"Off the charts" arsenic levels detected in Western Pennsylvania groundwater

The pollutant is leaching from a coal ash landfill at a power generating station

PITTSBURGH—New data shows arsenic at levels 372 times greater than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's threshold for safety in groundwater an hour northwest of Pittsburgh.

The cancer-causing pollutant is leaching from a former coal ash landfill at the New Castle Generating Station, according to a new report. Of the 265 power plants throughout the U.S. that are investigated in the report, New Castle Generating Station ranked number five of the 10 most contaminated sites.

The study, conducted by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice, used industry-reported data from more than 4,600 groundwater monitoring wells located around the ash dumps of 265 coal-fired power plants, or roughly three quarters of all coal plants in the country. Of those sites, 91 percent were contaminated with unsafe levels of toxic contaminants like the ones found at the New Castle site.

The data became public for the first time in 2018 because of requirements in federal coal ash regulations issued by the Obama administration in 2015. The remaining plants not included in the report either closed their ash dumps before 2015 or were eligible for an extension.

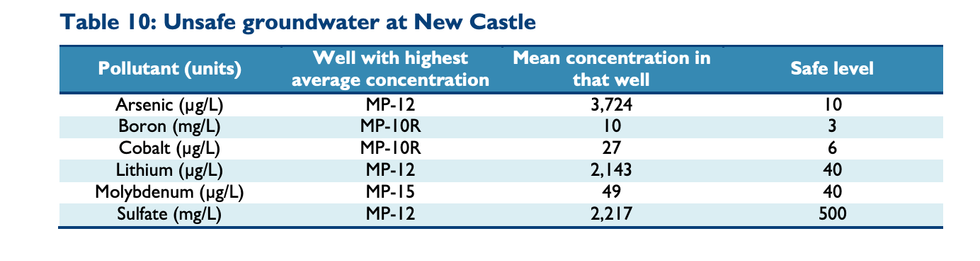

The researchers discovered arsenic levels of 3,724 micrograms per liter in groundwater at the New Castle Generating Station site—enough to cause cancer in one out of six people exposed to that level of the pollutant. The EPA's maximum contaminant level used under the Safe Drinking Water Act is 10 micrograms per liter.

Exposure to arsenic can cause leukemia and lymphoma, cancer of the skin, stomach, and kidneys, and result in lower IQs in children.

"That level of arsenic is so hazardous it's just off the charts," Abel Russ, an attorney for the Environmental Integrity Project and co-author of the report, told EHN. "Drinking even 10 micrograms per liter of arsenic is still not safe. The EPA set that limit because it wouldn't be practical to ask utilities to go lower, but cancer risk at 10 micrograms per liter is still unacceptable to most public health officials."

Public drinking water must be tested to ensure it contains fewer than 10 micrograms per liter, but testing is not required for private wells. These levels of arsenic in the groundwater could mean the contaminant is making its way into private wells, rivers, and streams in the region. The area surrounding the site is largely rural, so many residents are reliant on private wells.

New Castle Generating Station was previously a coal-fired power station, which was converted to natural gas in 2016. The new report states that the plant is owned by NRG Energy, but a spokesperson for NRG told EHN the site has been owned and operated by GenOn Energy (previously known as Reliant Energy) since December 2018. GenOn was acquired by NRG in 2012, but later transitioned back into a standalone company. A spokesperson for GenOn did not return EHN's requests for comment.

Data also showed boron, cobalt, lithium and molybdenum in groundwater at the site at levels exceeding safety thresholds. Boron exposure has been linked to reproductive health issues in animals. Lithium exposure can cause damage to the kidneys, while cobalt exposure is linked to cancer and thyroid disorders, and molybdenum exposure has been linked to joint issues.

"These are the pollutants most prevalently associated with coal ash," Russ said. The report found that coal ash is leaching into groundwater near at least nine other power plants throughout Pennsylvania, and over 200 sites throughout the U.S.

"The New Castle Generating Station is basically a poster child for what can happen at these sites," he added.

New legislation introduced in 2015 requires utilities to store coal ash in lined landfills or ponds, but most facilities are using storage sites built before those rules took effect. And last year, the Trump administration began rolling back parts of the 2015 coal ash rule, making it easier for facilities to skirt regulations.

"The findings of this report are disturbing, but unfortunately not surprising," said Jennifer Peters, National Water Programs Director for Clean Water Action, in a statement. "For decades, coal utilities have been dumping their toxic waste in primitive pits—often unlined, unstable, and near groundwater—while state and federal regulators have mostly looked the other way. These dangerous coal ash ponds should have been closed and cleaned up years ago."

To protect residents, Russ said, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, which regulates water pollution, should make sure they know where all the coal ash ponds and landfills in the state are located, since any that closed prior to the 2015 regulations aren't required to conduct groundwater testing. In locations where coal ash is in contact with groundwater, the sites must be excavated to stop contaminants like arsenic from leaching before monitoring can begin to ensure that the groundwater near the sites remains clean.

Neil Shader, a spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, said the agency is reviewing the new report's findings.

He added that "Pennsylvania's residual waste regulations are, in most cases, more stringent than EPA's coal ash rules," and noted that public water systems are required to remove contaminants such as arsenic.

Russ, however, had advice for homeowners near the site on private wells: "Familiarize yourself with what pollutants have been found at the site, then test your well water for all of those pollutants.

"If it looks good, don't worry. Wait a few years and then test again. If it looks bad, call a lawyer."