nitrates_and_nitrites

Power plants get two-year reprieve for parts of wastewater rule.

Power plants won’t have to meet new limits until 2020 on toxic wastewater that comes from using air pollution control systems and transporting bottom furnace ash, the EPA announced.

From Daily Environment Report™

Turn to the nation's most objective and informative daily environmental news resource to learn how the United States and key players around the world are responding to the environmental...

By Amena H. Saiyid

Power plants won’t have to meet new limits until 2020 on toxic wastewater that comes from using air pollution control systems and transporting bottom furnace ash, the EPA announced Sept. 13.

The Environmental Protection Agency said it was postponing by two years compliance dates that would be required of more than 1,000 power plants nationwide, as it reconsiders how strictly it should limit those two sources of wastewater.

The postponement, requested by electric power utilities, applies to new Obama-era limits on wastewater generated by transporting bottom ash and by operating flue gas desulfurization (scrubber) units used to capture sulfur dioxide emissions from burning petroleum coke and coal.

Bottom ash transport wastewater refers to the water that power plants use to collect, cool, and convey ash and other slag from the bottom of a boiler to other parts of the utility for treatment.

These two sources of wastewater would make up 87 percent of the toxic pollutants removed by power plants, if the agency had chosen to implement the 2015 Obama rule as finalized.

The agency’s final unpublished rule follows public comments submitted on a proposal to postpone the 2015 rule’s compliance deadlines for all six categories of wastewater containing arsenic, selenium, nitrates, mercury, zinc, and other pollutants that power plants nationwide discharge. The rule will take effect upon publication in Federal Register.

Four Other Waste Streams Unaffected

The compliance deadlines for the two waste streams will be pushed back to Jan. 1, 2020. The rule’s deadlines for the four other sources of toxic wastewater—fly ash, mercury controls, gasification, and coal ash landfills—will still start Jan. 1, 2018.

A national industry group representing power plant operators, including subsidiaries of Ameren Corp. and American Electric Power, sought a deadline extension because the EPA is revising parts of a 2015 rule setting effluent limits for technology they would be required to use to treat the wastewater (RIN: 2040-AF14). The industry had pushed for the rewrite, arguing that the EPA used outdated and incomplete data to set standards for these two waste streams.

American Electric Power didn’t respond to Bloomberg BNA’s request for comment. The Edison Electric Institute, which represents investor-owned utilities, had commented on the postponement at a July 31 hearing at EPA headquarters. At that time, Rich Bozek, the institute’s director of environmental and health and safety policy, urged the EPA to postpone the deadlines for the two waste streams.

“Without a postponement, electric companies will continue to invest millions of dollars to plan for compliance with a rule that ultimately may change significantly,” Bozek said. “That would be a waste of electric company and customer resources, and it would force electric companies to make decisions about generation fleet investments and closures based on incorrect and incomplete information.”

Delay Expected

Environmental groups opposed to the agency’s decision to rewrite the 2015 rule weren’t surprised by the postponement. They already are involved in suing the EPA over its initial decision to reconsider the rule without public comment.

“EPA has chosen to delay two of the most significant sources of toxic pollutants,” Casey Roberts, a senior attorney with Sierra Club, told Bloomberg BNA Sept. 13.

The Sierra Club has received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable organization founded by Michael Bloomberg, founder of Bloomberg L.P. Bloomberg BNA is an affiliate of Bloomberg L.P.

To contact the reporter on this story: Amena H. Saiyid in Washington at asaiyid@bna.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachael Daigle at rdaigle@bna.com

For More Information

The EPA final rule postponing compliance is available at https://src.bna.com/swi.

Copyright © 2017 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Can American soil be brought back to life?

A new idea: If we revive the tiny creatures that make dirt healthy, we can bring back the great American topsoil. But farming culture — and government — aren't making it easy.

Four generations of Jonathan Cobb’s family tended the same farm in Rogers, Texas, growing row upon row of corn and cotton on 3,000 acres. But by 2011, Cobb wasn’t feeling nostalgic. Farming was becoming rote and joyless; the main change from one year to the next was intensively planting more and more acres of corn and soy, churning up the soil and using ever more chemical fertilizers and herbicides to try and turn a profit.

“I’d already had the difficult conversation with my dad that he would be the last generation on the farm,” Cobb said.

While looking for a new job, Cobb stopped into a local office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture to pick up some paperwork. That day, the staff was doing a training session on soil health. He stayed to watch and was struck by a demonstration showing a side-by-side comparison of healthy and unhealthy soils.

A clump of soil from a heavily tilled and cropped field was dropped into a wire mesh basket at the top of a glass cylinder filled with water. At the same time, a clump of soil from a pasture that grew a variety of plants and grasses and hadn’t been disturbed for years was dropped into another wire mesh basket in an identical glass cylinder. The tilled soil–similar to the dry, brown soil on Cobb’s farm—dissolved in water like dust. The soil from the pasture stayed together in a clump, keeping its structure and soaking up the water like a sponge. Cobb realized he wasn't just seeing an agricultural scientist show off a chunk of soil: He was seeing a potential new philosophy of farming.

“By the end of that day I knew that I was supposed to stay on the farm and be part of that paradigm shift,” Cobb said. “It was that quick.”

The shift he's talking about is a new trend in agriculture, one with implications from farm productivity to the environment to human health. For generations, soil has been treated almost as a backdrop — not much more than a medium for holding plants while fertilizer and herbicides help them grow. The result, over the years, has been poorer and drier topsoil that doesn’t hold on to nutrients or water. The impact of this degradation isn’t just on farmers, but extends to Americans’ health. Dust blowing off degraded fields leads to respiratory illness in rural areas; thousands of people are exposed to drinking water with levels of pesticides at levels that the Environmental Protection Agency has deemed to be of concern. The drinking water of more than 210 million Americans is polluted with nitrate, a key fertilizer chemical that has been linked to developmental problems in children and poses cancer risks in adults. And thanks to some modern farming techniques, soil degradation is releasing carbon—which becomes carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas—instead of holding on to it. In fact, the United Nations considers soil degradation one of the central threats to human health in the coming decades for those very reasons.

Now, some farmers and soil scientists are realizing that for the health of both people and farms, the most important thing you can do is look at soil differently—seeing topsoil as a living thing itself, which can be tended and even improved. Good soil is alive with a host of delicate organisms, many of them microscopic, producing structure and nutrients. As long as they’re thriving, soil can better absorb and retain water and feed plants and control pests. But when they die off, because they’ve been churned up and exposed to the sun and air or smothered with chemicals, the soil gradually becomes little more than powdered minerals.

Science and farming techniques have been evolving—in part thanks to the Agriculture Department’s Natural Resource Conservation Service, where Cobb saw that demonstration in 2011 that changed his worldview. But the change isn’t coming easily. Even as some farmers move toward more holistic soil management, they’re running into friction–from the culture of farming, from the business of agriculture and—ironically—from some federal policies that encourage them to stick to the same old farming approach that got them here.

AMERICA USED TO be famed for its rich and fertile topsoil. Prairie and forests were virtually untouched when settlers first started dividing land into fields across the Southeast and Midwest, making for rich dark soil in which to grow food and fiber.

Since the invention of the plow, farming has focused on disrupting the soil to make it productive. Most farming methods, whether conventional or organic, are based on “tillage” – the premise that to plant crops and control weeds and other pests, the soil must be broken up and turned over, then amended with chemical fertilizers or organic compost to boost fertility. And it worked for a long time.

But tilling, it turns out, kills off many of the microorganisms that build the soil. It churns up their habitat and exposes them to air; it also makes it easier for soil to be washed off the land by rain and wind. Over time, the damage has built up: More than 50 percent America’s topsoil has eroded away. In areas of the Southeast, the country’s original breadbasket, it’s almost all gone.

Soil, at its base, is 50 percent gas and water, and roughly 45 percent minerals such as sand, silt and clay. The remainder is organic matter—decomposing plants and animals. For being such a small portion of dirt, organic matter plays a huge role. It serves as food for microorganisms that do everything from store water to provide nutrients for plants and control pests. Researchers are learning more and more about the exchange between plants and fungi, bacteria and other organisms in the soil, said Robert Myers, a professor of soil sciences at the University of Missouri.

Among other things, soil is a critical stage in the earth’s carbon cycle. Plants draw carbon out of the air, and feed it to the organisms in the soil. In return, they provide nutrients plants need, acting as a natural fertilizer. Disrupting the soil releases all of that carbon back into the atmosphere. As it is exposed to air, the carbon oxidizes, becoming CO2 and a major contribution to climate change

“Some people talk about it as an underground carbon economy,” Myers said.

But the same organisms are also very delicate. They need a variety of plants to feed on and are killed off when exposed to the sun and wind through tillage. Since colonial times, U.S. soil has lost about half its organic matter, said David Montgomery, a professor of geology at the University of Washington who has written three books on soil health. “It’s sort of like draining the natural batteries.”

As scientists have learned more about this nearly invisible ecosystem, the soil microbiome, they’ve begun to realize that promoting the health of those organisms is key to solving a host of problems in agriculture.

“In the last five years, there has been an awakening of the realization of how critical that life in the soil is to our life,’’ said Ron Nichols, a spokesman for USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service. “[It’s] what really enables this whole synthesis process—to be able to cycle carbon from the air into the soil that makes those other nutrients available to plants, that in turn provides us with oxygen and the food that we eat.”

NEW AND IMPROVING testing techniques are increasingly giving scientists and farmers a better look inside the soil and promoting better management practices. In recent years, scientists have learned about key soil transactions like exchanges between plant roots and microorganisms that provide nutrients to the plants, and gotten better at assessing organic matter in the soil. The work is underway in a variety of places—land grant universities are working with USDA and even grower groups and agribusiness companies are looking at and sponsoring some of the work to see how it could be implemented into their farmers’ operations.

Promoting soil health comes down to three basic practices: Make sure the soil is covered with plants at all times, diversify what it grows and don’t disrupt it. What this means in practice is rotating crops, so fields aren’t trying to support the same plant year after year. And it means using techniques like “cover-cropping”–planting a secondary plant like grasses, legumes or vegetables–between rows of crops or on other exposed soil instead of leaving it bare. Using a cover crop protects the soil, reduces erosion, encourages biodiversity and returns nutrients like nitrogen to the earth.

For the most part, agriculture isn’t very good at doing any of these things.

While farmers pride themselves on the stewardship of the land, many have been farming the same way for years, and old habits die hard. Farms have had to get bigger to stay competitive, making it harder for growers to be able to pay attention to the needs of each acre. The majority of farmers in the United States grow the same thing year after year due to a mix of government incentives, habit and ease. Many still till the soil for weed control, albeit considerably less than they have in the past, thanks to herbicide-resistant crops.

“There are a lot of cultural pressures [against] changing in agriculture,” Cobb said, adding that many farmers in his area have questioned what he’s doing. “If you change, you are kind of seen as challenging what's right—and it might be taken that you think everything else is wrong.”

Even organic farms have things to learn from the soil health movement. While organic production at its base is aimed at promoting the productivity of the soil, some farmers do still till to control weeds and use nonchemical fertilizer, such as compost, that can run off the land. There is also no requirement for organic farmers to rotate their crops, use cover crops, or practice holistic soil management, though some do.

The USDA estimates that most U.S. acres planted with major crops—about 60 percent—were still tilled in 2010-2011, the most recent numbers available. Just 2 percent of cropland had cover crops over the same time period.

To the obstacles of farming culture and cost, advocates have another frustration: Washington. The federal crop insurance program is based on farmers planting the same crop in the same place each year to have a record for production, and it is not flexible enough to account for practices like cover crops. That reduces incentives for farmers to try new things, since the government-backed program will pay out whether they adopt good practices or not. And since taxpayers subsidize premiums, an increasing reliance on crop insurance to account for low--performing crops often doesn’t hurt a farmer’s bottom line.

“If we got rid of those subsidies, that would be the quickest way to get people to migrate to healthier soils,” said Dan DeSutter, an Indiana farmer who has been using holistic soil health practices on his land since the early 1990s. “If we are going to be subsidizing crop insurance, we should give the taxpayer something to show for it, which is clean water, clean air and healthy soil.”

Though lawmakers have allocated money for farmers seeking help moving toward holistic soil management, those programs are voluntary. Congress is currently looking at updating the farm bill—the main omnibus vehicle for national agriculture policy—before it expires at the end of September 2018, but in an already tight budget year, and with farmers generally reluctant to follow any new government mandates, it’s unclear if they will have the appetite to require farmers to adopt newer soil-rejuvenation techniques.

Despite the best efforts of soil health advocates, the rate of synthetic fertilizer use is still on the rise. According to USDA, 97 percent of corn acres nationally needed fertilizer in 2010, the most recent numbers available, as opposed to 85 percent in 1964. The amount of nitrogen used per acre skyrocketed in that time period. In 1964, farmers were applying on average 58 pounds of nitrogen per acre. By 2010, the average was 140 pounds. It’s unlikely those numbers have changed much since 2010.

SOIL HEALTH HAS become the agriculture topic du jour around the world. The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization declared 2015 the International Year of Soils, and the Paris climate deal signed in December of that year included a commitment from signatories to increase soil carbon by 0.4 percent each year, even as it left out other agricultural issues. Doing so, proponents argue, could be enough to halt the annual increase of CO2 in the atmosphere, curbing the rate of global warming.

It’s also a water-conservation issue, because healthy soils don’t just produce their own fertilizer, they’re better at absorbing water. The U.N. FAO estimates as much as 40 percent of rainwater runs off uncovered dry land soil. But organic matter can hold up to 90 percent of its weight in water and releases that moisture slowly over time, particularly helpful in areas prone to drought.

Domestically, the Natural Resources Conservation Service is increasingly working with farmers to help them adopt better soil management practices, and providing grants and loans to help them get started. Farm groups are also getting involved. In 2014, the National Corn Growers Association, with help from Monsanto, NRCS, the General Mills Foundation, and others, teamed up with the Environmental Defense Fund and the Nature Conservancy to create the Soil Health Partnership to identify and test soil health practices and pass them on to farmers.

If they make progress, American farms will start to look more like DeSutter’s 4,000-acre farm in west central Indiana. Instead of neat rows stripped of extra foliage, his fields look messy, since each is planted with at least two crops. He rotates his fields among corn, soy, wheat and alfalfa, and between the rows he plants grasses like rye, and legumes like beans and lentils. He’s starting to bring cattle onto the land to improve soil health even further with manure, a natural fertilizer. When he started no-till farming and using cover crops in the early 1990s, his soil had about 1.8 percent organic matter. Now it’s at 4.5 percent and still ticking up.

“It’s a much more complex system,” DeSutter said. Conventional agriculture, on the other hand, is “like following a cookie recipe. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist.”

The payoff for changing that approach is significant, he added, but also requires reckoning with the fact that the land they’re farming, and living on, is a much more complex system. “Instead of playing checkers,” he says, “we are trying to figure out how to play chess.”

Jenny Hopkinson covers agriculture and food policy for POLITICO and POLITICO Pro.

California’s clean-water-for-all experiment begins to deliver.

The state was the first in the U.S. to declare a human right to water.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Hundreds of thousands of California residents, perhaps as many as one million of the 39 million people in the state, do not have safe drinking water or toilet facilities. The wide gap in access to a basic need became a rallying cry more than a decade ago when social justice advocates began promoting a new water strategy for California, a strategy that resulted, in 2012, in a first-of-its-kind state statute that declared safe, clean, affordable water and sanitation a human right.

Lawmakers encounter those principles today as they debate how to fund water system maintenance for poor communities and design the nation’s first state-run water utility bill assistance program.

The right-to-water movement took time to accumulate allies. It persevered through skepticism and a governor’s veto. But then on September 25, 2012, Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB 685, which stated that “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.” The law also asked, but did not require, state agencies to consider that policy in their work. California, a leader in so many environmental laws, was the first state to enact such legislation.

Five years later, what has the law amounted to? Quite a lot, especially during the state’s recent deep drought, which gave the law’s goals a boost. Far from being the symbolic gesture that some assumed it would be, the law has resulted in significant adjustments to state policy and practice.

“There’s been a sea change in how the state thinks about water — which is saying something in a state in which water is highly politicized and low-income communities are on the short end of the stick for access,” said Britton Schwartz, a fellow at the Environmental Law Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley and a long-time advocate for the human right to water.

Circle of Blue interviewed 18 people who have played a role in passing the human right to water legislation and implementing it: lawmakers who introduced bills to extend water access, organizers who built coalitions in support of the law, utility trade groups, people from communities with dirty water, and state officials who are turning the words of the law into actions.

In these conversations, a consensus evaluation emerged. First, the law has, without a doubt, resulted in substantial changes to state water policy. Responsibility for drinking water is now consolidated in a single agency, the State Water Resources Control Board, which, thanks to new legal authority, has added programs and tools for assessing water needs and responding to them. Voter-approved bonds and state budgets have freed up hundreds of millions of dollars for water projects in poor communities. The management process is more inclusive, too. More people have a voice in water decisions, and state regulators and water managers are paying closer attention to the needs of communities on the margin.

“What the law does is more important than mandating water deliveries. It democratizes the decision-making process,” said Mike Eng, a former Assembly member and the sponsor of AB 685. “That’s the enduring worth of the human right to water.”

Second, there is still much work to do. If policy changes and more democratic management have set the playing field, the game itself is just beginning. Sustainable drinking water solutions have been achieved for only a few of the hundreds of thousands in need, and sanitation has largely been ignored. Some of the legal powers the state acquired, including a law requiring stricter oversight of groundwater, a flashpoint for water access in the recent drought, are still too young to have had an effect. There will be tough financial choices ahead for a state that is also prioritizing investments in flood control, dam repairs, water recycling, and water storage.

“The statute is only just now starting to unspool in a way that might affect change,” asserted Mike Antos, senior watershed manager at the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority.

The third consensus view is that the main obstacles to the clean-water-for-all goal are money and preventing rivers and aquifers from being polluted in the first place. Who pays? and How much? are questions of the day in the Legislature, which is debating a bill to fund the operation and maintenance of water systems in poor communities. Funding will also be a point of contention for the state-run water affordability program, which the State Water Board will present to the Legislature by February.

It was a radical idea once, the human right to water. Over the years, the idea has gained slow acceptance in California. In the beginning, though, it did not always seem that such progress would be made.

A History of Neglect

The Salinas Valley, extending inland like a splinter from the central California coast, is an agricultural dynamo, often called America’s salad bowl. It produces more than half of the nation’s broccoli and lettuce along with dozens of other crops. It’s also a region rich in the history of two related social movements — the struggle for farmworker justice and the human right to safe water.

Horacio Amezquita, since he was a teenager, has lived through both. The valley’s farmworker community, mostly immigrants to the land of plenty, had little power and less money when they sought permanent housing after being evicted from a Salinas Valley worker’s camp in the early 1970s following a labor strike.

Kicked out of La Posada trailer park in Salinas, some of the workers fixed their sights on an abandoned camp south of the city set amid the fields in which they toiled. It was a long campaign. Years of negotiating land rights, acquiring the land, fending off opposition from schools and growers, and securing federal development loans culminated in 1979 with the construction of San Jerardo Cooperative, where Amezquita lived for 34 years and is now the general manager.

With 60 homes and four rental units, San Jerardo was the first housing cooperative in California organized by farmworkers, and it laid a legal foundation for five other cooperatives in Monterey County.

Then came the fight for clean water. Not that many years after the homes were built the community’s wells started to turn sour for the roughly 250 residents of San Jerardo. Chemicals and nutrients applied to fields of strawberries and grapes, broccoli and lettuce, cauliflower and cabbage to kill insects and make the berries grow fat had moved downward into groundwater.

In 1990, San Jerardo’s first well tested above state standards for nitrate, a byproduct of plant vitamins that is suffocating for infants. The water also contained 1,2,3-TCP, a fumigant and pesticide. Three years later a second well was spoiled. The third and final well was condemned in 2001, and the residents of San Jerardo started to use bottled water for drinking and cooking.

Poor and cut off from traditional networks of political power, San Jerardo and communities like it dot the map of California. With the human right to water, they sought a voice that had been denied for so long.

If At First You Don’t Succeed…

In the last days of February 2009, an unusual bill appeared in the California Assembly. AB 1242 ordered state agencies “to employ all reasonable means” to secure “clean, affordable, and accessible water” for all human beings. Though Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had clean water clauses in their constitutions, no state had passed a right-to-water law with a scope as wide as what AB 1242 proposed.

Supporters knew that they faced a difficult path, and they were proved correct. Though it cleared the Legislature, the bill did not earn the governor’s endorsement.

On October 12, 2009, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed AB 1242. Schwarzenegger “wholeheartedly” supported the bill’s premise, but signing it into law, he argued, would result in lawsuits rather than water access.

“We should be doing everything we can to ensure that our communities have access to clean, affordable water for our citizens,” Schwarzenegger wrote in his veto message. “But the language of this bill will undoubtedly lead to potentially costly and constant litigation. This moves our limited state resources away from the day to day operations of achieving our clean water goals and puts them in the courtroom.”

Schwarzenegger instead signed two bills that directed state and federal money to poor communities. “Our most pressing barrier in achieving this goal is not desire, it is funding,” he wrote, presaging an argument that continues to this day.

Try, Try Again

Supporters of the bill were not deterred by the failure. In other arenas, in fact, they were making progress. After years of debate, the United Nations General Assembly, on July 28, 2010, passed a resolution that recognized the human right to water. It was a landmark accomplishment for human rights campaigners.

Advocates in California used the UN action to their advantage. They invited the UN’s appointed expert on water and sanitation to witness the state’s shortcomings.

In February and March of 2011, Catarina de Albuquerque, the UN expert, came to the United States to investigate water and sanitation access for the poor and marginalized. In California, she toured Seville, a town in the San Joaquin Valley with groundwater polluted by nitrate. She met with leaders of the Winnemen Wintu tribe, who worried about the destruction of traditional fishing sites and cultural grounds. She visited a homeless camp in Sacramento in which a self-appointed “sanitation technician” hauled the camp’s human waste — between 130 pounds and 230 pounds per week — on his bicycle to a public restroom where he flushed the mess down the toilet.

“It was a real eye-opener for a lot of people at all levels that there is a problem equivalent to what’s going on in third-world countries,” recalled Maria Herrera, then working at the Community Water Center and now at Self-Help Enterprises, a community development organization in the San Joaquin Valley.

That same winter, in February, the human right to water bill was revived in the California Assembly by Mike Eng, a former member of the Monterey Park City Council.

Like the residents of San Jerardo, Eng lived in a community with a contaminated groundwater supply. Perchlorate, an ingredient in rocket fuel, tainted two of Monterey Park’s 11 wells. Arsenic was found in concentrations above state standards in six wells.

A deep but relatively narrow coalition led the campaign. There were social justice groups with an environmental focus such as the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water, Community Water Center, Food and Water Watch, and Clean Water Action. Environmental groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council and Sierra Club took part, too. The Winnemem Wintu tribe was a sponsor. There were also religious groups such as the Unitarian Universalist Services Committee, which was active in the campaign to get the UN to recognize a right to water, and the Catholic Charities Diocese of Stockton.

Britton Schwartz, who worked for the Community Water Center at that point, was one of the organizers on the frontlines and helped to educate elected officials and bureaucrats about the goals of the bill. In 2008 and 2009, she attended county Board of Supervisors meetings, regional water planning meetings, Department of Public Health meetings — any meeting in which water was being discussed. The message, unfamiliar to many in those rooms, that clean drinking water was a legal right turned heads.

“People were looking at me like an alien,” Schwartz recalled.

Campaigners took their message directly to lawmakers, organizing rallies on the Capitol steps. In a parody of the wine industry, they handed out bottles of Central Valley Special Blend, water that was contaminated with arsenic, uranium, bacteria, nitrate, 1,2,3 TCP, and other chemicals. “DO NOT DRINK,” the label read. “100% Community Tap Water.”

De Albuquerque, the UN expert, returned to the state to speak in favor of the bill, which was opposed by large water utilities and farm groups.

Amezquita remembers driving three or four hours to Sacramento to lobby lawmakers. “A lot of organizing took place to fight for the human right to water,” he said.

The law’s passage was also a result of the maturation of the environmental movement in California, a “coming of age,” in the words of Colin Bailey, now the executive director of the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water. By 2012, people who started as organizers had moved into positions of power, he said.

Martha Guzman Aceves, for instance. Formerly a legislative coordinator for United Farm Workers and a co-founder of the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water, Guzman Aceves was named Gov. Brown’s deputy legislative affairs secretary in 2011. She was responsible for environmental and natural resources bills and the human right to water law was in her portfolio.

The bill supporters made a strategic move, Guzman Aceves said, when they changed the language of AB 685 to remove any hint of legal obligation on the part of the state or utilities. That modification sidestepped the core question and rallying point for opposition to the human right to water, which is how do you deliver?

“For someone to say you have a right to water means that someone else is required to give it,” said Doug LaMalfa, then a state senator and now a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, during the floor debate in the Senate. LaMalfa voted no.

Unlike the attempt three years earlier, Eng and supporters took a different tack. Instead of mandating any specific action on the part of utilities or state agencies, the bill advanced a “moral policy statement,” explained Guzman Aceves, who now holds a seat on the California Public Utilities Commission.

“Once we have a common baseline, we can build off it,” she said. “And that’s what happened.”

The amended language was enough to push the bill across the finish line. Gov. Brown signed the bill into law on September 25, 2012.

It was a euphoric moment for the campaigners. But they were also aware of the challenges still to come.

“Today we’re celebrating this great victory, but tomorrow means implementation,” said Susana De Anda, co-founder of the Community Water Center, in October 2012. “Tomorrow means really ensuring that safe drinking water comes out of people’s taps. We recognize that justice might take a long time but we’re committed to the end.”

California towns tackle nitrate pollution with local solutions.

It will take decades to slow nitrate contamination in groundwater from industrial agriculture in parts of the state of California, so communities are taking matters into their own hands to get clean drinking water.

PORTERVILLE, CALIFORNIA, A town of about 50,000 people, lies nestled at the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, near the gateways to Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. It’s an idyllic setting, but in the nearby rural communities of East Porterville, Poplar, Terra Bella and Ducor, many residents get their drinking water from private wells that are rarely tested for contaminants. That’s potentially dangerous because groundwater in the area is known to be polluted with nitrates.

A program in Porterville is trying a new tactic to help people in these communities obtain clean water. It’s one of a number of local responses trying to tackle the state’s nitrate problem.

A by-product of the nitrogen fertilizer that farmers put on crops, nitrates in groundwater have increased since the rise of industrial agriculture in the 1950s. Growers apply more fertilizer than the crops can absorb, and the excess nitrates are then washed into surface or groundwater when the crops are irrigated. In California, the most heavily affected areas are the Tulare Lake Basin in the San Joaquin Valley, where Porterville lies, and the Salinas Valley on the Central Coast, 100 miles south of San Francisco. Although nitrate pollution can also come from animal waste and ineffective sewage treatment, in these areas 96 percent is from crop agriculture, according to a study conducted by the University of California, Davis for the State Water Resources Control Board.

It’s difficult to know exactly how many people are exposed to nitrate-laced drinking water across the state. The U.C. Davis study estimated that up to 250,000 people using 10,000 private or small local system wells are at high risk of excessive exposure to nitrates in the San Joaquin and Salinas valleys. And recent state data identifies about 60 public water systems chronically out of compliance with safe nitrate levels.

The biggest known health risk to consuming nitrates is blue-baby syndrome, or methemoglobinemia. When babies consume nitrates, bacteria in their stomachs convert it to a more toxic form, nitrites, which reduces the body’s ability to deliver oxygen. Symptoms include difficulty breathing and a bluish color around the eyes and mouth. Without medical attention, the condition can induce coma and lead to death. Pregnant women are also at risk. Some studies have shown links to birth defects and certain cancers, but the evidence is not as clear.

So what’s California doing about it?

The state started to get serious about cleaning up nitrates a decade ago. It is now working with growers to stop new pollution and is considering how it might clean up old contamination. But it’s costly to clean an entire aquifer, and even extraordinary efforts would take several decades to pay off.

So the state is also focused on funding interim local solutions to supply people with safe drinking water. Most of these instant fixes include bottled water, installing a filter at the kitchen sink or a big filter at a wellhead. Other, more permanent solutions include drilling a new well or connecting contaminated systems to cleaner ones in neighboring towns. In the meantime, towns are pursuing their own solutions.

Rural Outreach

Cristobal Chavez, a former truck driver and Teamster, lives with his wife and five foster children outside the small Tulare County town of Poplar, where he has 15 acres and raises sheep, goats and chickens.

High levels of nitrates were reported by municipal water systems in his area, prompting the nonprofit Community Water Center based in nearby Visalia to ask to test Chavez’s well two years ago as part of an outreach campaign to private well owners. The state doesn’t require private well owners to test their wells for contaminants, and many people don’t know that they should or they can’t afford to do so.

Results for Chavez’s well showed levels of nitrate more than three times the maximum contaminant level allowed by law, according to the Community Water Center.

“We were surprised. We were using that water for drinking and everything,” says Chavez. “Since they told us, we don’t do it anymore.” But that’s been at a cost of nearly $200 a month for bottled water.

Chavez’s well went dry three years ago during the drought, forcing him to dig a deeper well. Now he says, “I have plenty of water, but I can’t drink it.”

Without access to a community water system, many private well owners are on their own when it comes to finding solutions to nitrate contamination. But in Porterville, about 10 miles down the road from Chavez, Self-Help Enterprises, a local nonprofit, is working to change that.

In an area where many residents are low-income and rely on private wells, Self-Help Enterprises decided to target those most affected by nitrates: expectant mothers and infants. The organization offers them water tests when they visit the office of their local Women, Infants and Children (WIC), a federal food and nutrition program. A grant from the Central Valley Salinity Coalition, a nonprofit alliance of agricultural businesses and water districts working to clean up salts and nitrates, has funded a six-month pilot program that launched in April.

So far, 63 people have taken home testing kits, and 25 have returned them, says Abigail Solis, community development specialist with Self-Help Enterprises. Of the 25 water samples tested, eight had nitrate levels above the legal limit and one was four times the legal limit, she says.

If a test reveals dangerous nitrate levels, project funds will cover bottled water delivery as long as the pilot runs – through to October of this year – or an under-sink filter, which cleans the water through reverse osmosis.

As for why more people aren’t taking advantage of the program, Solis says access is likely an issue. The WIC office can accept water samples only between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m., Monday through Wednesday, to ensure that the sample is tested quickly enough to gives accurate results. People are at work during the day, says Solis, and transportation is a hurdle for many. Solis is working to obtain funding to continue the project and hopes to send someone out to collect samples from people’s homes to increase participation.

“Sometimes we think families either don’t care about these issues or they’re not aware,” says Solis. “We have learned families are very aware and care very much. They’re just not sure what they can do about it.”

Bottled Water Reliance

Irma Medellin started the grassroots organization El Quinto Sol de America to drive civic participation in Tulare County communities where many residents don’t feel they have a political voice, she says. A big part of that work has included raising awareness about water contamination.

“It’s necessary to work together so our government listens and then the government can also include us in their plans,” she says through a translator. “The government has a lot of money, but poor communities are often the last in line.”

Grassroots activism in the valley in recent years has helped to bring more resources to hard-hit areas. The state now has 85 active projects supplying bottled water to California communities suffering from water contamination or drought impacts. Thirty of those projects address nitrate contamination.

“The agricultural industry is contaminating the water, and we pay the price,” says Medellin.

But in at least one area of the state – the Salinas Valley in Monterey County – some farmers are finally paying too. In that area, both growers and residents rely primarily on groundwater, which, thanks to decades of intensive agriculture, is polluted with nitrates. Starting this summer, individuals using private wells and towns affected by nitrate pollution are now receiving bottled water deliveries paid for by local area growers. This temporary program emerged after the State Water Resources Control Board and the local Central Coast Regional Water Control Board made moves toward cracking down on agricultural polluters in the area.

They drafted an enforcement order against the larger farmers in the Salinas Valley, prompting the parties to agree to a settlement in which growers would provide affected people with clean water immediately and work to install long-term water supply solutions, such as digging deeper wells for them or connecting them to nearby water systems.

Technological Solutions

Bottled water programs are only a stopgap measure until more permanent solutions can be found, but that often takes years. Another option is point-of-use filtration systems that go under a sink and use either reverse osmosis or distillation, but they usually cost several hundred dollars apiece and most households would need several. Filters also need to be changed regularly.

Pending state legislation, Assembly Bill 166 would direct the State Water Resources Control Board to study the feasibility of providing rebates for household water filtration systems for residents.

Large water filtration systems can also be installed at the wellhead. Typically those systems have been considered expensive, slow and challenging because they require ongoing maintenance, such as changing filters and properly disposing of the brine waste that is generated.

But a United Kingdom-based company, Ionex SG, thinks it has found a better way. Its system uses ion exchange, a technology that’s been around for years and exchanges a contaminant with a more desirable substance, says chief executive officer Phil Chandler. Traditional ion exchange systems generate large volumes of waste, but Ionex’s technology reduces that waste, he says, and thus lowers the disposal costs.

The technology – which can be used to treat contaminants such as nitrates, as well as hexavalent chromium, uranium or perchlorate – is already being tested in California with four different water agencies.

“After five years of self-funded research and field trials [Ionex SG] is conditionally approved for drinking water applications in California,” says Chandler. And since 2015, the company has been treating nitrate-contaminated drinking water in the San Joaquin Valley for Triple R Mutual Water, which has 152 connections in the Sierra foothills town of Springville in Tulare County.

Chandler says that Ionex is committed to working in the San Joaquin Valley, where the region’s small, rural communities provide a good opportunity to test the company’s technology. “I can predict that we will be installing further treatment systems in the region in 2018.”

Making New Connections

Treatment systems to remove nitrate aren’t the only option for impacted communities. Seville, a small, rural town nestled among orange groves in the eastern San Joaquin Valley, is populated with second- and third-generation agricultural workers, as well as recent immigrants. The community of about 500 has just one well, and it’s tainted with nitrates.

Ruben Becerra grew up in Seville and now lives in a neighboring town, but he returns to his boyhood home several times a week to deliver bottled water to his 93-year-old mother. “The water is not drinkable,” says Becerra. In addition to nitrates, the leaky infrastructure also invites bacterial contamination. Buying bottled water has been an economic hardship for local residents, many of whom are elderly, disabled or work in low-income jobs, he notes.

Becky Quintana, also from Seville, has been drinking and cooking with bottled water for nearly a decade. But some of her fellow residents couldn’t afford $60 a month for bottled water. “They’d only buy water for infants, and the rest of family would drink the tainted water,” she says.

“For years Seville was a stepchild out in the country – totally abandoned out there,” Becerra says. “No one wanted to deal with us. But officials now are forced to work on the problems.”

Things improved three years ago when the state agreed to supply everyone with bottled water. But the residents of Seville are also pursuing more permanent solutions.

Seville joined forces with its neighboring town of Yettem to dig another well, where they found clean water. Now they must expand the well and build pipes to both towns, says Ryan Jensen, community water solutions manager at the Community Water Center.

However, just because the water is clean now doesn’t mean it will stay clean. “The well could become contaminated,” says Jensen. “Then they would have to shut it down and drill a new well.” Or now that the new combined Yettem-Seville water district will have three wells, managers could blend contaminated water with less contaminated water to meet federal water-quality standards.

Another possibility is to obtain water from a surface water source, and a multi-town partnership, including Seville, is exploring that possibility.

“This has been a marathon for us,” says Quintana. “I’m not sure how many months or years it will be till we get clean water coming through our infrastructure.”

Breakthrough on nitrogen generation by researchers to impact climate-change research.

A research collaboration between the University of Alberta and the University of Vienna has yielded a discovery that could significantly impact climate-change research, said a professor of biology in Edmonton.

A research collaboration between the University of Alberta and the University of Vienna has yielded a discovery that could significantly impact climate-change research, said a professor of biology in Edmonton.

Currently the world’s nitrogen cycle is unbalanced because humans are now responsible for adding more fixed nitrogen through ammonium to the environment than natural sources, said researcher Lisa Stein of the University of Alberta. Excess ammonium has implications on the climate and environment, from dead zones in oceans to a greenhouse gas effect 300 times that of carbon dioxide on a molecule to molecule basis.

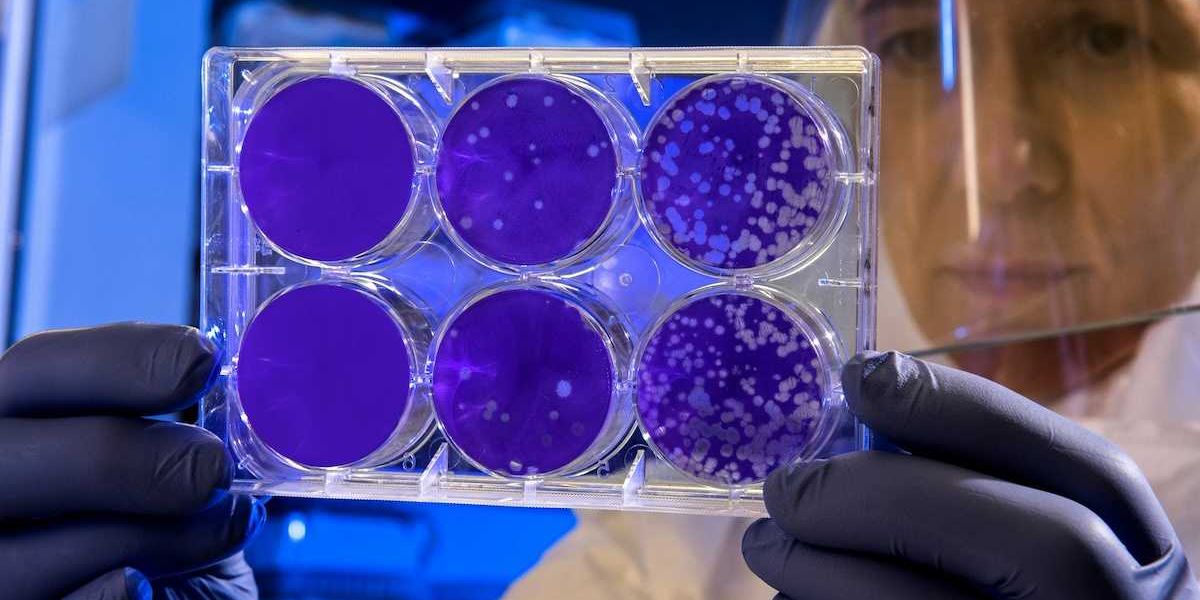

Stein and Dimitri Kits, a University of Alberta PhD grad now working at the University of Vienna, identified and characterized the ammonia-oxidizing microbe Nitrospira inopinata.

Stein said this bacteria is important because oxidizing the ammonium previously was a process done partway by two different microbes. Nitrospira inopinata oxidizes ammonium all the way to nitrate.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to demonstrate that it can with a single source,” she said. “If we can find a way to replace bad microbes with this one, it can help mitigate the problem.”

The process of making fertilizer, known as the Hager-Bosch process, adds massive quantities of fixed nitrogen to the environment. Stein also said the over-application of fertilizer causes a problem.

“Up to 95 per cent of applied fertilizer isn’t delivered to the plant,” she said. Instead microbes start chewing on the fertilizer and release nitrous oxide into the environment. The new discovery could help mitigate this problem.

“The high efficiency of (Nitrospira inopinata) means it is likely producing less nitrous oxide,” she said.

There is still further research to be done, said Kits, who was the lead author on the paper, which was published in the scientific journal Nature.

“So far in this paper we’ve just isolated (Nitrospira inopinata) and characterized some of its basic physiology,” he said.

“The next step is going to be to measure the actual quantities of nitrous oxide that it makes (and) how it might influence the nitrogen cycle where it’s found.”

Stein said this will be done by getting together funding and researchers to measure how much nitrous oxide is produced under various conditions.

But Stein added problems with the Earth’s nitrogen cycle is not something humans can engineer themselves out of.

She said remedying the problem will involve changing behaviours, such as overfertilization in the agricultural industry.

“You can’t just change the microbes and expect the Earth to be all right, you have to stop the feeding.”

rcsernyik@postmedia.com

Uncertainty over water source for Tesla and corporate giants in Reno.

No one seems to know how much water a massive desert industrial complex will ultimately require. But treated urban wastewater may help protect the imperiled Truckee River as more big companies move in.

UST 12 MILES east of Reno, Nevada, across a swath of brown and barren desert hills, some of the largest corporations in the U.S. are forming a new metropolis. Behemoths of manufacturing, retailing and computing are rushing to build new warehouses, data centers and factories at an industrial complex billed as the largest in the world.

The Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, or TRIC, sprawls across 107,000 acres of Storey County, a wedge of desert mountains and plains just east of the Reno metropolitan area. Tesla, Google, Ebay and Wal-Mart are some of the corporate luminaries that have bought in, with 11 million sq ft of pancake-flat industrial buildings already occupied. That’s not even half the total that will eventually be built here.

It’s a modern-day land rush that begs an important question: Where will all the water come from to serve these corporate ambitions?

Surprisingly, no one knows yet. Even the founders of the complex don’t know how much water their powerful tenants will eventually require.

“I don’t have any estimate on water needs from any of the companies at this point,” said Lance Gilman, TRIC’s director, who is also an elected Storey County commissioner. “You gotta set the crystal ball on the table and take your best guess and go for it.”

Tesla, the wunderkind electric-car builder, began producing lithium-ion batteries this year at its Gigafactory on the site, which the company calls the “biggest building in the world.” In just three years the factory has grown to 1.9 million sq ft and may eventually reach 10 million.

Yet Tesla has never revealed how much water its Gigafactory might need. And Nevada officials apparently never bothered to ask, despite twisting arms for months to assemble a $1.4 billion incentive package that lured Tesla to the state.

“I’ve never heard a firm number,” said Jason King, Nevada’s state engineer, whose job is to oversee all water rights in the state.

TRIC is serving tenants from groundwater wells. An extensive on-site water recycling system stretches this supply. It also holds water rights in the Truckee River, which flows adjacent to the complex. But those rights are restricted during drought conditions, which are becoming increasingly common. Gilman acknowledges a more reliable long-term water supply is needed.

In recent weeks, a solution has emerged: Reno and Sparks have agreed to transfer 4,000 acre-feet per year of treated urban wastewater to the industrial complex. This wastewater is currently discharged from the regional sewage treatment plant into the Truckee River, sometimes with undesirable effects on water quality because the effluent is heavy with nitrates, said Reno City councilman David Bobzien.

In return, TRIC and the state of Nevada would relinquish an equivalent amount of Truckee River water rights. This could result in a net water quality benefit because the river water – left instream – would replace treated wastewater now discharged to the river.

The price TRIC will pay for the wastewater has yet to be determined.

Bobzien said the agreement is a positive development for the region, because it ensures the industrial center can continue growing without impacting the Truckee River. He also said the deal has come a long way from the first proposal offered by TRIC and its tenants, which “wasn’t well received” by many in local government.

“The initial proposal was, ‘Hey, you guys pay for some infrastructure, build us a pipeline, and we’ll take all the wastewater off your hands.’ As if it was going to be this wonderful thing for us,” Bobzien said. “Overall, the concept is in a much better place now.”

Most of the water that serves the Reno-Sparks metro area comes from the Truckee River. This ribbon of Sierra Nevada snowmelt begins at Lake Tahoe and ends at Pyramid Lake, a vast saline oasis in the desert belonging to the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe.

The tribe and numerous agencies have been working for decades to restore rare fish to the lake and the river that feeds it, including Pyramid Lake Cui-ui and Lahontan cutthroat trout. And for 90 years, a federal watermaster has overseen the river to make sure every drop is used wisely.

As a result, new demands on the Truckee River are viewed with broad concern, including TRIC’s 4,000 acre-feet of instream water rights.

“Ever since European settlement, we’ve been using and abusing that river,” said Mickey Hazelwood, Truckee River project manager for the Nature Conservancy, which has led an ambitious restoration effort on the river for 15 years. “What buildout will look like for that industrial center, nobody really knows.”

The deal to share treated wastewater could alleviate these concerns.

The draft agreement would give TRIC access to 4,000 acre-feet of treated wastewater annually for 30 years, with two 20-year extensions available. TRIC will have to spend about $35 million building a 10-mile pipeline to access the wastewater, plus another $30 million for onsite improvements to manage and distribute the water to its tenants.

Gilman said the effort is worth it, because a reclaimed wastewater supply would be “absolutely secure.”

“We do know there will be a significant need for the reclaimed water,” he said. “It’s as secure as you can get, because we’re taking it out of a resource stream that’s coming from all the development in the Reno-Sparks market area.”

Tesla is the star tenant at TRIC – and the biggest tenant. It also is certainly one of the largest water users.

Jason King, the state engineer, said he heard “very early in the process” of luring Tesla to Nevada that the company could require as much as 2,500 acre-feet of water per year for its battery manufacturing at TRIC. If true, that’s almost half the total annual groundwater supply at the complex (5,400 acre-feet, according to Gilman) being absorbed by a single tenant.

“It wasn’t clear to me at the time whether that’s once the Gigafactory is up and running, or whether it includes construction water,” King said.

Tesla officials declined to comment.

The Reno City Council is set to review the wastewater deal at its meeting Aug. 23, followed by the Sparks City Council in September. The two cities jointly operate the regional sewage treatment plant that produces the wastewater supply.

There are many details yet to be revealed. One of the most important concerns is the swap of treated wastewater for Truckee River water rights.

Although the wastewater sometimes exceeds nitrate limits allowed in the river, Bobzien said, it still represents an important component of overall Truckee River flows in such an arid environment.

The treated wastewater flow helps sustain fisheries. It also helps sustain water elevations in Pyramid Lake, which has been shrinking for decades as urbanization taps into the Sierra snowmelt that would otherwise reach the lake.

So if 4,000 acre-feet of treated wastewater is pulled out of the river, will the traded water rights replace that in equal measure? That remains to be seen.

Gilman, for instance, said the Truckee River water rights TRIC is contributing to the deal are not currently being tapped. Which means this water is already in the river, and will not replace the diverted wastewater.

“We’re actually not replacing water, we’re leaving what we could be taking in the river,” Gilman said.

For reasons like that, the Paiute Tribe remains skeptical of the deal. The tribe depends on Truckee River flows to sustain Pyramid Lake, the last remnant of a vast inland water body that has been sacred to its people for millennia.

“The main concern is that the river remain whole,” said Donna Noel, the tribe’s natural resources director. “We haven’t seen any details so far.”

The Nature Conservancy also remains wary of the agreement until more information emerges, said Hazelwood. The nonprofit has invested $27 million in Truckee River restoration projects over the past 15 years, including some immediately adjacent to the TRIC site.

“The folks at the industrial center have been good neighbors to our restoration work,” he said. “I wish we knew enough to know where we as an organization stand on this.”

One thing the negotiations have already achieved is enlightening Reno and Sparks to the potential of their treated sewage effluent. Bobzien said it could be decades until area residents are ready to consider recycling that effluent to use as a drinking water resource, as other communities have done. But it now seems like a possibility, at least.

“I think many in local government quickly realized the wastewater effluent – while it is a problem and a liability to us in terms of our discharge requirements – also has a value,” he said.

Brittany′s algae invasion pits farmers against beach lovers.

A plague of algae is washing up on beaches in Brittany. Experts say only a drastic cut in nitrate fertilizer use will get rid of it, but farmers are reluctant to ditch the chemicals.

Vincent Petit was walking his horse along a beach at Saint-Michel-en-Grève in northern France, when the pair suddenly sank into and found themselves stuck fast.

"It was impossible to get out of there and within 10 seconds, my horse had passed out," Petit recalls.

He says he just had time to call for help before fainting himself.

Luckily, that day eight years ago, a man was working to clear the beach of green algae just a few meters away. He rescued Petit. The horse died from poisonous hydrogen sulphide gas released by the rotting algae.

Since then, two people and a few wild boar are believed to have died from the gas, although the government has never officially recognized this.

"It's incredible," Petit told DW. "You wouldn't expect to be exposed to such danger on a beach in France."

A global problem

Yet it's a danger that's becoming increasingly common around the world. Algae of various kinds thrive on nitrates used in fertilizers that run off agricultural land and end up in rivers, lakes and coastal waters.

The worst outbreaks have been seen in parts of the world where agriculture is particularly intensive - including North America, Europe and parts of Asia.

Florida's Lake Okeechobee has become seriously infected with algae, as have coastal waters off the state of Georgia. Parts of the Gulf of Mexico have been labelled "dead zones" because of huge expanses of the blooms which suck up all oxygen.

Last year, algae was blamed for the deaths of 23 million salmon in Chile, and this week tourists were warned to keep out of the water at beaches on the Canary Islands because of dangerous "sea sawdust" algae.

In Brittany, famous for its picturesque rocky coves, green algae is present at eight beaches. All are in small bays where the water doesn't flow away easily.

Green algae are not toxic per se. But when they occur in large amounts and cannot be cleaned away fast enough, they start to rot. Bacteria decompose them and release hydrogen sulphide in the process, a toxic gas smelling of rotten eggs.

Agriculture versus the environment

Farming is one of Brittany's biggest industries, and the region's struggle to tackle the algae is indicative of the competing interests of the agricultural sector and surrounding environment.

Laurent Guernion keeps about a hundred cows near the coastal town of Saint-Brieuc, and grows corn to feed them. He says the chemicals are crucial for farmers to stay competitive.

"If we don't use fertilizer, we won't be able to produce enough food for our animals," he told DW.

"We would have to buy fodder and that would bring down our revenue even further. We are already struggling - the milk price has gone down from 300 to 250 euros per ton over the past two years."

Guernion says he calculates exactly how much fertilizer his crops need, so none ends up in natural waters. But the corn stops growing in August - and no longer soaks up the nitrates in the soil, which are then washed into the rivers and the sea.

Cutting down on fertilizers

Still, Guernion is trying to reduce the amount of fertilizer he uses and the proportion of corn he feeds his cows. He is among the 80 percent of Brittany farmers who have signed up to the region's anti-algae plan.

The government has spent 40 million euros ($47 million) over the past five years trying to combat the problem, and compensating farmers for reduced productivity.

That sum will now be topped up with another 55 million euros, says Thierry Burlot, the regional government's vice-president in charge of environmental matters.

"We will reduce the proportion of nitrates in the water even further," Burlot says. "We will continue to reshape the land so that the water can flow off more easily. Brittany is on the move - we are adapting our agricultural model."

The first anti-algae plan has had some success. Brittany's water quality has improved, with its average nitrate content falling from 50 to 30 milligrams per liter.

But scientists say to eradicate the algae, that figure needs to drop below 10 milligrams.

This spring saw more algal blooms than for the past 15 years, after relatively high temperatures followed a mild winter with few storms to clear the water of nitrates.

And scientists fear weather like this could become increasingly common as a result of global warming.

Rethinking farming

Yves-Marie Le Lay, vice-president of the "Stop the Green Tides" association was born in Brittany and wants his children and grandchildren to grow up on clean beaches.

He believes this will only be possible with a radical switch to less intensive farming.

"We need to thoroughly overhaul Brittany's agricultural model," he told DW, while measuring gas levels at one beach - something he's been doing for the last seven years to flag up the problem.

Le Lay insists this wouldn't be a death knell for the local farming sector.

"Farmers should focus on quality and not quantity," he says. "They would then need less fertilizer. And they wouldn't even lose money, as organic products fetch considerably higher prices.”

But farmers like Guernion say such a strategy is just too risky.

"The prices for organic products are subject to fluctuations on the world markets - just like for conventional products," he says. "We would have no guarantee we could make a living if we produced less, even with higher quality."

So far, the government's anti-algae initiatives have all been voluntary. Which means unless farmers are enthusiastic about going organic, the algae are probably here to stay.