Heat is deadly—even in Montana. But the city of Missoula is doing something about it.

Missoula's forward thinking climate planning offers lessons for other cities and towns facing similar conditions.

When you think of cities impacted by the urban heat island effect, you probably think of steamy Houston or the concrete jungle of New York. Missoula, Montana probably doesn't come to mind.

But, thanks to climate change, Missoula is getting hotter, with average temperatures expected to climb 2-5 degrees Fahrenheit over the next couple of decades.

In a city where extreme heat is new and air conditioning is rare, rising temperatures can be deadly—especially for the elderly and other vulnerable groups. Worse, the city sits in a valley that collects smoke from wildfires, which are expected to get worse in a warming world. So, when residents throw open their windows to cool off, they are often assaulted by unhealthy air.

Missoula is tackling this problem head-on. The city recently partnered with scientists affiliated with the Thriving Earth Exchange, a project of the American Geophysical Union, to map heat patterns and vulnerable populations. Armed with that data, the city and its nonprofit partners are devising strategies to keep Missoula cool.

Missoula was already ahead of the curve on climate adaptation. The city formalized a farsighted Conservation and Climate Action Plan in 2013, and appointed an Energy Conservation Coordinator, Chase Jones, whose job is to "lose sleep" over implementing the plan. (Jones likes to joke that he has increased his coffee intake as a result.)

And, since 2015, a nonprofit called Climate Smart Missoula has worked with the city to reduce the community's carbon footprint and increase its resilience.

While it is still in its earliest stages, the story of Missoula's work-in-progress suggests lessons for other cities and towns facing similar conditions.

Understand the threat

It's important to know that extreme heat is the deadliest climate impact, causing at least 1,100 deaths each year in the U.S. — more than any other weather-related hazard. Heat kills directly, by heat stroke (or hyperthermia); and indirectly, by exacerbating chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and diabetes.

Cities are hardest-hit, because their expanses of concrete and asphalt absorb and hold heat. That is why air temperatures in cities can be as much as 22°F higher than in the surrounding countryside. Higher temperatures drive increased energy use, which contributes to poor air quality.

Air pollution, in turn, exacerbates asthma and other respiratory conditions.

In Missoula and elsewhere, the urban heat island effect disproportionately affects the most vulnerable, including low-income households, children and the elderly.

And higher latitudes are no guarantee of safety: in fact, the CDC reports that some of the deadliest recent heat waves have taken place in Northern cities that are ill-prepared for extreme heat.

Build partnerships to map the problem

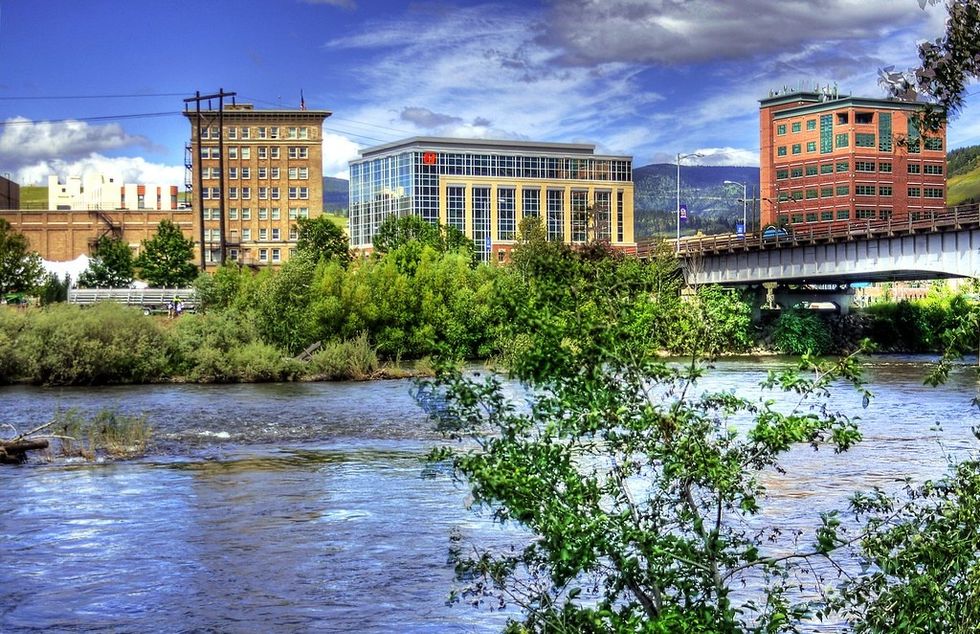

Downtown Missoula. (Credit: Micah Sheldon/flickr)

The city of Missoula and Climate Smart Missoula had already done the hard work of devising a plan to reduce carbon emissions. But adapting to excessive heat required different kinds of data and expertise. So, the city reached out to connect with the Thriving Earth Exchange (TEX).

TEX, which works to help solve environmental problems by matching communities with knowledgeable scientists and nonprofits was an instant, natural fit. "TEX really suited Missoula's situation," says Chase Jones, "because it recognizes that there is sometimes a gap in capacity and skills and resources in local governments around energy and climate change issues."

TEX connected the city with an expert right in their backyard: Anna Klene, a professor of geography at the University of Montana. Klene was joined by climatologist Nick Silverman, and then recruited graduate student Julie Tompkins to create a detailed map of Missoula's heat problem.

Layer the data

As a first step, Silverman used satellite imagery to map the city's land surface temperature. But the city wanted to add a socioeconomic component to better identify neighborhoods most at risk. "We wanted to look on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood, block-by-block basis and see where the most sensitive populations in Missoula are impacted by heat," says Julie Tompkins.

So Tompkins delved into block-level data from the Census Bureau's American Community Survey, focusing on factors – including age, income level and type of housing – that help determine susceptibility to heat impacts. Those data were layered with the heat map, showing literal hot spots and vulnerable populations.

Then, using the layered data, "I could go to those neighborhoods and see, 'There is low-income housing here. There is a mobile home court here. There is senior housing here.'" Tompkins says.

Get information to those who can put it to use

The next step was to get the mapping data "in the heads and in the work plans of those who could apply it," says Chase Jones. To that end, the team shares its findings with health officials, the City's Energy and Climate Team, planners and others.

The goal is to show how warming impacts the people of Missoula, and build that into city services and plans. For example, parks officials can use this map, together with additional research and mapping efforts, to prioritize neighborhoods for tree-planting and pocket parks, and build shade structures on exposed trails.

Health and social service agencies can initiate efforts to educate, look after, and provide resources for vulnerable residents. Planners can find ways to slow the march of concrete and asphalt.

Development agreements can incentivize cooling strategies such as light-colored roofs and shade features, while preserving the urban forest and integrating green infrastructure.

Much of that work is already under way in Missoula, says Jones. But the new data "emboldens them to do even more of the good work they're doing," he says, "so that we break up that concrete; we have cool, shady places; and everyone can access it no matter what their income level or health situation."

The heat data are also advancing a conversation about the mental health impacts of climate change, says Amy Cilimburg, Director of Climate Smart Missoula.

For example, rising temperatures are linked to an increase in domestic violence. "That means that police and first responders need to find ways to cool down the temperature as well as the situation," says Cilimburg, "because people are not at their best when they are hot."

A holistic approach

The city of Missoula and its nonprofit partners are beginning to use multilayered data to consider how rising temperatures connect to a broad range of problems, from asthma to violence. Linked problems require holistic solutions: "You can't look at heat impacts in isolation," says Cilimburg, "A cross-sector approach will get you farther as a community."

That approach is bearing fruit in Missoula, where extreme heat is becoming part of the conversation on public health, housing, development, parks and more. In this way, Missoula is "mainstreaming" climate adaptation.

"It's a way to build capacity, understanding and innovation that's better than building your own little silo around climate," says Jones. He adds that, "Intentional integration into existing agency, systems, planning and community is an approach that we hope results in broader change and more expansive impact."

There are practical benefits to this holistic approach. Because, just as the problems compound one another – as when extreme heat worsens air quality – the solutions can have positive synergistic effects. For example, cooling the city with shade trees and light roofs will result in lower energy use and reduced greenhouse gas emissions—a win for mitigation.

Those efforts will also improve air quality and reduce health impacts.

And the biggest beneficiaries of those positive changes are the city's most vulnerable people: low-income families that can't afford air conditioning; people with chronic health conditions; children and the elderly.

That's a win for equity, says Jones. And for resilience, because "in the end, our city is only as strong as its most-vulnerable residents."

Laurie Mazur is the editor of the Island Press Urban Resilience Project, which is supported by The Kresge Foundation and The JPB Foundation.