How artificial intelligence can help save us from air pollution

Researchers find AI may outperform traditional models, which could give more advance warning of bad air days, and reduce harmful exposures and hospital visits.

As air quality plummets across the U.S. this summer, researchers have a glimmer of good news.

Artificial intelligence may soon provide advanced warning of future pollution events, which could help hospitals prepare for the uptick in pollution-related illnesses, or even reduce people's exposure entirely.

A spike in air pollution often leads to a spike in hospital admissions, as it can exacerbate asthma and other pre-existing respiratory conditions, cause upper respiratory tract infections, or increase the likelihood of stroke. But it's currently impossible to prepare for these spikes due to the constraints of existing air quality forecasts, which are only accurate up to three days in advance, Yunsoo Choi, associate professor of atmospheric chemistry from the University of Houston, told EHN.

In that short amount of time, one of the only things we can do to protect ourselves is to limit time spent outdoors.

Related: Measuring Houston's environmental injustice from space

But now, through the use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, Choi and the University of Houston's Air Quality Forecasting and Modeling Lab created a new model that can predict ozone pollution up to 14 days ahead of time.

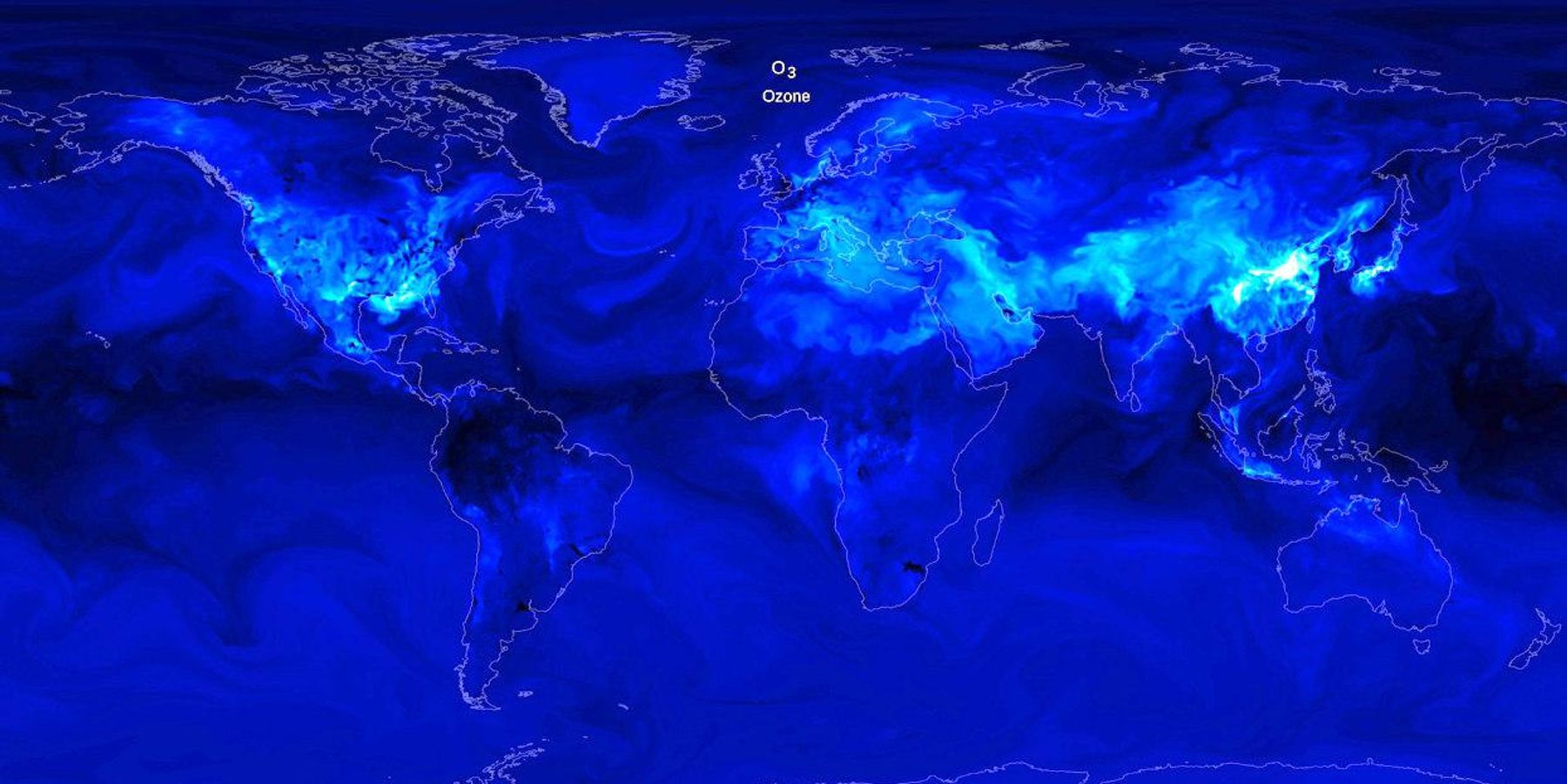

While ozone in the upper atmosphere shields us from the sun's ultraviolet radiation, ozone at ground-level is a harmful pollutant that irritates our lungs. Since it is formed in the atmosphere on hot, sunny days, we will see unprecedented spikes in ozone due to climate change, similar to what we witnessed across the U.S. during the country's most recent heat wave.

These models could give local governments more opportunities to control pollution emission sources.

"Having a model that runs faster allows [local governments] to explore a greater variety of scenarios of how they can improve [air quality]," Sherri Hunt, the Principal Associate National Program Director for the Air, Climate and Energy Research Program at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), told EHN. Hunt was not involved in this study. For example, if researchers determine the future high ozone event will be caused by cars, then policymakers can suggest ways to minimize the number of cars on the road.

In addition, with Choi's AI model, "we could decide how we're going to staff the emergency room" during bad air events, Hunt said.Artificial intelligence to improve air quality forecasting

Yunsoo Choi, left, associate professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Houston, and Ph.D. student Alqamah Sayeed developed a new model to better predict ozone levels. (University of Houston)

Traditional air quality forecasts are created by numerical models, which are essentially sophisticated calculators. They solve many lines of mathematical equations to determine how much pollution will be produced, and how it will be transported across an area at a given point in time.

These equations aren't solved only once. They have to be solved for each hour the model forecasts into the future, which takes a lot of time and computational power.

"In order to forecast two or three days...that takes a few hours" even with a supercomputer, said Choi.

AI models predict ozone without these time-consuming calculations. Instead, researchers "train" the model by providing past air quality data, which the model uses to learn how ozone behaves under different sets of meteorological conditions.

Based on the patterns observed, the model makes an educated guess of how much ozone might be present in the future. It only takes minutes and is more accurate than its predecessors.

The researchers demonstrated this by modeling ozone pollution in South Korea in 2017 after training the AI model on data collected up to three years prior. They then compared their results to the Community Multi-scale Air Quality Model (CMAQ), which is a commonly used numerical model developed by the EPA. Using CMAQ, the model's average accuracy peaked at 77% on day one of predictions and decreased rapidly over the following 14 days. When Choi used artificial intelligence, however, the average accuracy on the first day of predictions was 90%. While this value decreased trailed off over the two weeks, it still performed better than CMAQ did on day one.

Air pollution strain on hospitals

The highly accurate 14-day forecasts of Choi's AI model, combined with its faster computational time, could alleviate stress on our public health system. "We can see real increases in emergency department visits and other cardiovascular and respiratory impacts" following an air pollution event, said Hunt.

For example, one recent study that looked at Medicare patients concluded that exposure to ozone, among other pollutants, might contribute to thousands of additional hospital admissions each year.

Hospitals "have to show that there's a need if they're going to increase their number of beds or their number of providers in a particular area," explained Hunt.

Knowing how pollution levels could change two weeks in advance could help hospital administrators make their case more efficiently.

Climate change and ozone

There's also the matter of climate change, which can influence the amount of ozone produced in the atmosphere due to the uptick of hot, stagnant weather.

But it's hard to update the equations and parameters that numerical models use to calculate pollutant concentrations, said Choi, who has worked with these types of models in the past. "It's not easy to adjust to new types of [weather] phenomena" like heat waves.

On the other hand, however, AI models are much more adaptable. They learn from their mistakes and adjust their predictions accordingly. They can also be retrained with new data to improve their forecasts.

Artificial intelligence limits

Credit: Hornbeam Arts/flickr

AI technology has limitations. For one, researchers might see that the model is producing the right answer, but they "don't know if the model is getting those things right for the right reasons," said Hunt.

However, "by using [numerical modeling] we can know the all the details of what happened—what kind of chemical or physical properties are critical" in creating high pollution events, said Choi. A combination of both models will likely need to be used in the future.

It's just going to take some time. "Within EPA, I don't know anyone, any of our research scientists, who are using AI techniques," said Hunt.

The agency is, however, funding academic researchers who are focused on improving AI models and integrating them with the technology that exists today.

"Once that work is done that can potentially be brought back to the agency," said Hunt. "We want to use [models] to inform actions to make more people breathe clean air, so if we can make a better tool then that's going to benefit us in a variety of different ways."

Banner photo: While ozone in the stratosphere is critical to maintaining life on Earth, surface ozone, shown here, is a toxic gas to most plant and animal species. (Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio)