Offshore platforms can vary greatly in size—some are as big as multi-storied buildings, while others resemble small but very tall rooms. The boat carrying Yacovitch and her team also housed a variety of science equipment: methane isotope readers, spectrometers, and other tools to measure methane levels in the air around these sites.

Yacovitch, an instrument scientist at Aerodyne Research, is trying to understand the scope of what some scientists say is a massive environmental issue lurking below our seas. Wells are routinely drilled into the sea floor for oil and gas production, and abandoned when they stop being economically viable—sometimes this is after years of oil or gas extraction, sometimes it's part way through drilling before the well is even finished. But not all of these wells are plugged and properly maintained before being left behind. The result: methane and other gases leaking in unknown quantities for years on end from tens of thousands of holes in the ocean floor.

The harms for the ocean and its inhabitants, and the atmosphere above, are largely unknown. But we do know that methane is about 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas, measured over a 20-year period, according to the

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

An EHN analysis of federal data on oil and natural gas wells found there are 55,315 offshore in U.S. federal waters, 53,724 (97 percent) of which are in the Gulf of Mexico, according to

data from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), as of November 30, 2020.

Of those wells, 28,232, or 52.6 percent, are permanently abandoned or decommissioned. 3,444, or 6.4 percent are temporarily abandoned. And those are only in the U.S., and in federal waters alone. Individual state governments tally and record the offshore wells located in their own waters—and that data is kept separate.

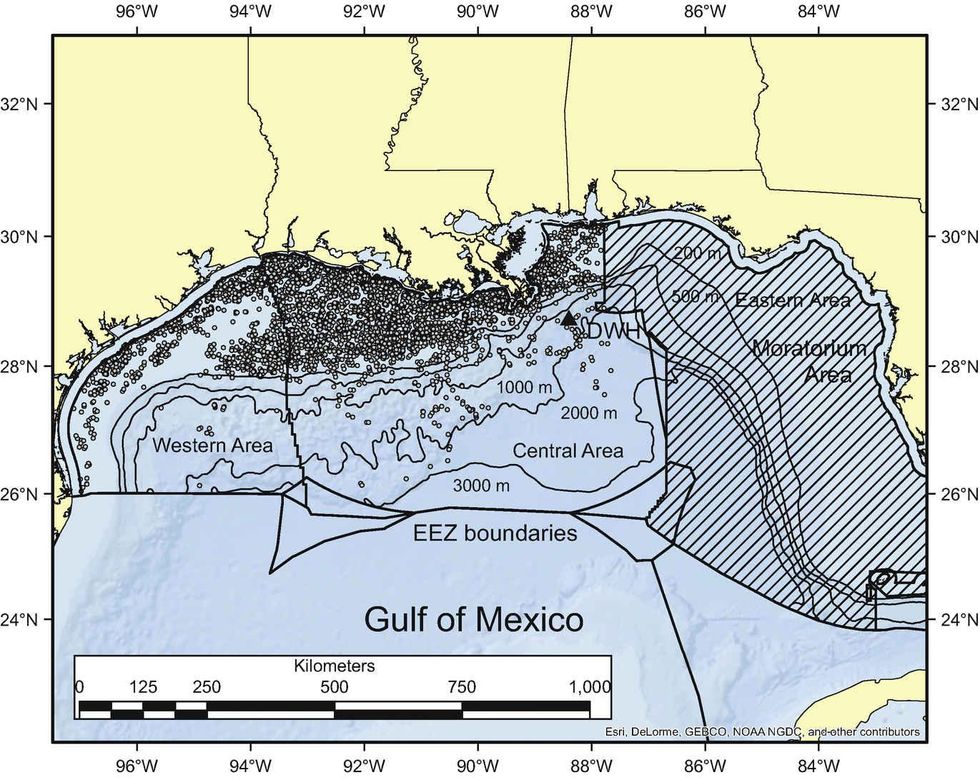

Locations of existing oil and gas infrastructure in U.S. Gulf of Mexico territory, 2017. (Credit: Deepwater Oil and Gas Production in the Gulf of Mexico and Related Global Trends)

Research in other offshore environments from the North Sea in Europe to the Bohai Sea in China indicate a global trend, but EHN focused on the Gulf of Mexico, since that is where the majority of oil and gas drilling occurs in the U.S., and subsequently where the majority of data and research has been collected.

While active oil and gas wells can also be prone to leakage, leaks from decommissioned and abandoned wells are more pernicious. Though all wells are supposed to be plugged before they are abandoned and decommissioned, the state of those plugs post-abandonment is not monitored. Abandoned wells number in the tens of thousands, with abandonment rates increasing yearly.

A well could be active for years, even decades, but an abandoned well that has not been properly plugged could leak methane and other harmful gases in perpetuity. Beyond methane, benzene, nitrogen oxides, carbon dioxide and more all have all been detected in oil and gas well emissions.

Experts say federal oversight and regulation remain inadequate, allowing industry to continually add to the well count without properly documenting crucial site details. Records on the locations, longevity, and emission volumes for wells are incomplete, but emissions from these sites undoubtedly impact ocean ecology—and some of this methane inevitably gets released into the atmosphere.

Regulatory holes

Offshore oil and gas production in the U.S. began in the early 20th century, with production in the Gulf of Mexico beginning in the late 1930s. It was not until 1982, however, that the government created the Minerals Management Service (MMS) and passed the Federal Oil & Gas Royalty Management Act, requiring recordkeeping for where and when wells were drilled, and to whom they were sold.

In 2010, MMS split into what would become BOEM, BSEE, and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue. All U.S. federal waters are now leased out by BOEM, and all wells and platforms are monitored and regulated by BSEE.

Once leases are finalized, companies can drill exploration wells—the initial boreholes used to determine whether an area will be profitable.

And what that exploratory well looks like depends on the geology of where you're drilling. "In offshore environments it can be thousands, maybe even 20,000 or 30,000 feet underwater. And how far into the ocean floor you drill will again just depend on that geology," Wesley Williams, an engineer at Louisiana State University, told EHN

In the early days, companies drilled exploration wells with little to no concern, Williams said—"there's some areas where we joke that it's like Swiss cheese." But now, regulators are more scrupulous.

As they drill, whether exploratory or not, companies consistently check for economic viability, Williams said. When that economic viability tips over to red, the owners either sell or decommission.

But what is considered "economically viable" differs from company to company. Leases and rights to drill at one site may pass through multiple companies over the years. Once a well stops generating interest or profit potential, it is decommissioned.

Every well is supposed to be decommissioned when no longer active in concordance with federal law. Platforms at the surface are supposed to be removed, and boreholes in the ocean floor need to be plugged with cement or a similar material. But not every well is decommissioned properly. Sometimes, especially if the parent company goes out of business, they are simply orphaned, left to idle and leak until the government handles plugging.

Erik Milito, president of National Ocean Industries Association wrote EHN in an email: "Between Federal plugging and abandonment regulations, which require the installation and testing of barriers, and the natural tendencies of methane, the likelihood of methane emissions escaping from oil and gas activities on the sea floor is extremely low."

Sandy Day, BSEE's press secretary wrote EHN in an email that "BSEE inspects all offshore facilities at least once per year; and inspects drilling rigs at least once per month. BSEE conducts pollution surveillance and offshore site-specific inspections using helicopters flying from district office locations around the Outer Continental Shelf." Day did not address how they monitor abandoned or orphaned wells, specifically.

But federal policies for these wells are "difficult to administer and it's easy to evade," Megan Milliken Biven, an energy policy researcher and former BOEM employee, told EHN. And these agencies' policies are basically all "beyond the scope and capability of the resources the agency has."

She added that most of these agencies' "due diligence" safety evaluations are more about giving themselves a pass than actually discerning risk. BOEM has a guidebook to evaluate the environmental impact of any drilling operation, "and I would say that that document doesn't exist to actually remove or mitigate any kind of risk. It's only to state the risk so that when someone tries to sue the agency, they can say, 'look, we looked at the risk.'"

Milliken Biven also said that it's hard to define what holes there are in the system, because "that assumes that there is a standard for plugging and abandonment, that assumes that there is a standard for checking for leaks, that assumes that there is a standard for site clearance and restoration...but there is none."

“Super-emitters” and the undocumented

The Global Methane Initiative, an international effort to reduce methane emissions, estimates about 20 percent of human-caused methane emissions come from the oil and gas sector. That's likely an underestimated figure, Yacovitch told EHN, "because there's really not that much data on offshore assets—the field of measuring emissions, particularly in the Gulf of Mexico, is fairly new."

Yacovitch and her team randomly selected and studied 103 sites, looking at air quality from the platforms as seepage on the ocean floor is hard to measure. The team looked at a mix of both active and decommissioned, shallow and deep, and found platforms emitted methane at widely ranging rates: from zero to 190 kilograms per hour. And the top 2 percent of emitters accounted for 20 percent of the total methane emissions.

The data show that not every well, orphaned or not, is guaranteed to leak. But when a well does leak, there is huge variability in emissions.

Drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico. (Credit: Tara Yacovitch/Scott Herndon)

They only surveyed 103 areas—so there is a chance that, though they randomly selected their surveyed regions, their data may not be an accurate representation.

Nonetheless, the study points to an incredible problem. The top 2 percent of emitters, so-called super-emitters, leak very high levels of methane, but are largely unidentified in a literal sea of sites. While 2 percent may sound small, when the total is 55,292 wells in federal waters, that amounts to 1,104 super-emitters in national waters.

What's more, "a lot of wells are undocumented," Mary Kang, an environmental engineer at McGill University, told EHN. Kang has years of research experience looking at leaky, abandoned oil and gas wells. "You go out and you don't find them. And then you go somewhere else looking for one, but you find 10 others."

An Environmental Science & Technology paper from earlier this year states that "current U.S. government inventories overestimate the number of oil and gas platforms in federal waters while missing platforms located in state waters." Scientists found that more than 1,300 offshore facilities were missing from government documentation.

These facilities are likely older and therefore larger, with disproportionately high spikes of methane emissions, from early industry years when tracking measures were even less stringent.

The authors suggest that U.S. methane emissions for the country's whole natural gas supply chain are as much as 60 percent greater than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

Energy companies working in the Gulf of Mexico produce about 1.7 million barrels of crude oil per day. (Credit: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement)

Individual states are responsible for sites in their own waters, but as far as monitoring and tracking their wells, "different states definitely do it differently, and some do it almost not at all," Chris Konek told EHN. Konek manages the oil and gas methane science studies at the Climate & Clean Air Coalition (CCAC), which is part of the UN Environment Programme. He said identifying where wells are in the vast ocean is a difficult undertaking.

Yacovitch and her team experienced that challenge. When trying to navigate to survey sites, the team found discrepancies between where government records said oil and gas platforms were versus where they are. "Sometimes we would say, 'We swear there's a platform out here,' but we'd go and there's nothing there," Yacovitch said.

A lot of research in this area thus far has focused on measuring how much methane each well is emitting, said Kang, who has spent years researching abandoned oil and gas wells. But, terms like "leakage" are poorly defined.

"If you see no methane emissions on the ocean floor, or at the water's surface, does that mean there was no leakage? No, it doesn't," Kang said. An absence of gas bubbles coming up to the ocean's surface and low methane measurements in the air do not guarantee there is zero gas escaping.

Kang also said there is no standard definition for what flow rate constitutes leakage across the industry. If you look at just high emitters, depending on how you define "high," then leaky wells are just 10 to 20 percent. But depending on how you define that threshold for leakage, the proportion of leaky wells could go up to 50, maybe 80 percent. "The bigger questions are, how many wells are out there, and how long are they emitting for?" Kang added.

There are many wells that are active for just a few years, if at all, but once a well is abandoned, "they're going to be abandoned for decades and centuries," Kang said.

Industry reports show pretty consistent numbers of newly drilled or active wells in a given area of oil and gas production over time. But if you read between the lines, that means that the numbers of abandoned and decommissioned wells are always growing.

“A multi-billion dollar issue”

There is an upcoming wave of wells that will be plugged and abandoned in the coming years—a surge that science and industry have long seen coming. According to a June article in World Oil, "In the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, which generates about 15 percent of the nation's output, explorers are expected to spend about $1 billion a year over the next half decade to decommission hundreds of wells."

A 2018 paper says that "in recent years, the shallow water region has witnessed record levels of decommissioning activity due to aging fields, sustained low oil and gas prices, and greater regulatory oversight and scrutiny." Moreover, "more than 40 percent of all decommissioning activity to date has occurred over the past decade."

"From a strategic point of view, now is a very unique opportunity for us to admit there's a problem," said Williams, the LSU engineer. Every well ever drilled will need to be plugged. With a cascade of plugging projects imminent, it is imperative now more than ever to nail down proper methodology.

One 2019 paper reviewing plug and abandonment methods found that, despite many layers of cylindrical casings and cement barriers—the industry's most-used technique for plugging, many wells still leak because of chemical stressors and the constant shifting tectonics of the Earth.

"Just because you plug a well, that doesn't mean it's plugged forever," Williams said. "It's plugged for as long as that piece of material is going to last."

It's a fallacy to think a company will clean up their mess once they no longer want to produce oil or gas, said Milliken Biven.

Evidence is mounting that the story for these wells rarely ends cleanly after plugging and abandonment.

Drilling rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. A report from this year found more than 1,300 offshore facilities were missing from government documentation. (Credit: Tara Yacovitch/Scott Herndon)

(Credit: Tara Yacovitch/Scott Herndon)

(Credit: Tara Yacovitch/Scott Herndon)

In a recent study based on marine hydroacoustic imaging of plugged wells in the North Sea, scientists found that 926 wells out of the 1,792 observed (52 percent) are likely to leak. By their estimates, these supposedly plugged wells in the central North Sea could emit anywhere from 0.9 to 3.7 kilotons of methane a year.

These supposedly plugged wells are by no means leak proof, but the way leasing, contracting, and liability happens, companies technically aren't liable for leaks post-plug and abandonment, Milliken Biven said. "Everything fails eventually, but there is no commitment on any one side to actually look at these leaks in perpetuity."

The industry could find solutions, Williams said, but huge oil and gas companies are not dedicating money into finding them, though they definitely could. "There are technological solutions out there that we could bring over and apply to this problem," he said. "But they're in other industries, they're in aerospace, they're in medicine, they're in all these other disciplines." These other industries have solved similar problems of leakage and degrading materials as far back as 30 years ago.

The barrier to finding better plugging and abandonment protocols, therefore, is not an issue of innovation, but one of willingness and initiative. And cost is a major deterrent. It's a feedback loop, Williams said: Companies don't want to address the issue due to costs, and so the problems worsen and become more expensive—and more difficult—to fix over time.

When it comes to the per-well cost of plugging, "there's huge variation," said Kang. She parsed U.S. government data to see how much they were spending on plugging—the government becomes responsible for plugging wells when operators go bankrupt and cannot shoulder their liabilities. "Not every well is the same. But the per well cost is anywhere from the high tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even more than a million." Those figures are just based on government spending. Data on corporate plug and abandonment spending is not available.

A BSEE document on Decommissioning Methodology and Cost Evaluation calculates the average cost of decommissioning an offshore well in the Gulf to be in the range of $340,000 to more than $420,000 for wells less than 400 feet deep, which is what the majority of older, soon-to-be decommissioned wells are. For a well 5,000 feet deep that could go up to almost $1.5 million.

Tara Yacovitch and her team found the top 2 percent of emitters, so-called super-emitters, leak very high levels of methane, but are largely unidentified in a literal sea of sites, (Credit: Tara Yacovitch/Scott Herndon)

BSEE platform inspection. (Credit: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement)

Wells in state waters may be all the more problematic, since they are usually older and probably did not have to adhere to modern safety and environmental standards.

"I did an estimate, just a back-of-the-envelope calculation, and I think in Louisiana it's easily a $2-5 billion-worth problem," said Williams. "And that is just Louisiana. Nationwide, it's definitely a multi-billion dollar issue."

Furthermore, Williams wants oil and gas to take a leaf out of nuclear's book: Nuclear energy producers will often think in terms of life cycle costs, taking a small percentage of energy sales and saving that money for disposing nuclear waste. The fossil fuel industry has no equivalent, he said, so by the time it is time to retire a site, "there has been no money saved by the regulator or by the government or by anybody to help with those costs of plugging and getting the areas cleaned up."

Konek added that some of the most potentially effective strategies are mostly non-technical, like incentivizing methane storage: "In certain places there's a lack of infrastructure to get gas to market, and so you have companies that are letting that go." Finding more efficient ways to store and use that gas could convince companies to keep better track of the methane gas coming from their wells.

As it stands, letting methane pool and seep means letting all that methane get to the atmosphere. "Depending on the water depths, we estimated in total, probably about a third of the gases that is emitted at the sea floor will enter the atmosphere," Matthias Haeckel, a marine geochemist and an author of the North Sea hydroacoustic imaging study, told EHN. At shallow water depths, around a hundred feet or less, all that emitted methane will get to the atmosphere in a few months, he added.

But even if methane doesn't make its way from the sea floor to the atmosphere, the act of drilling results in fractures and pathways for gas to pool and accumulate in ways that it otherwise would not, potentially creating risk of blowout events, Christoph Böttner told EHN. Böttner is a marine geoscientist at the University of Kiel and one of Haeckel's co-authors.

In their study, Böttner and Haeckel's team used hydroacoustic imaging to look at marine sediments and estimate where pools of methane lie in the ocean floor. Using this technique in tandem with existing regional seismic data, they said, could guide industry away from potentially problematic areas. Layer on satellite imaging and infrared spectroscopy, and you have a much better chance at getting an accurate idea of where gas flow exits.

Uncontrolled flow of natural gas, including methane is also a leading hazard for oil and gas workers. The Deepwater Horizon blowout event is still salient a full decade later. But measures to prevent future blowouts have actually decreased in the last decade. According to the AP, "inspections fell from 4,712 in 2013 to 3,717 in 2019," and while in 2016 the government required companies to test their blowout preventers every 14 days, "the Trump Administration allows companies to test every 21 days, saying more frequent testing would risk equipment failure."

Microbes and methane

Methane escaping the ocean floor can be a completely normal phenomenon, especially in the Gulf of Mexico, Jennifer Biddle, a biochemist at the University of Delaware, told EHN. Biddle studies natural methane seeps at or under the ocean floor and assesses how that gas affects microbiota. She said that the tectonic geography of the Gulf of Mexico makes it prone to frequent little earthquakes—combined with all the fossil fuel inside the sediments of the sea floor, the whole area is a natural methane emitter. But microbes generally eat that gas before it reaches the surface.

Microflora and microfauna thrive off of this methane, providing the base for other organisms to come and enrich the habitat ecology.

At natural seep sights, Biddle said, "a lot of estimates are that [microbes] can take up over 90 percent of the methane that is released." But when you add human activity that increases both the rate of gas going up and the number of sites gas is released from, the balance is thrown off and the microbes have a hard time keeping up, she said.

Milito, the president of the National Ocean Industries Association, said in an email that methane emissions from oil and gas activity are unlikely, and that "most data regarding methane leaks from the Gulf of Mexico actually point to natural seepage from the sea floor. Some studies estimate that there are 20,000 natural seeps in the Gulf of Mexico."

But the presence of oil in the Gulf of Mexico is very likely compounding the issue. A 2011 paper in Annual Review of Marine Science says that "the co-occurrence of oil with methane at the sea floor frequently leads to bubbles coated with oil," which prevents the methane in those bubbles from diffusing and allows more bubbles to reach the surface, intact.

"We'll go somewhere like the Gulf of California, where there's definitely gas coming out of the sea floor, but there's so much microbial activity, that you hardly ever see bubbles coming up at the surface," Biddle said."Versus in the Gulf of Mexico, the rate in some of these areas is so high that you see huge bubbles coming up to the surface. And so that's obviously the stuff that microbes aren't able to eat."

The ocean burping up pockets of gas is an indication that things are off-kilter. Given the natural presence of seepage in the Gulf of Mexico, the microbes there are probably robust enough to handle a little more methane than in other places, but unfortunately, Biddle said, we don't really know what that threshold is. In places like Finland and Canada, the governments are currently funding research to find those baseline microbial consumption abilities, she added, and those results "might change how they prepare for industrial projects." Unfortunately, the Gulf of Mexico is beyond that point.

International cooperation

Even with its poor record-keeping, the U.S. has one of the better public datasets when it comes to offshore wells,

Manfredi Caltagirone, an officer at the United Nations Environment Programme, told EHN. He added that the U.S. tends to have the most research funding—a new challenge is getting that same scientific momentum to the rest of the world.

These studies can be even more difficult to conduct overseas, especially in areas of the world where the oil and gas industry is controlled by national governments, said Chris Konek.

Under-documented methane emissions from oil and gas wells exist wherever oil and gas drilling exists. Studies everywhere from the

Bohai Sea in China to the North Sea to the Sarat Basin in Australia indicate that fugitive emissions are a global concern.

"You cannot manage what you do not measure," said Caltagirone.

The Climate & Clean Air Coalition, Environmental Defense Fund, UNEP, and the European Commission recently announced the formation of

The Oil and Gas Methane Partnership—62 companies with assets on five continents have committed to measuring and reporting methane emissions with an unprecedented level of granularity.

Methane emissions from oil and gas could potentially be much easier to get under control than emissions from other sectors, Caltagirone said. Agriculture is hugely problematic when it comes to methane—but there are about

2 million farms in the U.S, and only about 9,000 independent oil and gas producers.

Collaborating with governments and corporations alike is key, Caltagirone said, especially since it's the companies who have the technology, finance, and in-house expertise that can be put to good use. "It's really a matter of willingness," he added—a willingness, he said, that has been slow to grow because "the issue of methane emissions was a very well-kept secret until very recently."

A natural place to start is to tackle the super-emitters Yacovitch found. "The huge variability in emission rates, and the existence of super-emitters, brings up the attractive idea that if you find these few sites that are causing the larger proportion of emissions, you can have a big impact on the total emissions," Yacovitch said.

Playing catch up

Plugging and abandonment efforts right now are playing catch-up—and the past four years have not helped. During his time in office, President Trump lifted new offshore drilling bans put in place by the Obama Administration. When President-elect Joe Biden won the recent election, the Trump Administration pushed to hold a final oil and gas auction, selling leases more than half a million acres as companies jumped to scoop up land—President-elect Biden has said he will put a ban on new leases on public lands and waters. Mike Celata, Gulf of Mexico regional director for BOEM, told the Texas Tribune that the auction pulled in $121 million in high bids, exceeding the agency's target of $100 million.

Nothing short of a ban will be effective, said Milliken Biven, because of the long-lived repercussions: "A lease that happens today may not come online for another three years, and then it's going to operate for 80 years — in what world does it make sense to keep continually selling leases."

Beyond banning new leases, Caltagirone said working to mitigate methane leaks from oil and gas wells could benefit all involved. "It makes perfect sense from a climate perspective, from an economic perspective. It makes sense for the companies that are trying to push natural gas to be in the energy mix a little longer, and it makes sense for the governments because it creates jobs—I cannot think of one actor for which this doesn't make sense."

Milliken Biven agrees, which is why she has been proposing a new federal agency to Congress, the Abandoned Well Administration. This proposed agency would hire oil and gas workers to identify and geotag every single well, as well as create a process for measuring and repairing leaks.

The oil and gas sector lost more than 100,000 jobs between March and August of 2020 alone. These people could be put to work "for decades," Milliken Biven said.

"The scope and scale of this is so massive, and we need their skills right now."