The year the West was burning: How the 2020 wildfire season got so extreme

If 2020 has proved anything, it is to expect the unexpected.

More than 4 million acres of California went up in flames in 2020 – about 4 percent of the state's land area and more than double its previous wildfire record.

Five of the state's six largest fires on record were burning this year.

In Colorado, the Pine Gulch fire broke the record for that state's largest wildfire, only to be surpassed by two larger blazes, the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires.

Oregon saw one of the most destructive fire seasons in its recorded history, with more than 4,000 homes destroyed.

What caused the 2020 fire season to become so extreme?

Fires thrive on three elements: heat, dryness and wind. The 2020 season was dry, but the Western U.S. has seen worse droughts in the recent decade. It had several record-breaking heat waves, but the fires did not necessarily follow the locations with the highest temperatures.

What 2020 did have was heat and dryness hitting simultaneously. When even a moderate drought and heat wave hit a region at the same time, along with wind to fan the flames, it becomes a powerful force that can fuel megafires.

That's what we've been seeing in California, Colorado and Oregon this year. Research shows it's happening more often with higher intensity, and affecting ever-increasing areas.

Climate change intensified dry-hot extremes

We are scientists and engineers who study climate extremes, including wildfires. Our research shows that the probability of a drought and heat wave occurring at the same time in the U.S. has increased significantly over the past century.

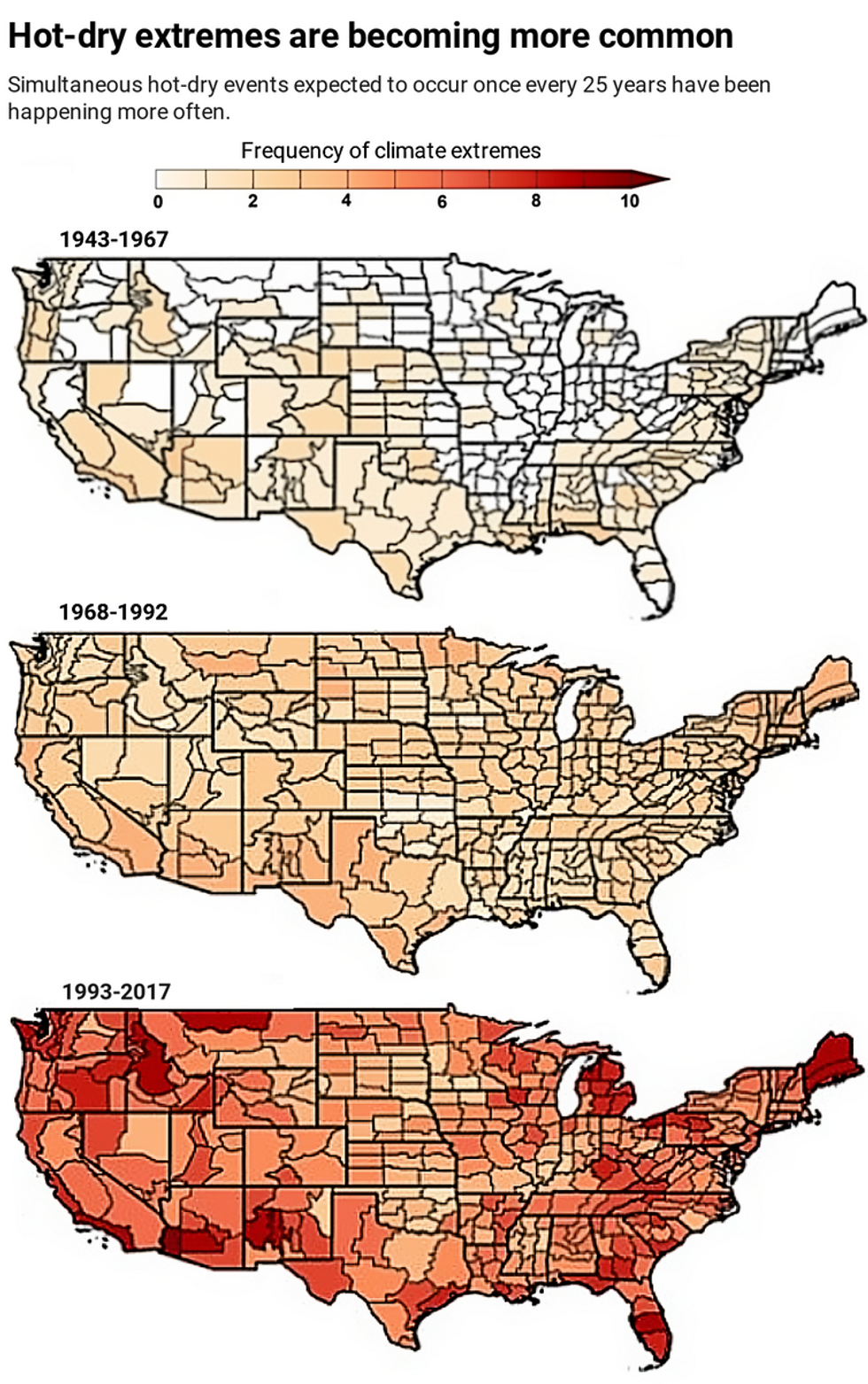

The kind of dry and hot conditions that would have been expected to occur only once every 25 years on average have occurred five to 10 times in several regions of the U.S. over the past quarter-century. Even more alarming, we found that extreme dry-hot conditions that would have been expected only once every 75 years have occurred three to six times in many areas over the same period.

We also found that what triggers these simultaneous extremes appears to be changing.

During the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, the lack of rainfall allowed the air to become hotter, and that process fueled simultaneous dry and hot conditions. Today, excess heat is a larger driver of dry-hot conditions than lack of rain.

This has important implications for the future of dry-hot extremes.

Warmer air can hold more moisture, so as global temperatures rise, evaporation can suck more water from plants and soil, leading to drier conditions. Higher temperatures and drier conditions mean vegetation is more combustible. A study in 2016 calculated that the excess heat from human-caused climate change was responsible for nearly doubling the amount of Western U.S. forest that burned between 1979 and 2015.

Worryingly, we have also found that these dry-hot wildfire-fueling conditions can feed on one another and spread downwind.

When soil moisture is low, more solar radiation will turn into sensible heat – heat you can feel. That heat evaporates more water and further dries the environment. This cycle continues until a large-scale weather pattern breaks it. The heat can also trigger the same feedback loop in a neighboring region, extending the dry-hot conditions and raising the probability of dry-hot extremes across broad stretches of the country.

All of this translates into higher wildfire risk for the Western U.S.

In Southern California, for example, we found that the number of dry-hot-windy days has increased at a greater rate than dry, hot or windy days individually over the past four decades, tripling the number of megafire danger days in the region.

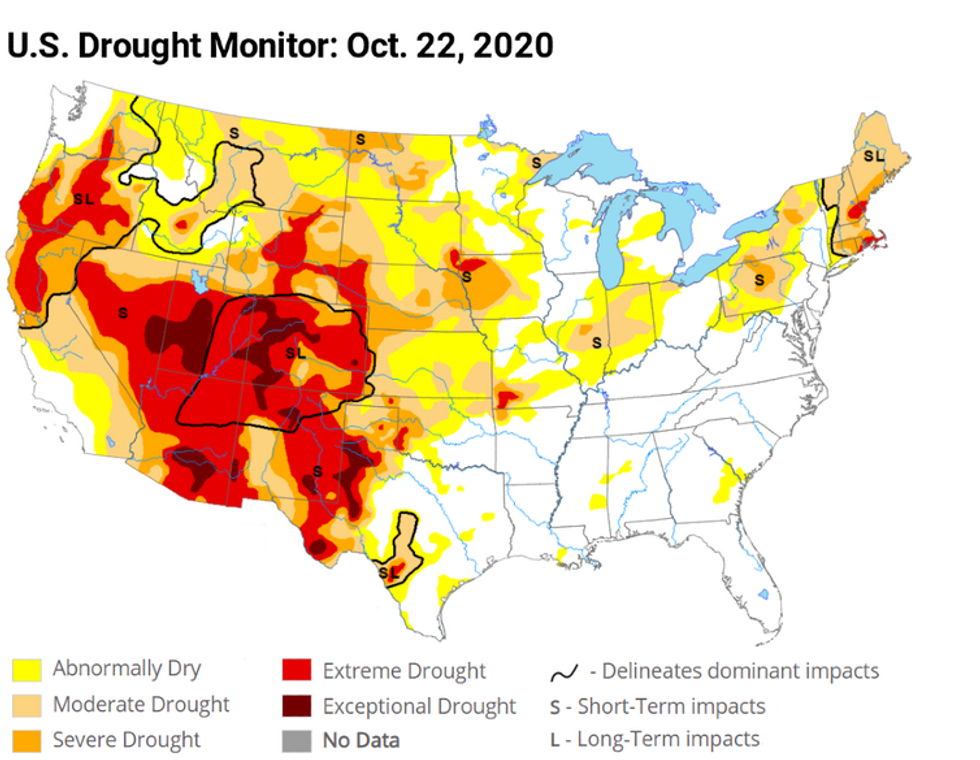

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (Credit: NDMC)

2020 wasn’t normal, but what is normal?

If 2020 has proved anything, it is to expect the unexpected.

Before this year, Colorado had not recorded a fire of over 10,000 acres starting in October. This year, the East Troublesome fire grew from about 20,000 acres to over 100,000 acres in less than 24 hours on Oct. 21, and it was nearly 200,000 acres by the time a snowstorm stopped its advance. Instead of going skiing, hundreds of Coloradans evacuated their homes and nervously watched whether that fire would merge with another giant blaze.

This is not "the new normal" – it's the new abnormal. In a warming climate, looking at what happened in the past no longer offers a sense of what to expect in the future.

"The growth that you see on this fire is unheard of," Grand County Sheriff Brett Schroetlin said of the East Troublesome fire on Oct. 22. "We plan for the worst. This is the worst of the worst of the worst."

Credit: Alizadeh, et al, Science Advances 2020

There are other drivers of the rise in fire damage, as well. More people moving into wildland areas means there are more cars and power lines and other potential ignition sources. Historical efforts to control fires have also meant more undergrowth in areas that would have naturally burned periodically in smaller fires.

The question now is how to manage this "new abnormal" in the face of a warming climate.

In the U.S., one in three houses are built in the wildland-urban interface. Development plans, construction techniques and building codes can do more to account for wildfire risks, including avoiding flammable materials and potential sources of sparks. Importantly, citizens and policymakers need to tackle the problem at its root: That includes cutting the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet.

Mojtaba Sadegh is an assistant professor of Civil Engineering at Boise State University; Ata Akbari Asanjan is a research scientist at the Ames Research Center, NASA; Mohammad Reza Alizadeh is a Ph.D. student at McGill University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Banner photo: California National Guard fighting a wildfire in September. (Credit: The National Guard/flickr)