Chemical recycling has an economic and environmental injustice problem: Report

“It wouldn’t even make a dent in the amount of plastic pollution out there.”

PITTSBURGH — Chemical recycling projects are unlikely to generate local economic benefits or help reduce global plastic pollution, according to a new report.

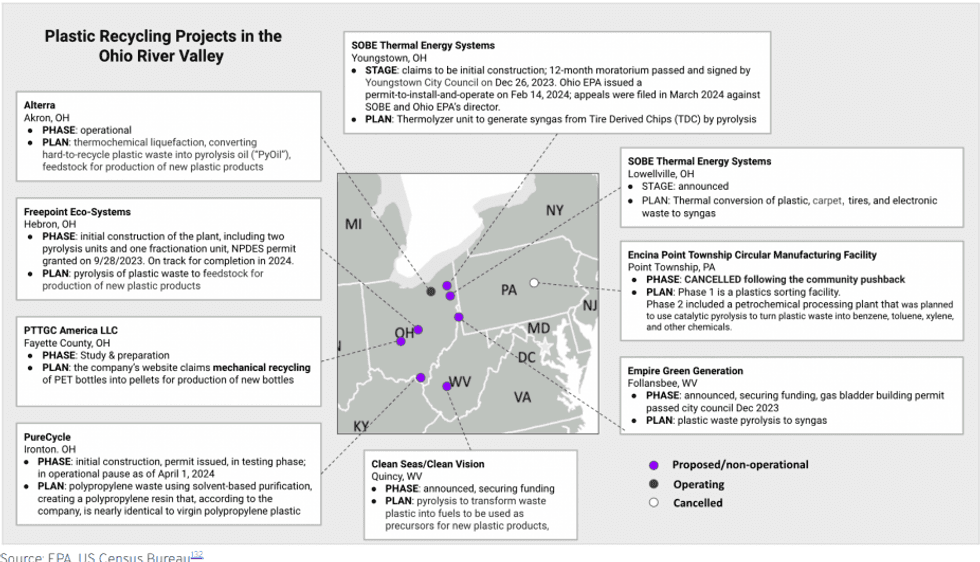

The report, published by the progressive think tank Ohio River Valley Institute, investigated the technological and economic challenges associated with chemical recycling, with a focus on the Ohio River Valley, which spans western Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

“There’s a tendency to co-locate these facilities where there’s already a petrochemical cluster of some sort, which means communities already burdened by petrochemical industries, such as Ohio River Valley, become even more polluted,” Kathy Hipple, one of the report’s authors, told EHN.

Chemical recycling, sometimes referred to as advanced or molecular recycling, refers to processes that use heat, chemicals or both to break down plastic waste into component parts for reuse as plastic feedstocks or as fuel. These processes are different from conventional or mechanical plastic recycling, which breaks down plastic waste physically but not at a molecular level.

Only 5% to 6% of plastic waste gets recycled in the U.S., and the proponents of chemical recycling say the industry could help change that.

“We’re not going to create circularity for plastics with one single solution,” Chris Layton, director of sustainability for specialty plastics at Eastman Chemical Company, told EHN. “We’re going to have to eliminate some plastics we really don't need, figure out ways to reduce and reuse and maximize what we can do for mechanical and advanced recycling.”

But environmental and health advocates say the process is still inefficient, energy intensive and emits hazardous chemicals into the air and water. As much as 80% of plastic waste put into chemical recycling processes is lost as hazardous emissions, according to a report by the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) and Beyond Plastics.

The Ohio River Valley Institute’s report concluded that chemical recycling only converts 15%-20% of plastic waste into recycled plastic products (the rest become emissions, fuel or hazardous waste), that none of the chemical recycling plants currently operating in the U.S. are commercially successful, that chemical recycling is technically and financially risky and that the chemical recycling process is toxic and poses health and safety risks to workers and communities — particularly those that are already overburdened by pollution from the petrochemical industry.

“Going into writing this report, I thought maybe chemical recycling was a good solution to the global plastic pollution problem,” Hipple said. “Unfortunately, it turns out that chemical recycling is not the solution — it wouldn’t even make a dent in the amount of plastic pollution out there.”

There are 10 functional chemical recycling facilities in the U.S., according to the report, two of which are in the Ohio River Valley (Alterra and Purecycle, both of which are in Ohio). Most are still operating in pilot phases, according to the report, processing only small amounts of plastic, because chemical recycling is expensive and it’s still cheaper to buy virgin plastic and fossil fuels.

“Unfortunately, it turns out that chemical recycling is not the solution — it wouldn’t even make a dent in the amount of plastic pollution out there.” - Kathy Hipple, report author

As an example of the industry’s financial challenges, Hipple noted that Shell, which operates a large petrochemical plant in the Ohio River Valley, recently conceded that it would abandon its pledge to turn more than 1 million tons into oil per year by 2025 because the plan is “unfeasible.”

“If a company like Shell is backing away from its pledge to increase advanced recycling when they have some of the biggest capital expenditure budgets in the world, that really demonstrates that this technology is immature and there’s no business case for doing this at the moment,” Hipple said.

Despite these challenges, at least nine chemical recycling plants have been proposed throughout the Ohio River Valley, including now-canceled or on-hold projects in Youngstown, Ohio and Point Township, Pennsylvania. Other plants proposed in the region have faced stark community opposition.

Environmental justice concerns

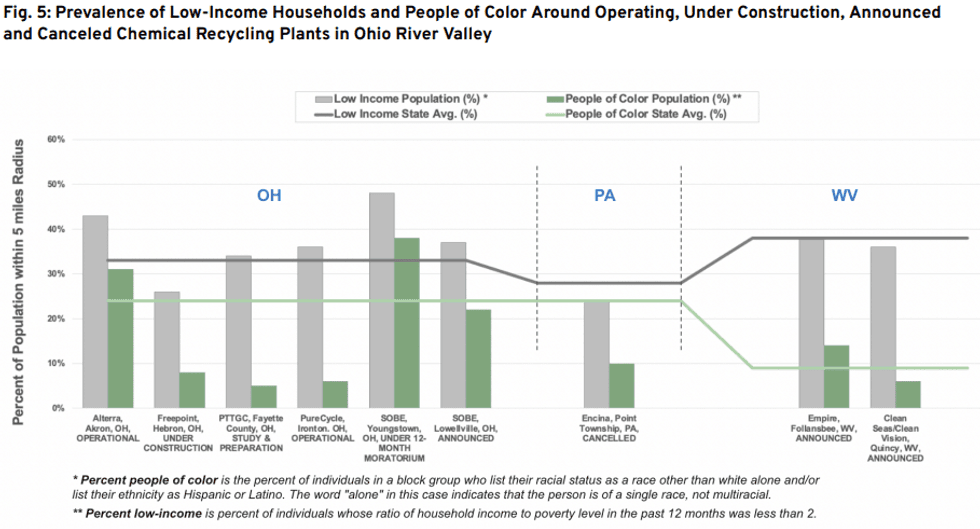

At the national level, 70% of constructed chemical recycling plants are located

in low-income areas and 60% in neighborhoods of color, according to Beyond Plastics, prompting concerns about environmental injustice.

The new report adds to these concerns, as it found that six of the nine chemical recycling facilities proposed in the region would be located in environmental justice communities with a higher percentage of low-income households than the state average. Three would be located in neighborhoods predominantly populated by people of color.

“These communities are already overburdened by pollution and the emissions from chemical recycling facilities are highly polluting and highly toxic,” Hipple said.

Credit: "Chemical Recycling: A False Promise for the Ohio River Valley"

A database compiled in March revealed that more than 16,000 chemicals are used in plastics production, with thousands of them being toxic even in very small quantities. Many of these chemicals are released into air or water during the chemical recycling process.

“These industries often promise jobs and economic growth that never materialize for local communities,” Hipple said. “It isn’t fair that these communities wind up bearing the environmental and health costs.”