community like New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward is so completely destroyed that people can’t return to normal for months or years, if ever. For those who left and went to live in Houston, Atlanta and other far-flung cities, the dislocation and loss of community was equally harmful, researchers say.

“People are only physically and mentally resilient to a point and then they are either irretrievably injured or they die,” Kessler said. If storms intensify in the future, the kind of devastation parts of New Orleans experienced could become more common, he said.

Psychiatric First Aid

In the past decade, first responders and public health workers began training in a type of mental health first aid that research has shown to be effective in lowering anxiety and reducing the risk that the traumas experienced during a storm will lead to serious mental illness.

Using evidence-based techniques, rescue workers reassure storm survivors that feelings of sadness, anger and fear are normal and that they are likely to go away quickly. But when survivors complain that they’ve been crying nonstop, haven’t slept for days or are having suicidal thoughts, rescue workers are trained to make sure they get more intensive mental health care immediately.

In Houston, for example, teams of doctors, nurses, mental health counselors and other health care professionals offered both physical and mental health services at clinics set up in every storm shelter. The city’s emergency medical director, Davie Persse, said the clinics were so successful that local hospital emergency departments reported no surges in patients with psychiatric distress or minor injuries.

Forced evacuation, whether temporary or permanent, can also trigger psychological problems for people confronted by natural disasters. | Wikimedia Commons

Another important factor in reducing the psychological impacts of a storm is avoiding secondary traumas like being stranded for weeks in the convention center in New Orleans, said Sarah Lowe, a co-author of the Katrina study who teaches psychology at Montclair University in New Jersey. “Repeated traumas can pile up almost the way concussions do.”

“What I’m seeing in Harvey and Irma is there’s more mitigation of secondary trauma,” Lowe said. People were allowed to take their pets to the shelters with them, for example. In Katrina, survivors either had to leave their pets behind or stay in their homes and be more exposed to physical and mental dangers.

Evacuation and relocation

Some public health experts say that we need to start thinking of longer-term solutions to the longer-term problem of severe weather; instead of trying to treat post-storm psychological damage, we should avoid it in the first place by persuading residents to move out of storm-prone areas.

“We do a great job with preparedness and response to hurricanes in this country. It’s an amazing accomplishment,” said Mark Keim, an Atlanta-based consultant who works with the CDC and the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Health. “But as climate change progresses over the next one hundred years, what are we going to do—respond, respond, respond? We can’t afford that anymore.”

According to Keim, much of the rest of the world is already taking that approach:

“Hurricanes can’t be prevented, but by refusing to rebuild in flood plains and developing the infrastructure needed to reduce inland flooding and coastal surges, we can avoid much of the human exposure to the coming storms. That’s where the world is right now in disaster management. Preparedness and response are older approaches.”

Climate change experts agree. To avoid increasing loss of lives from the mega storms expected in the decades ahead, large coastal populations should relocate, researchers say. Mathew Hauer, a demographer at the University of Georgia, recently found that a predicted 6-foot rise in sea levels by 2100 would put 13 million people in more than 300 U.S. coastal counties at risk of major flooding.

But relocating large populations has its own risks. For the hundreds of thousands of New Orleans residents who rebuilt their lives far from home after Katrina, the loss of social ties and the stress of adapting to new surroundings also took a heavy psychological toll, according to recent research at the University of California.

There’s another problem with relocating people from coastal regions. It’s not just hurricanes that are expected to plague the planet as the climate shifts. Wildfires, droughts, inland flooding, tornadoes, earthquakes and other natural disasters are also expected to increase in frequency and intensity, making it hard to find a safe place to put down new roots.

“Whether people decide to stay or decide to move, which means giving up a way of life, the long-term psychological costs of climate change appear to be inevitable,” Harvard’s Kessler said. “We can expect a growing number of people to have to face that dilemma. They’ll be affected by extreme weather one way or another, and they will need psychological help that already is in short supply.”

Christine Vestal is a reporter for Stateline, a nonprofit journalism project funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Mid-air turbulence set to triple due to climate change, scientists warn.

Commercial airliners will be buffeted by up to three times more turbulence in future decades, according to a new report.

Commercial airliners will be buffeted by up to three times more turbulence in future decades, according to a new report.

Experts have warned the risk of mid-air injuries will rise and passengers can expect to spend more time confined to their seats with the seatbelt sign switched on due to rougher skies disturbed by climate change.

On some popular routes for UK travellers, such as transatlantic flights, instances of severe turbulence will increase by 180 per cent, while over Europe the rate is set to worsen by 160 per cent.

Scientists had already noticed that so-called clear-air turbulence (CAT) was on the rise, however the new study by the University of Reading is the first to come up with a comprehensive mathematical model predicting long-term global conditions.

It estimates that by 2050 the rate of inflight injuries will have almost tripled in line with the increased volume of turbulence.

The research team called for better forecasting systems allowing cabin crew to get their passengers seated and belted in time.

“Air turbulence is increasing across the globe, in all seasons and at multiple cruising altitudes,” said Paul Williams, Professor of Atmospheric Science at Reading, who led the new study.

“This problem is only going to worsen as the climate continues to change.”

CAT is the most troublesome type faced by airliners because it is invisible and cannot be detected on radar.

Global warming is increasing the phenomenon by strengthening wind instabilities at high altitudes in the jet streams and by making pockets of rough air stronger and more frequent.

Even severe turbulence is all but incapable of threatening the survival of a commercial aircraft, however it can cause injury to those on board.

In June, 20 people were injured, including some with broken bones and head wounds, when a China Eastern Airlines flight from Paris to South West China struck heavy turbulence.

The overall number of casualties recorded globally each year is in the low hundreds, however experts believe this is due to under-reporting of minor injuries and the true number is significantly higher.

Last month the manufacturer Boeing announced it was preparing to test a new laser technology allowing pilots to detect CAT up to ten miles away, although given the 550 mph cruising speed of most passenger jets, this would only give about 60 seconds’ notice.

“Unless aviation meteorologists become better at forecasting patches of turbulence, passengers will face increased discomfort levels from in-flight bumpiness and an increased risk of injury,” said Professor Williams.

“Air travellers can expect the amount of time they spend flying through turbulence confined to their seats to double or maybe even treble on some routes.”

Published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, the study predicted that severe turbulence over North America will increase by 110 per cent from 2050, 90 per cent over the North Pacific and 60 per cent over Asia.

The model also include the first turbulence predictions for the Southern Hemisphere and tropical regions of the planet, estimating an increase in severe turbulence over South America of 60 per cent, and Australia and Africa of 50 per cent.

Aircraft are currently thought to spent about three per cent of their cruising time in light intensity CAT, and about 1 per cent in turbulence of moderate intensity.

Dr Manoj Joshi, who co-authored the research from the University of East Anglia, said: “This study is another example of how the impacts of climate change can be felt through the circulation of the atmosphere, not just through the increases in surface temperature itself.”

Divided US solar sector spars over trade relief at hearing.

U.S. solar manufacturers on Tuesday asked federal trade officials to impose tariffs on cheap foreign-made panels, clashing with companies who rely on those products to build low-priced projects that can compete with gas and coal.

(Reuters) - U.S. solar manufacturers on Tuesday asked federal trade officials to impose tariffs on cheap foreign-made panels, clashing with companies who rely on those products to build low-priced projects that can compete with gas and coal.

In a closely-watched case, the U.S. International Trade Commission is set to recommend measures to prop up the small domestic solar manufacturing industry after it ruled unanimously last month that producers have been harmed by imports.

It must deliver its report by Nov.13 to President Donald Trump, who will then decide how to proceed.

The outcome could have a major impact on the price of solar power in the United States and determine whether the renewable energy technology can compete with dominant fossil fuels.

Suniva and SolarWorld, which are both foreign-owned but manufacture panels in the United States, asked for four years of tariffs on all solar cells and panels made overseas, plus either a price floor on panels or an import quota.

“Tariffs alone will not remedy the serious injury you found,” Suniva attorney Matthew McConkey told the commission.

In documents filed last week, Suniva asked for a tariff of 25 cents per watt on solar cells and 32 cents per watt on panels. The manufacturer is also seeking a minimum price on panels of 74 cents a watt, nearly double their current cost. SolarWorld has asked for an import quota.

Existing tariffs on solar products from China and Taiwan have been insufficient to protect the domestic industry, Suniva said.

Suniva is majority owned by Shunfeng International Clean Energy and SolarWorld AG is based in Germany. Suniva filed for bankruptcy in April and soon after filed its petition with the ITC.

The Solar Energy Industries Association, the sector’s primary trade group, opposes Suniva’s petition.

SEIA argued on Tuesday that higher panel prices would hurt demand, impacting installation companies and manufacturers and leading to widespread job losses.

“These job losses are far, far in excess of any limited job gains the domestic cell and module industry might obtain based on optimistic projections,” SEIA attorney Matthew Nicely said.

SEIA suggested less radical remedies - technical assistance, job training programs, and a modest import licensing fee.

SunPower Corp Chief Executive Tom Werner testified that concerns about new tariffs had caused his company to lose “a multi-hundred million dollar opportunity” to rival First Solar Inc, which uses a technology not included in the trade case.

“We couldn’t offer price certainty and they could,” Werner said. SunPower is based in California but primarily manufactures panels in Asia.

Reporting by Nichola Groom; Editing by Sue Horton and Rosalba O'Brien

That rotten stench in the air? The smell of deadly gas and secrecy.

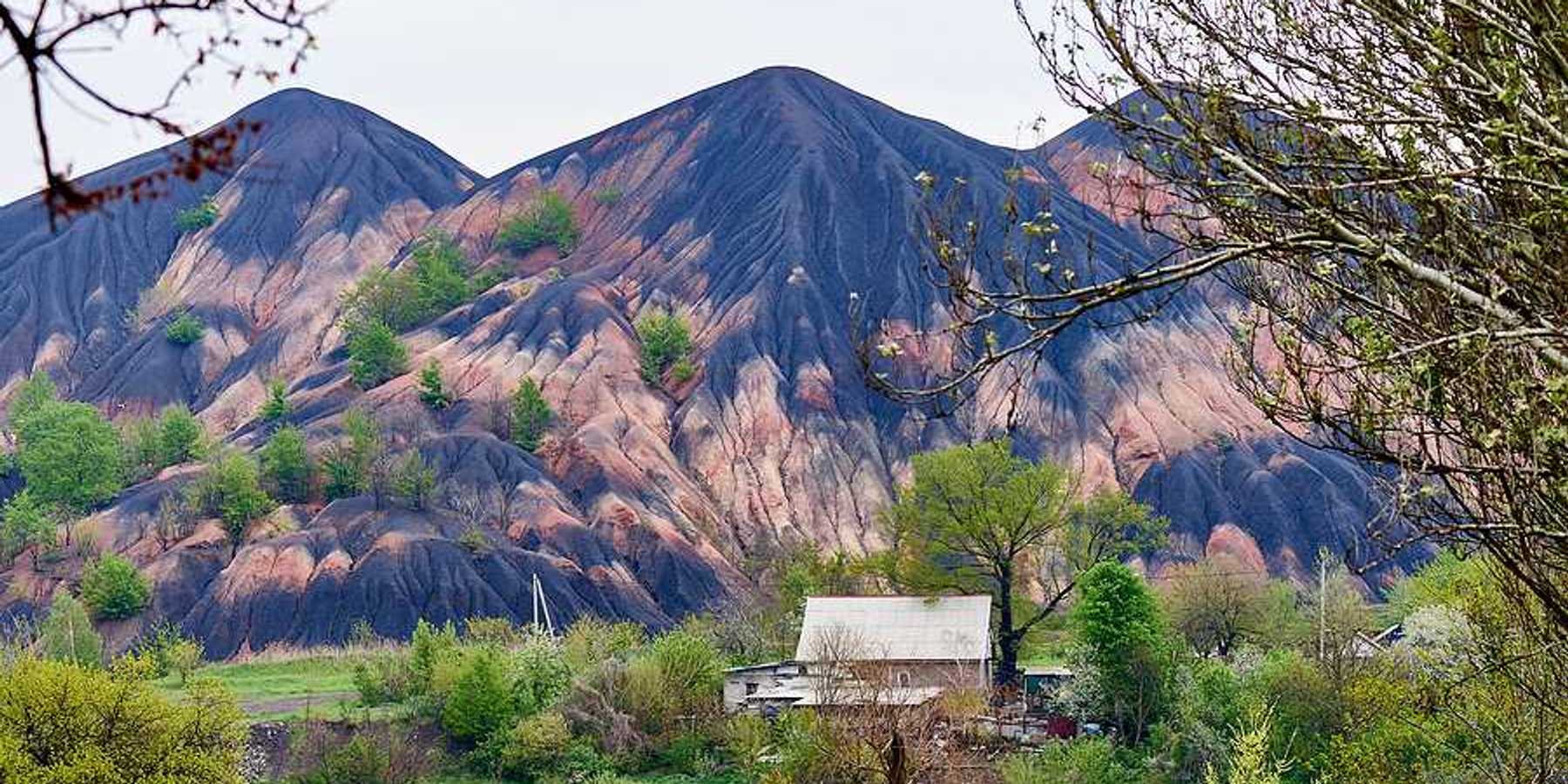

As the number of shale oil wells has soared in Saskatchewan, the risk of hydrogen sulphide leaks has multiplied. A year-long investigation reveals what the government and industry knew — and kept from the public.

NewsWorld

That rotten stench in the air? It’s the smell of deadly gas and secrecy

As the number of shale oil wells has soared in Saskatchewan, the risk of hydrogen sulphide leaks has multiplied. A year-long investigation reveals what the government and industry knew — and kept from the public.

Documents and information from whistleblowers disclose findings of failures in performance by oil and gas companies, including serious infractions, failed safety audits, daily H2S readings beyond provincial air quality standards and a death in 2014. (MARK TAYLOR FOR THE TORONTO STAR)

A gas flare tower west of Oxbow, now a common sight in the province. (MARK TAYLOR / FOR THE TORONTO STAR)

By ROBERT CRIBBStaff Reporter

PATTI SONNTAGMICHENER AWARDS FOUNDATION

P.W. ELLIOTTUNIVERSITY OF REGINA

ELIZABETH MCSHEFFREYNATIONAL OBSERVER

Sun., Oct. 1, 2017

OXBOW, SASK.—The two-storey cedar home where Shirley Galloway lives with her family was a solitary dot on the Saskatchewan prairie when they moved here 21 years ago.

The view from the front porch, once a landscape of rolling hills, horse pastures and lush river valley, has been transformed.

Today, Oxbow is surrounded by bobbing, black steel pump jacks and flare stacks burning off hydrogen sulphide and other dangerous gases that rise with the oil and trail off in ribbons of flame over green fields.

Late in the afternoon of Oct. 30, 2012, Galloway, a 53-year-old registered nurse, heard screams from the front yard.

Galloway dashed out to find a teenage family member vomiting and the air thick with the rotten-egg smell of sour gas — hydrogen sulphide (H2S).

Article Continued Below

Galloway, who trains oil workers to survive these same events, knew what to do.

She pulled the teen inside, grabbed an air monitor and held it out the door. The reading was off the dial — more than 100 parts per million — a level immediately dangerous to human health.

Saskatchewan’s oil boom has brought jobs for many. For others, it has brought fear, injury and one death.

The number of “fracked” wells in the Bakken shale oilfield alone increased from 75 in 2004 to nearly 3,000 in 2013, according to a 2016 paper by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. The promise of prosperity, similar to its southern neighbour North Dakota’s Bakken boom, has been embraced by a province struggling to diversify its economy.

A national investigation by the Toronto Star, the National Observer, Global News and journalism schools at Regina, Concordia, Ryerson and UBC has uncovered failures by industry and government to respond to — and warn the public about — the serious and sometimes deadly threat of H2S gas wafting across Saskatchewan.

Documents obtained through freedom-of-information requests and from whistleblowers — internal correspondence, meeting minutes, presentations and inspection reports — disclose findings of failures in performance by oil and gas companies, including serious infractions, failed safety audits, daily H2S readings beyond provincial air quality standards and a death in 2014.

Yet regulatory standards remain largely unchanged and H2S incidents and risks remain hidden from the public.

The teen overcome in Galloway’s yard eventually recovered but missed school for several days with nausea and headaches.

H2S can be an insidious killer.

Heavier than air, it tends to settle in ravines and valleys.

Registered nurse Shirley Galloway knew what to do when she found a family member vomiting amid the smell of sour gas. Galloway trains oil workers to survive these leaks. (DEREK PUTZ / GLOBAL NEWS)

Just above the level Galloway’s monitor detected — 100 parts per million — H2S causes olfactory paralysis, leaving a victim unable to detect the rotten-egg smell. Continued exposure at that level may cause death within 48 hours.

A person exposed to a highly concentrated plume of the gas — at 1,000 parts per million — may die rapidly from respiratory paralysis, or over the course of days, from an inflammatory reaction in the lungs.

Victims effectively suffocate.

The government issued no public warning after Galloway reported the plume at her home because “there was no evidence that this was a widespread failure.” But inside government and industry offices, documents indicate the seriousness of H2S issues that led to years of meetings, audits and proposed regulatory reforms.

On April 7, 2014, government and industry officials deliberated about releasing data that showed H2S “hotspots” across southeastern Saskatchewan.

“Government may be accused of hiding information,” the notes read. “Public will want to know: 1. What are the areas? 2. How is it managed? 3. How is the government making sure it’s managed?” one unnamed official told the meeting. “Are we creating a risk by not releasing this data immediately?”

Despite acknowledging “significant” public health risks from H2S, at least some officials present expressed concern about “sensitivity in this data (because) there are residents living in these areas.”

No release followed.

Three weeks later, government-proposed fines for emission breaches — up to $1 million in penalties — were rejected by two major industry groups. In a letter to the ministry dated April 29, 2014, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) and Explorers and Producers Association of Canada (EPAC) called the proposed penalties “unsuitable.”

A former ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of losing his current job in the industry, says “almost every amendment was being rejected.”

EPAC officials declined comment.

Terry Abel, CAPP’s spokesperson, said the letter was intended to explain that, “in some cases, fines aren’t appropriate at all … If there’s an unsafe operation, it should be shut down. It shouldn’t be operating. That’s the best way to ensure the public safety is protected.”

The proposed fines were dropped.

The next month, Michael Bunz, a 38-year-old salesman supplying chemicals to oil and gas facilities, lay in a shack 80 kilometres from the Galloway house, dead after being exposed to H2S.

The official incident report filed with the Ministry of the Economy, which regulates Saskatchewan’s oilfields, makes no mention of Bunz’s death.

The story of the Bunz family, who lost their son after he was exposed to H2S gas in Saskatchewan as well as others who have made narrow escapes.

These regulators “are really thinking about the economic health of the province,” says Emily Eaton, a professor at the University of Regina who has studied the relationship between the oil industry and the government. Eaton is a member of the Corporate Mapping Project.

A shift in 2012 — from the Ministry of Energy and Resources to a new Ministry of the Economy tasked with regulating natural resource extraction and promoting economic development — changed the ministry’s role from watchdog to partner, she says.

“They’re thinking about returns on investment … The industry should really be regulated by those that have the interests of the environment first.”

Ministry field staff raised this concern at a meeting on July 1, 2015, between government and industry.

“The role of the regulator needs to be adjusted,” the meeting’s minutes read. “The regulators are acting as consultants in some situations. The role of the regulator is to enforce the rules and if the rules are clear and if enforcement is consistent and clear then, ‘cultural’ changes can be made.”

In its statement, the ministry rejects criticisms of conflict of interest or lax enforcement.

“Within the Ministry of the Economy, the petroleum and natural gas division carries out industry regulation,” wrote the department’s spokeswoman, Deb Young. “It is not involved in investment attraction, royalty and tax assessment and land sales. It is solely focused on well, facility and pipeline regulation.”

That regulation has not included fines or prosecutions.

The ministry has not issued a single fine against any industry company “for well over a decade,” Doug MacKnight, assistant deputy minister responsible for petroleum and natural gas, said in an interview.

“Generally, we don’t have to resort to that,” he said. “It’s usually just a notice to the operator to bring themselves into compliance.”

Prosecutions have also not been part of the ministry’s enforcement practices because non-compliance was dealt with “through other enforcement actions,” reads the ministry’s statement.

Other enforcement actions include increased inspections and staff, high-tech equipment for detecting emissions and a $69-million inspection reporting database (which can’t be accessed by the public).

Still, complaints of illness from residents and workers continue.

Lori Erhardt, a minister and musician, believes various health problems are related to gas in the area neare her home in Oxbow, Sask. (MARK TAYLOR FOR THE TORONTO STAR)

“I will sometimes get faint, like I will fall over and I have to find a seat quickly,” says Lori Erhardt, a United Church minister and musician living near Oxbow who believes her chronic illness is related to emissions.

“I have had a variety of diagnoses, most of them end with “i-t-i-s,” which means inflammation … If something gets inflamed, if it’s blood vesicles, you feel it through your body.”

Among the five years’ worth of documents obtained by this investigation is an April 2012 PowerPoint presentation to CAPP members by the director of the province’s petroleum and natural gas division. It includes a map of southeastern Saskatchewan showing a bloom of red and orange circles, labelled “critical sour gas locations.”

Sources say ministry staff pushed to make the data public but senior government officials said “there’s no goddamn way that is going to be released,” according to the former ministry source.

“There’s an institutional reluctance to make this information public,” he said. “The public should be able to see all the information that legislators have identified as public information such as sour gas and inspection reports.”

"'I will sometimes get faint'"

LORI ERHARDT

UNITED CHURCH MINISTER AND MUSICIAN LIVING NEAR OXBOW WHO BELIEVES HER CHRONIC ILLNESS IS RELATED TO EMISSIONS

The ministry statement says the map was never approved for release because some data was out of date, not comprehensive and “could provide the public and industry with a false understanding of risk associated with a particular well or facility.”

After the Galloway incident, the ministry inspected 11 oil and gas facilities. All failed “with serious infractions,” including releasing H2S at lethal levels “that may be exceeding 150,000 (parts per million),” Brad Herald, CAPP’s Saskatchewan operations manager, wrote to the board of governors in December 2012.

Those levels are 150 times the amount that could cause instant death.

Among the causes: “It is believed that inadequate training on the installation and operation of equipment is … contributing to the air quality issues.”

CAPP’s Abel said in an interview the “unsafe” facilities responsible for those breaches should not have been operating.

“They should have been shut down,” he said. “When you follow the rules, processing and production of sour gas is absolutely safe. If you don’t follow the rules, it can pose a health risk. So ultimately, those operators at those facilities were responsible.”

Neither CAPP nor its industry partners made the health risks public. And no ministry fines or prosecutions followed.

Internally, CAPP quickly mobilized to develop a public relations and damage control plan:

“There are growing public concerns regarding the air quality issues in southeast Saskatchewan,” Herald wrote, noting a petition and a Facebook page.

“The Ministry fields one to two public complaints concerning odours per week and the issue is garnering increasing political attention . . . This has the potential to become a broader industry reputation/social license concern and warrants immediate attention by operators in the region . . . Communications is preparing key messages in the event that there is media profile.”

CAPP received a warning the next month after consulting a scientist with expertise on managing toxic substances, internal emails show. The scientist expressed disappointment noting that H2S failures were “so easy to avoid.”

The scientist urged the industry lobby group to develop and implement a new code of practice to control dangerous emissions and get ahead of the problem by publicly denouncing unacceptable practices. The scientist also recommended that the industry group pressure the province to step up inspections.

The ministry, in meetings with industry, proposed similar reforms.

In a letter sent in March 2013 then-energy minister Tim McMillan — now president and CEO of CAPP — warned companies to meet “compliance obligations” or face “escalated enforcement, penalty and/or prosecution.”

Ministry and industry met four times between 2012 and 2014 to plot strategy, including emergency planning zones, a public communications document, a code of practice and a licensing regime for high-risk, single-well batteries.

Those plans were never adopted, a ministry statement confirms.

“Instead, the Ministry chose to take a risk-based approach to managing the sour gas issue that included increased field inspections and improved data collection.” Eighteen wells that had been venting sour gas were ordered to be “shut-in” in 2012/2013.

Michael Bunz, who died from exposure to H2S gas. (DEREK PUTZ / GLOBAL NEWS)

From 2013 to the summer of 2014, the ministry began implementing “an aggressive inspection and enforcement schedule to reduce sour gas emission” that included suspension orders against 30 facilities owing to “H2S management issues,” the statement reads.

During that effort, H2S would claim its most high-profile victim in Saskatchewan.

Michael Bunz, a salesman for Nalco Champion, died on May 22, 2014, while taking samples in a shed located in a provincial park between Carlyle and Kipling. A valve on the tank broke and oil, water and H2S spewed into his face.

An incident report submitted by the tank’s owner, Harvest Operations Corp., states simply: “Spill occurred as a result of a failed valve.”

Dianne and Allan Bunz visit the gravesite of their son, Michael, who was killed by H2S gas while working near his home in Wawota, Sask. "We knew aout H2S but I wasn't aware that he was going on site and doing the testing," Dianne says. (MARK TAYLOR FOR THE TORONTO STAR)

Nowhere does it mention Bunz’s death.

Instead, his death is marked by a gravestone in a small cemetery near Wawota, where the father of two young daughters lived a few doors away from his parents, Dianne and Allan.

The black, polished stone, with an image of Bunz wearing his Saskatchewan Roughriders jersey and hat, calls him “Bunzy” and reads: “In loving memory of Emma and Olivia’s Daddy.”

“He didn’t really talk about those dangers,” Dianne says. “We knew what it’s like to work in the oil industry. My husband did for 20 years. We knew about H2S but I wasn’t aware that he was going on site and doing the testing.”

The summer before he died, Allan drove his son to the Nalco office to quit. Michael’s brother-in-law, who had worked there, had left and “things had been pretty tough,” Michael said, marked by long days and heavy workload.

“He was going to hand his company truck in, and his boss was there … he talked (Michael) out of it,” Allan says. “This company wanted him because he never ever phoned in sick or anything. He’d just go to work. And they offered him more money, so he stayed.”

Nalco Champion is facing three charges under the province’s occupational health and safety legislation for failing to provide Bunz with a respirator and to ensure he entered a dangerous situation with a second worker. A conviction would result in a fine.

The family says they were told by Nalco that the concentration of H2S in the fluids was estimated at 40,000 parts per million, more than enough to bring near-instant death.

The company sent reporters a written statement, declining further comment.

“We remain deeply saddened by the loss of our colleague, Michael Bunz. The safety of our associates, customers and communities is vitally important, and we remain committed to our robust safety policies, protocols and training programs, which include those related to hydrogen sulfide,” it reads.

Allan, who spent most of his working life in the oil industry, says he learned more about H2S protection when he worked on a pig farm.

“Every person had to wear an H2S monitor. And I’m talking about the pig industry,” he says. “To me, they were protecting us … more at this simple small hog operation in Saskatchewan than the oil industry ever did the entire time I was working out there.”

The couple reviewed the records documenting years of discussions between government and industry about public health risks and failed audits that were never made public. The couple called it “devastating.”

“I go to work every day and I drive down the highway and I talk to my son sitting beside me,” says Allan. “I say to him “tough day there, son” and I tell him how I feel . . . I feel him sitting there beside me.”

Trina Hansen was clearing a pipeline near Carlyle, Sask., when she breathed in H2S. “Your first reaction is to inhale. When it hits your face, you breathe it in." (DEREK PUTZ / GLOBAL NEWS)

How often H2S incidents happen or happened in Saskatchewan remains a mystery.

Officially, ministry officials count one death and five “documented incidents where a member of the public was exposed to unsafe levels of sour gas near a well or facility site.”

None of them triggered a public statement by the government.

“There was no need for public notification since the incident was quickly dealt with at the site,” reads the ministry statement.

But after dozens of interviews it is clear that H2S incidents involving residents are more common but go unreported or are not recorded properly. This is also true for workers in the oilfield.

Only months after Bunz died, Trina Hansen, an oilfield worker and part-time voice actress, was clearing a pipeline near Carlyle, Sask.

“I could have died,” she says. “It’s almost like you could feel like a heavy air hit your face. It’s a really weird feeling. Your first reaction is to inhale. When it hits your face, you breathe it in. It’s the weirdest thing. You don’t think to hold your breath. It happens so fast. I stumbled backwards. I was so shocked.”

Disoriented, Hansen got back in her truck and drove a couple of kilometres until she noticed she was losing her peripheral vision.

“There were white sparkles, iridescent, swirly, super-shiny and bright. I jumped out and started feeling nauseous and couldn’t breathe very well. I was trying to catch my breath and dry heaving. My head started pounding.”

"'I could have died'"

TRINA HANSEN

AN OILFIELD WORKER AND PART-TIME VOICE ACTRESS EXPOSED TO H2S

Hansen, suffering debilitating headaches, nausea and sickness, lost her voice for two weeks.

“This happened three years ago and I still have a hard time catching my breath if I talk too fast. I’m very short of breath. I’ve never in my life felt like that. It was horrible.”

Her voice has changed for good — it is far deeper and lower than before.

“I do a cartoon on APTN network and they said my voice totally changed. It changed two octaves pretty much. It used to be high and now it cuts out.”

Hansen never reported the incident, fearing she would lose her job.

“Nobody wants to say anything. We know it’s bad and dangerous. But no one wants to raise a fuss. And being a woman and trying to prove yourself out there, I never claimed WCB (Workers Compensation Board). The economy went down and I have to pay off debt with my trucking money.”

Four months after Bunz’s death, a secret ministry report listed 161 facilities “that may be in violation of (the ministry’s) sour gas emission control.”

The catch: “time and resources required to investigate and verify violations would take all available field officers over a year.”

In 2014, inspections of 60 suspicious wells in 2014 turned up 36 — more than half — that were leaking so badly they had to be shut down.

Another audit found 11 out of 12 facilities failed inspection “due to H2S venting” and found 29 locations that are too close to facilities with high levels of H2S concentrations. Of the 1,352 active sour gas facilities, only 421 — 31 per cent — had “proper emission control systems.”

“Almost every site had improper gas measurement,” the report reads. “Discovered major contamination at two facilities as a result of spill which were not reported” to the ministry.

The ministry believes that the H2S issue is under control, saying air quality standards are being met and that inspections confirm that companies’ sour gas management practices have improved. Today 27 full-time inspectors are responsible for the province’s 126,000 wells and its estimated 118,000 kilometres of pipelines and flowlines, operating with a budget of $3.9 million.

In 2016-17, ministry staff inspected 18,340 wells, facilities and pipelines.

Last month, a team of researchers from Harvard and Northeastern Universities collected data in collaboration with this investigation using the same instruments employed by ministry inspectors to detect emissions invisible to the naked eye.

“In my experience measuring oil and gas activities in Texas, what struck me was that about a third of the sites we looked at had what we believed to be fugitive emissions and the high density of pump jacks,” says Lourdes Vera, a doctoral student in environmental sociology at Northeastern University.

Drew Michanowicz, a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard University’s School of Public Health who led the survey in Saskatchewan, said about one in five of the facilities they visited showed black smoke rising from the flaring stacks of production facilities.

“If there is black smoke, there is particulate matter that if inhaled is certainly associated with human health effects,” he said. “If sources of these air pollutants are constantly impacting individuals where they live, work and play, there is the worry that they are experiencing health effects.”

A pump jack is surrounded by batteries near Roche Percee., Sask. (MARK TAYLOR FOR THE TORONTO STAR)

In interviews with landowners and records in the government database, this investigation has found recent H2S accidents, including three people who say they were sickened by H2S clouds near their homes in the past year. One said they required hospitalization after a near-fatal incident.

In January, more than four years after the H2S incident in Galloway’s front yard, she and her husband were driving home when they encountered a plume of what she believes was H2S gas.

She fell ill and stayed home for three days.

“I’ve had arrhythmias, really wicked headaches … I’ve had bouts of nausea. I wake up at night and have heart palpitations.”

Galloway wrote to public officials demanding a response.

There were no consequences or fines as a result. And no official report of an incident anywhere near the Galloway property that day was filed.

That, says Galloway, is just the way it works in Saskatchewan.

“As a person living in the middle of the oilfield, you have no protection. The government doesn’t care. Your MLA doesn’t care. The oil companies don’t care.”

Unprecedented collaboration behind the project

During the past nine months, an unprecedented collaboration of more than 50 journalists and editors from three Canadian media outlets, four journalism schools and a think tank have worked to chronicle the hidden price of oil in Canada.

Collectively, reporters examined thousands of industry and government documents, analyzed terabytes of data and delved into dozens of freedom-of-information requests.

“The project started with the people,” says Patti Sonntag, a managing editor in the New York Times’ news services division, who launched the project with a grant from the Michener Awards Foundation. Following a tip from a colleague at the Corporate Mapping Project, she did some research and reporting in Saskatchewan last fall.

Working with the previous year’s Michener winner, Toronto Star journalist Robert Cribb, Sonntag created a team of students at the Ryerson, Concordia and UBC journalism schools. Concordia University’s Department of Journalism volunteered to act as host and headquarters for the project.

University of Regina students reported on the ground locally, shot video and developed sources, while students at the other universities aggregated and analyzed data and interviewed experts.

“We’re pulling these four different schools from across the country and looking at it from all different aspects,” says Janelle Blakley, a University of Regina student reporter whose team mapped spills data and met local farmers and residents. “This collaboration allowed us to really dig into it, where all schools were pulling apart different pieces of it and then coming back and putting it all together.”

The significance of the data quickly drew intrigue. What emerged was a picture of a few dedicated regulators — and even some industry leaders — who tried to introduce greater accountability, but these efforts were ultimately overwhelmed by larger forces.

“You start to understand these figures really do play a huge role in dictating the direction of the Canadian economy and that plays out in the lives of everyday Canadians,” says Lauren Kaljur, a graduate of UBC’s master of journalism program who has been investigating the concentration of corporate power in Saskatchewan’s oil and gas industry since the beginning of 2017.

To Matthew Gilmour, a recent journalism graduate at Concordia University, after spending months populating spreadsheets and ledgers, “there’s the human moment where you realize it’s not just a pocketbook story. It’s a human story. And people’s lives are affected.”

The work continued past the end of the semester in April 2017, with students working alongside veteran reporters at the Star, the National Observer and Global News to shape the stories, seek comments from all sides and publish hundreds of pages of government and industry records, detailing concerns about potentially deadly gas emissions for the first time.

Writers/Reporters:

Robert Cribb, The Toronto Star

Patti Sonntag, Michener Fellow

P.W. Elliott, University of Regina

Elizabeth McSheffrey, The National Observer

Data and documentation journalist:

Michael Wrobel, Concordia University

Researchers:

Jennifer Ackerman, University of Regina

Madina Azizi, University of Regina

Janelle Blakley, University of Regina

Cory Coleman, University of Regina

Mike De Souza, The National Observer

Josh Diaz, University of Regina

Brenna Engel, University of Regina

Matthew Gilmour, Concordia University

Celine Grimard, University of Regina

Jared Gottselig, University of Regina

Lauren Kaljur ,University of British Columbia

Rebbeca Marroquin, University of Regina

Matthew Parizot, Concordia University

Katie Doke Sawatzky, University of Regina

Michaela Solomon, University of Regina

Kyrsten Stringer, University of Regina

Caitlin Taylor, University of Regina

Steph Wechsler, Ryerson University

Faculty Supervisors:

P.W. Elliott, University of Regina

Trevor Grant, University of Regina

Series Producer:

Patti Sonntag, Michener Fellow, based at Concordia University

Institutional Credits:

Concordia University, Department of Journalism

Ryerson University, School of Journalism

University of British Columbia, Graduate School of Journalism

University of Regina, School of Journalism

Global News

The Michener Awards Foundation

Corporate Mapping Project

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Parkland Institute

University of Victoria

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council

Watch the televised investigation: Sunday and Monday on Global National at 5:30 CT/MT/PT & 6:30 ET/ATRobert Cribb can be reached at rcribb@thestar.ca

DELIVERED DAILY

The Morning Headlines Newsletter

Subscribe

The Toronto Star and thestar.com, each property of Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, One Yonge Street, 4th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5E 1E6. You can unsubscribe at any time. Please contact us or see our privacy policy for more information.

More from the Toronto Star & Partners

LOADING

LOADING

About

Contact Us

Feedback

thestar.com

Toronto Star Newspaper Ltd.

Advertising

Initiatives

© Copyright Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd. 1996 - 2017

Privacy PolicyTerms and Conditions

The Toronto Star and thestar.com, each property of Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, One Yonge Street, 4th floor, Toronto, ON, M5E 1E6

One of the clearest signs of climate change in Hurricanes Maria, Irma, and Harvey was the rain.

Warmer temperatures are increasing the energy and moisture available to hurricanes.

As Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria plowed through unusually warm oceans this summer, each one broke records, startling even the scientists who study extreme weather.

“All of these storms went through a period where they gained strength quickly,” said James Kossin, an atmospheric scientist at the NOAA Center for Weather and Climate Prediction. “That was alarming.”

The intensity of Hurricane Maria, which made landfall on Puerto Rico as a Category 4 storm on September 20, was part of why it was so devastating to the island and its weak infrastructure, leaving Puerto Ricans in a humanitarian crisis.

But this year’s intense Atlantic storm season had another element tying its biggest events together: a monstrous, and sometimes deadly, amount of rain.

Images of the flooded metropolises of Houston, Jacksonville, and San Juan with overtopped dams, billowing sewage, and flooded homes show that torrential rain can be one of the most devastating consequences of hurricanes, especially in urban areas where concrete makes it harder for water to drain and where people can drown.

Scientists say the extreme rainfall events that feed these floods are on the rise for many parts of the world, and this year’s hurricanes fit that trend. In particular, rising temperatures in the ocean and the air alongside booming construction in vulnerable areas are fueling the increased risk from massive deluges.

Of the seven hurricanes this year so far, Harvey, Irma, and Maria stand out not just for the amount of rain they dropped, but for how fast they dished it out.

Why hurricanes under warmer conditions can dump so much rain

Downpours go hand in hand with hurricanes, since the cyclones are powered by evaporating and condensing moisture.

Warm ocean waters provide the fuel for hurricanes, and warm air causes the water to evaporate. This moisture-laden air then precipitates as rainfall during a hurricane, dissipating the heat energy from the water.

“Tropical cyclones are very, very good at converging a whole lot of heat in one place at one time,” said Kossin.

Air can hold about 7 percent more water for every degree Celsius increase in temperature, Kossin explained.

That means warmer air and warmer water could lead to larger, more intense hurricanes, which in turn lead to more rainfall. (The Saffir-Simpson scale only accounts for windspeed, but precipitation is closely linked to a storm’s intensity.) Scientists are studying these links to understand how future storms will respond to these conditions.

“Hurricanes live and die by the amount of rainfall they make out of moisture,” said George Huffman, a research meteorologist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

But where that water lands depends on the speed and the course of the storm, and not all areas are equally vulnerable.

“We know that in particular that [the regions around] Houston, Louisiana, and Florida are prone to some of the most extreme precipitation events in the United States,” said Sarah Kapnick, a researcher at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. “We do see signs of precipitation extremes increasing in these regions.”

It’s challenging to make direct comparisons between extreme rainfall events since their weather systems (e.g., hurricanes, thunderstorms) behave differently, so scientists draw on several benchmarks depending on the situation.

These include the peak rate of rainfall, total volume of rain, the three-day average rainfall, and the maximum depth of rainfall. And all of these are separate from flooding, which is governed by local geography and how people use land, in addition to the rates and total amounts of rain.

“There is a difference between a 100-year rain event versus a 100-year flood event,” Kossin pointed out.

Harvey was able to dump an extraordinary quantity of rain because of how it held still over Houston

Hurricane Harvey hovered over the Gulf Coast in late August and dumped 33 trillion gallons of water on US soil, according to some estimates, and is now the wettest storm in US history.

“When a storm stalls, that has more to do with the larger scale flow fields it’s sitting in,” said Kossin. “That was just very, very bad luck.”

The total volume of rain is easier to calculate when a storm remains over a fixed area, but it much harder to suss out when hurricanes remain mobile and dump water over a wide swath of land and ocean.

NASA’s satellite measurements reported rainfall rates from Harvey as high as 5.8 inches per hour (meteorologists define “heavy rain” as greater than 0.3 inches per hour), while the National Weather Service showed that a ground-based rain gauge in Nederland, Texas, reported 60.58 inches of rainfall, a new record.

Meteorologists still have to vet this number, but if confirmed, it would best the previous record — 52 inches in Hawaii from Hurricane Hiki in 1950 — by 8 inches.

The US Geological Survey reports that flooding causes an average of $6 billion in damages and 140 fatalities each year. And this year was not an average year, with Harvey alone costing upward of $180 billion and killing more than 75.

The waters from flooding can linger for days, causing injuries, spreading disease, and hampering relief efforts. The majority of Harvey’s victims drowned after the storm, while others were delayed from life-saving care. In one case, a woman died from a flesh-eating bacterial infection after falling into the festering Harvey floodwater in her house.

Irma’s peak rain was over Cuba

Hurricane Irma, meanwhile, set a record for its sustained intensity.

One hour of 30-second #GOES16 vis imagery as Hurricane #Irma made landfall in the Florida Keys as a cat 4 with sustained winds of 130 MPH. pic.twitter.com/SWIMtbIqAP

— NASA SPoRT (@NASA_SPoRT) September 10, 2017

“Irma was a complete standout: 185 mph and stayed there for a day and half,” Kossin said. “These storms do not stay there that long.”

This intensity was matched with a firehose of rain, dumping water at 10.8 inches an hour, reaching depths of 20 inches in Cuba and 15.8 inches in Florida.

The downpour led to flooding from 23 rivers and creeks in Central and North Florida, forcing highways to close. The state reported at least seven deaths from drowning.

In Cuba, Irma’s storm surge overtopped the Havana seawall, while unrelenting rain turned the capital’s streets into rivers, killing at least 10 people .

Maria took direct aim at Puerto Rico and then regained strength

With tropical force winds reaching 230 miles from its center, Hurricane Maria completely engulfed Puerto Rico as it bisected the 100-mile wide island, picking up steam again one it was clear.

Satellite measurements already show that it poured as much as 6.44 inches of rain per hour and has left Puerto Rico shrouded in darkness.

Hurricane #Maria's Torrential Rainfall in #PuertoRico Measured By GPM IMERG 9/17/17 - 9/21/17 https://t.co/814C281kvu pic.twitter.com/CRcnMXJ5xk

— NASA Precipitation (@NASARain) September 21, 2017

The Cordillera Central mountain range that forms the spine of the island of Puerto Rico acted as a juicer for Hurricane Maria, Huffman explained, rapidly squeezing out 20 to 36 inches of rain from the cyclone.

In *less than one day* parts of Puerto Rico have received 24-36"+ of rain.

For context: Houston had 32" in *three days* during Harvey. Wow. https://t.co/5dWnxtEPTp

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) September 21, 2017

Perhaps the worst blow from Maria was the 160 mph winds that knocked down 80 percent of the island’s power transmission lines and 85 percent of its cellphone towers, leaving people in the dark and struggling to contact each other. But the flooding from rainfall has been a hazard too, including threatening to breach Guajataca Dam in the Western part of the island, forcing hundreds to evacuate.

At least 18 fatalities have been reported in Puerto Rico so far, including two police officers who drowned.

The climate signal in deluges like these is emerging

No single weather event — even an extreme one — can be “caused” by climate change, as Vox’s David Roberts has explained in detail. And when talking about hurricanes, researchers are quite hesitant to even estimate how much climate change is to blame. Huffman said he’s not yet sure if this storm season is “unprecedented” in its ferocity.

However, rising average temperatures are definitely an important element of huge storms like Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

Warmer temperatures are driving sea level rise, which is increasing risks from the storm surges that often herald hurricanes.

Increasing heat is also warming up the ocean, and hotter air holds onto more moisture, increasing the available energy for hurricanes.

And independent of cyclones, extreme rainfall events are on the rise.

Kapnick noted that even individual rain storms can be overwhelming, like storm that drenched Baton Rouge last year with 31.39 inches of rain and three times the volume of water of Hurricane Katrina throughout Louisiana in 2005.

As the chart below shows, the amount of rain from a once-in-every-30-years rainstorm like the one that immersed Baton Rouge has gone up due to warming:

“In this region where we have known precipitation extremes, we have been able to detect an increase in precipitation extremes due to a warming climate,” Kapnick said.

And scientists are getting better at figuring out when the torrential downpours are coming.

“If you pay attention, we’ve had a really remarkable series of forecasts,” said Huffman. “For Irma, we knew four to five days in advance that there would be a sharp right turn. Twenty years ago, you wouldn’t have dreamed of doing that.”

“Everything we see is consistent with what we expect climate change to do,” Kossin said.

Instruments sometimes can’t stand up to the extreme weather they’re trying to measure

Huffman explained that researchers aim to combine different instruments to get a robust handle on rainfall.

“The gold standard is rain gauges because they physically collect the rain,” said Huffman.

The next option is ground-based radar, which covers a wider swath of the weather than rain gauges, but less directly measures rain.

But take a look at what happened to a weather radar station in Puerto Rico:

Wow, this is TJUA San Juan, Puerto Rico radar back in March, and now after Hurricane Maria. Incredible. Recent photo courtesy of @NWSSanJuan pic.twitter.com/WFzIxZBbGn

— Bryce Kintigh (@stormchasrbryce) September 24, 2017

This illustrates part of the challenge of attaching numbers to extreme weather events. Many of the systems used to track them are also vulnerable to them, leaving only indirect figures and estimates.

What’s more, both rain gauges and ground-based radar have limited ranges, leaving vast stretches of ocean where hurricanes spend most of their existence unmeasured. And when a hurricane does make landfall, gales can knock them down.

“We don’t really have anything on the surface [of the ocean] to tell us the details,” said Huffman. “When the chips are really down, sometimes satellites are the only choice.”

That means the full accounting for the rainfall from Harvey, Irma, and Maria could take months to deliver as meteorologists piece together their models with the measurements they have.

However, scientists are eagerly waiting for the dust to settle so they can confirm their suspicions about the record-breaking storms this year. The American Geophysical Union added a last-minute session for researchers to present their findings on Harvey and Irma at their December meeting.

“There’s going to be a tremendous amount of research coming out in the next few months,” Kapnick said.